1859 Summer 2009

1859 Summer 2009

1859 Summer 2009

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

“The Tribes have been the biggest loser<br />

in the basin for 150 years,” says James Honey,<br />

a Klamath Basin program director with Sustainable<br />

Northwest, a nonprofit involved in<br />

negotiating a settlement agreement with the<br />

Tribes over water rights in the Klamath Basin.<br />

“We need to provide new economic opportunities<br />

for tribal and rural people.”<br />

a model for the West<br />

THE SITUATION IS FAMILIAR THROUGHOUT THE WESTERN<br />

United States where boarded-up sawmills or those left idle during the<br />

recent economic downturn are found near vast swaths of public lands<br />

on which overgrown forests have become vulnerable to wildfires and<br />

disease. Fire spreads quickly in the underbrush and up into the midsized<br />

trees, which act as a ladder that spreads the fire into the highest<br />

level of the canopy and grills the most mature trees. By removing<br />

the smaller trees and some of the undergrowth leftover from logging<br />

– known as “slash” – forest managers can help prevent catastrophic<br />

wildfires and restore healthy tree growth. The Forest Service, however,<br />

doesn’t have the budget to restore all federal forestland, and there’s simply<br />

no financial gain to harvesting the small-diameter wood.<br />

“We’ve got forest slums on our hands,” says David Sjoding, a renewable<br />

resources specialist with the Washington State University Extension<br />

Energy Program, a group working with Northwest Congressional<br />

leaders to develop forest management plans that incorporate tree thinning<br />

for renewable energy development.<br />

Biomass produced on forest lands in the western U.S. has the potential<br />

to generate some 2,230 megawatts of renewable energy, or about<br />

the equivalent of the energy produced by four typical coal-fired power<br />

plants, according to the Western Governors’ Association. Biomass is<br />

essentially solar energy stored in plants. It is burned to heat water to<br />

create steam that then drives a turbine and generates electricity that<br />

can be used on site or sold to utilities. The excess heat can also supplant<br />

coal and natural gas in wood products manufacturing, such as paper<br />

mills and pulp, in a process called cogeneration. Generating power from<br />

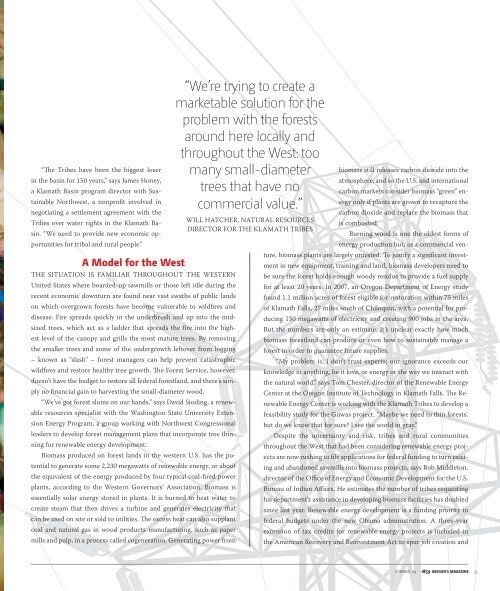

“We’re trying to create a<br />

marketable solution for the<br />

problem with the forests<br />

around here locally and<br />

throughout the West: too<br />

many small-diameter<br />

trees that have no<br />

commercial value.”<br />

WILL HATCHER, NATURAL RESOURCES<br />

DIRECTOR FOR THE KLAMATH TRIBES<br />

biomass still releases carbon dioxide into the<br />

atmosphere, and so the U.S. and international<br />

carbon markets consider biomass “green” energy<br />

only if plants are grown to recapture the<br />

carbon dioxide and replace the biomass that<br />

is combusted.<br />

Burning wood is one the oldest forms of<br />

energy production but, as a commercial venture,<br />

biomass plants are largely untested. To justify a significant investment<br />

in new equipment, training and land, biomass developers need to<br />

be sure the forest holds enough woody residue to provide a fuel supply<br />

for at least 20 years. In 2007, an Oregon Department of Energy study<br />

found 1.1 million acres of forest eligible for restoration within 75 miles<br />

of Klamath Falls, 27 miles south of Chiloquin, with a potential for producing<br />

150 megawatts of electricity and creating 900 jobs in the area.<br />

But the numbers are only an estimate. It’s unclear exactly how much<br />

biomass forestland can produce or even how to sustainably manage a<br />

forest in order to guarantee future supplies.<br />

“My problem is, I don’t trust experts; our ignorance exceeds our<br />

knowledge in anything, be it love, or energy or the way we interact with<br />

the natural world,” says Tom Chester, director of the Renewable Energy<br />

Center at the Oregon Institute of Technology in Klamath Falls. The Renewable<br />

Energy Center is working with the Klamath Tribes to develop a<br />

feasibility study for the Giiwas project. “Maybe we need to thin forests,<br />

but do we know that for sure? I see the world in gray.”<br />

Despite the uncertainty and risk, tribes and rural communities<br />

throughout the West that had been considering renewable energy projects<br />

are now rushing to file applications for federal funding to turn existing<br />

and abandoned sawmills into biomass projects, says Bob Middleton,<br />

director of the Office of Energy and Economic Development for the U.S.<br />

Bureau of Indian Affairs. He estimates the number of tribes requesting<br />

his department’s assistance in developing biomass facilities has doubled<br />

since last year. Renewable energy development is a funding priority in<br />

federal budgets under the new Obama administration. A three-year<br />

extension of tax credits for renewable energy projects is included in<br />

the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act to spur job creation and<br />

summer 09 <strong>1859</strong> oregon's magazine 35