Historic Philadelphia

An illustrated history of the city of Philadelphia, paired with the histories of companies, families and organizations that make the region great.

An illustrated history of the city of Philadelphia, paired with the histories of companies, families and organizations that make the region great.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Stotesbury, president of the Fairmount Park<br />

Commission, to facilitate construction of the<br />

proposed <strong>Philadelphia</strong> Museum of Art by<br />

shaking loose three thousand tons of rock<br />

from the hillside and, perhaps more difficult,<br />

shaking loose a $2 million appropriation from<br />

the councilmen watching the detonation.<br />

Work had started in 1919 on a design by<br />

architects C. L. Borie, Jr., C. C. Zantzinger,<br />

and Horace Trumbauer. Early estimates<br />

placed the cost at $3 million. The museum’s<br />

walls rose through 1921, and so did the price.<br />

There were accusations of graft and favoritism<br />

in contracts, and the age-old lamentation that<br />

the money could better be spent on schools,<br />

housing or health care. By 1925 the price tag<br />

was nudging $15 million. The Park<br />

Commission voted to stop spending, abandoning<br />

many planned embellishments.<br />

On the last day of 1921, Senator Boies<br />

Penrose died in his specially reinforced oversize<br />

bed in his apartment in the swank Wardman<br />

Park Hotel in Washington. He had been ill since<br />

1919. In 1920, in his house on Spruce Street,<br />

he had lain wheezing in his giant bed, with a<br />

direct phone line and a private bedside<br />

telegraph line and operator connecting him<br />

with the Republican Convention in Chicago as<br />

he maneuvered to nominate Warren G. Harding<br />

for president. <strong>Philadelphia</strong> reporters knew of<br />

Harding’s selection before the press corps at<br />

the convention.<br />

Mayor W. Freeland Kendrick looked for a<br />

tough police commander to crack down on<br />

Prohibition lawlessness. In 1924 Kendrick convinced<br />

the Marine Corps to lend him, on a two<br />

year leave of absence, Major General Smedley<br />

Darlington Butler, forty-three, a <strong>Philadelphia</strong><br />

fighting Quaker noted for brash speech and<br />

action. He had won the Medal of Honor twice.<br />

Most of <strong>Philadelphia</strong> winked at laws against<br />

drinking, but Butler would broach neither winking<br />

nor drinking. He raided speakeasies and<br />

other social venues with no regard for political<br />

sensibilities. Arrests for conducting speakeasies<br />

in September 1923, totaled fifty-seven. In<br />

September 1925, at the end of Butler’s tenure,<br />

there were 1,081 such arrests. The fact that the<br />

thousand arrests resulted in only two convictions<br />

didn’t bother Butler. He just kept raiding. “I give<br />

’em hell and make ’em like it,” he chortled.<br />

Butler remained a popular figure in the city<br />

after his controversial reign ended. In 1931, in<br />

a <strong>Philadelphia</strong> radio interview, he used the<br />

word “hell” and the station manager cut the<br />

program off the air. The incident attracted<br />

amused nationwide attention, and a Baltimore<br />

radio station invited Butler to do a broadcast<br />

there in which he would be permitted up to six<br />

hells and six damns. The affair grew into a<br />

legend, with people believing that Butler was<br />

regularly being censored by Philly broadcasters<br />

for uncontrolled cussing. A few months before<br />

he died at the <strong>Philadelphia</strong> Naval Hospital in<br />

1940, Butler arose to speak at a Salvation Army<br />

luncheon, pointed suspiciously at the<br />

microphone, and said, “You’ve got to be careful.<br />

These things misquote you.”<br />

THE SOGGY SESQUI<br />

Soon would be the moment for some civic<br />

hoopla again: 1926, the 150th anniversary of<br />

the Declaration of Independence, the Sesqui-<br />

Centennial. John Wanamaker proposed an<br />

exposition. The Vares pushed for use of their<br />

✧<br />

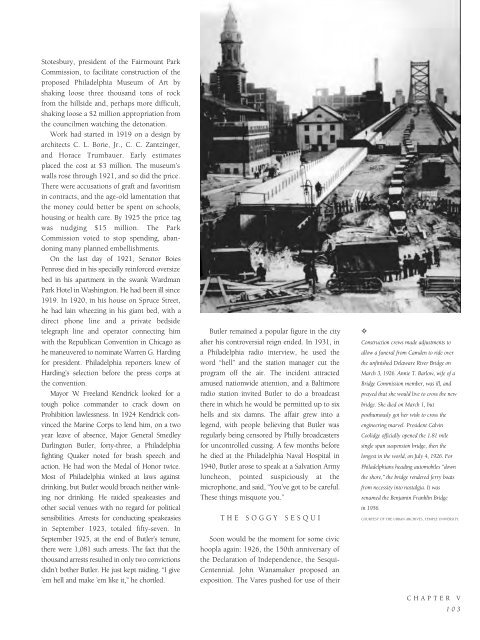

Construction crews made adjustments to<br />

allow a funeral from Camden to ride over<br />

the unfinished Delaware River Bridge on<br />

March 3, 1926. Annie T. Barlow, wife of a<br />

Bridge Commission member, was ill, and<br />

prayed that she would live to cross the new<br />

bridge. She died on March 1, but<br />

posthumously got her wish to cross the<br />

engineering marvel. President Calvin<br />

Coolidge officially opened the 1.81 mile<br />

single span suspension bridge, then the<br />

longest in the world, on July 4, 1926. For<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong>ns heading automobiles “down<br />

the shore,” the bridge rendered ferry boats<br />

from necessity into nostalgia. It was<br />

renamed the Benjamin Franklin Bridge<br />

in 1956.<br />

COURTESY OF THE URBAN ARCHIVES, TEMPLE UNIVERSITY.<br />

CHAPTER V<br />

103