Business Removing

Doing Business in 2005 -- Removing Obstacles to Growth

Doing Business in 2005 -- Removing Obstacles to Growth

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

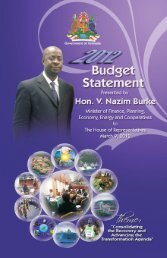

PROTECTING INVESTORS 53<br />

FIGURE 7.4<br />

Pyramid structures can mask related-party transactions<br />

Controlling<br />

family<br />

1b<br />

51%<br />

51%<br />

Choten<br />

2b<br />

Public<br />

investors<br />

Ichi<br />

Ni<br />

1b<br />

1b<br />

51% 51% 51%<br />

51%<br />

Futatsu-Ichi Futatsu-Ni Futatsu-San Futatsu-Yon<br />

1b 1b 1b 1b<br />

Source: Aikawa (1934).<br />

51%<br />

Total public<br />

investment<br />

4b<br />

takes Choten public and raises almost an additional ¥1<br />

billion. It then organizes 2 other businesses, Ichi and Ni,<br />

each financed with ¥500 million from Choten and almost<br />

¥500 million in public equity. Another 4 firms are<br />

organized under Ichi and Ni with the same strategy (figure<br />

7.4). Now the family fully controls 7 firms, with ¥5<br />

billion in consolidated assets, by leveraging ¥4 billion<br />

from small investors. To raise the same equity through<br />

Choten alone, their ownership would have been diluted<br />

to a minority 20%. Good for the family. But minority investors<br />

are more vulnerable to expropriation if they are<br />

unaware of how business between Choten and its subsidiaries<br />

could benefit the controlling family.<br />

Beneficial ownership. A third way to gain control is<br />

through nominee accounts, trust funds, or brokerage<br />

firms, where the identity of the buyer is not disclosed. 18<br />

This practice is so popular in Indonesia, that by 1996<br />

the Suharto family managed to amass control of 417<br />

companies, 21 of them publicly-listed, using nominee<br />

accounts and trusts. The practice is still permitted. In<br />

contrast, Malaysia revised its regulation in 2001 to limit<br />

nominee ownership.<br />

Voting agreements. Fourth, shareholders may have<br />

agreements that stipulate collective voting on strategic<br />

issues or managerial appointments. If these agreements<br />

are not disclosed, as in Jordan, the Philippines or Turkey,<br />

small investors may lose out.<br />

In addition to ownership disclosure, 2 types of financial<br />

disclosure help investors.<br />

Audit committees. The quality of financial information<br />

is increased if the company law or securities law<br />

requires internal audits before financial statements are<br />

released to investors. The business can have an audit<br />

committee that reviews and certifies financial data. Better<br />

yet, the committee may include some outside members.<br />

Korea has made the most progress, by mandating<br />

audit committees and also requiring that two-thirds of<br />

the committee members in large companies be outsiders.<br />

External audits. Laws can also require that an external<br />

auditor be appointed. Countries like Argentina and<br />

Spain have both an internal audit committee and an external<br />

auditor, while Hungary, like many other countries,<br />

has a requirement only for an external auditor. One<br />

caveat: in many countries external auditors are not so independent.<br />

In Peru, for example, an estimated 6,000 auditors<br />

vie for the business of 200 listed companies, which<br />

pay the highest fees for auditing services. Sometimes, the<br />

most malleable auditors get the job.<br />

Public access to information. Finally, disclosure is<br />

most effective when both ownership and financial information<br />

are available to all current and potential investors,<br />

either in stock exchange bulletins if the company<br />

is public, or in annual reports, newspapers, or company<br />

registries for privately held companies. One example. In<br />

2000 the Australian Stock Exchange introduced a realtime<br />

disclosure system that utilizes the Internet for reporting<br />

information that may affect investors’ choices. It<br />

also monitors the media for company announcements<br />

that may have not been reported but fall under the disclosure<br />

regulation. About 300 such announcements were<br />

detected last year. Yet in countries like Saudi Arabia or<br />

Venezuela, only the regulators have access to ownership<br />

information.<br />

The 7 ways of enhancing disclosure—by reporting<br />

family, indirect, and beneficial ownership, and on voting<br />

agreements between shareholders, by requiring audit<br />

committees of the board of directors and the use of<br />

external auditors, and by making such information<br />

available to all current and potential investors—make up<br />

the Doing <strong>Business</strong> indicator of disclosure (table 7.3).<br />

Twenty four countries have 6 or more of these features.<br />

Thirty others—almost all poor countries—have fewer<br />

than two.<br />

Legal protections<br />

Disclosure of ownership and financial information is<br />

just the beginning. Legal protections of the rights of<br />

small investors are needed. In the Peronnet case, for example,<br />

failure to disclose was not sufficient to void the<br />

lease agreement with SCI. The court ruled that the decision<br />

to lease was not taken with the sole intention of<br />

benefiting the majority shareholder and served a legitimate<br />

business purpose. It took no interest in the question<br />

of whether the creation of SCI and the price it