Historic Philadelphia

An illustrated history of the city of Philadelphia, paired with the histories of companies, families and organizations that make the region great.

An illustrated history of the city of Philadelphia, paired with the histories of companies, families and organizations that make the region great.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

The city began developing the abandoned<br />

Hog Island shipyard as an airport. Mayor Wilson<br />

named it the S. Davis Wilson Airport. Upon his<br />

death in August 1937, it was unnamed by the<br />

council. George Connell became acting mayor,<br />

but did little acting, and January 1938 opened<br />

with Robert E. Lamberton the elected mayor.<br />

Colonel James Elverson, second generation<br />

publisher of the <strong>Philadelphia</strong> Inquirer, died five<br />

months before the newspaper’s hundredth<br />

birthday, in 1929, in his apartment in the<br />

gleaming white tower of the building he had<br />

erected in 1925 at Broad and Spring Garden.<br />

A newcomer to <strong>Philadelphia</strong> bought the<br />

Inquirer from the Elverson heirs in 1936. He<br />

was Moses L. Annenberg, who had<br />

newspapered in Chicago, Milwaukee, and<br />

New York, and was making big money<br />

publishing Racing Form and other gamblingoriented<br />

periodicals. He had just sold his<br />

Miami Tribune to Ohio publisher John S.<br />

Knight, who had recently bought the Miami<br />

Herald. Annenberg began livening up the<br />

formerly stodgy Inquirer. With him to Philly<br />

came his quiet twenty-eight-year-old son,<br />

Walter; no one suspected then that the lad<br />

would become one of America’s richest men.<br />

A little-noticed phenomenon in 1933 was<br />

government approval of twenty-eight experimental<br />

television frequencies around the nation.<br />

One was assigned to the <strong>Philadelphia</strong> Storage<br />

Battery Company, another to RCA Victor<br />

Corporation in Camden. Some engineers had<br />

primitive TV sets in their homes to receive test<br />

broadcasts. In 1936, invited journalists and<br />

other guests in Philco’s chief engineer’s basement<br />

in Rydal saw transmissions from the C and<br />

Allegheny plant, including two stenographers<br />

singing a duet and two male employees boxing.<br />

Some University of Pennsylvania home football<br />

games were telecast.<br />

✧<br />

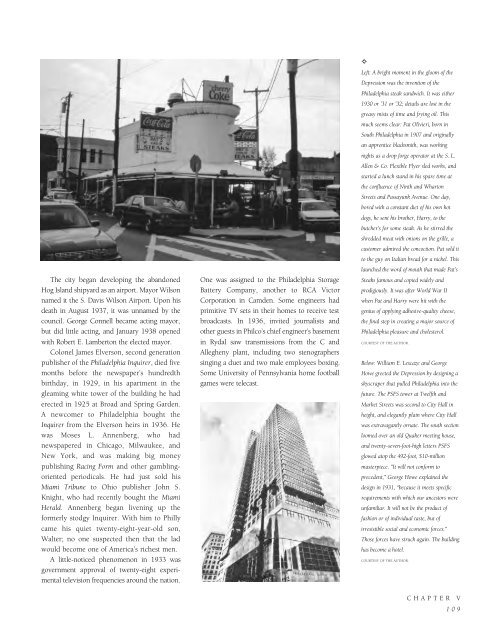

Left: A bright moment in the gloom of the<br />

Depression was the invention of the<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong> steak sandwich. It was either<br />

1930 or ’31 or ’32; details are lost in the<br />

greasy mists of time and frying oil. This<br />

much seems clear: Pat Olivieri, born in<br />

South <strong>Philadelphia</strong> in 1907 and originally<br />

an apprentice blacksmith, was working<br />

nights as a drop forge operator at the S. L.<br />

Allen & Co. Flexible Flyer sled works, and<br />

started a lunch stand in his spare time at<br />

the confluence of Ninth and Wharton<br />

Streets and Passayunk Avenue. One day,<br />

bored with a constant diet of his own hot<br />

dogs, he sent his brother, Harry, to the<br />

butcher’s for some steak. As he stirred the<br />

shredded meat with onions on the grille, a<br />

customer admired the concoction. Pat sold it<br />

to the guy on Italian bread for a nickel. This<br />

launched the word of mouth that made Pat’s<br />

Steaks famous and copied widely and<br />

prodigiously. It was after World War II<br />

when Pat and Harry were hit with the<br />

genius of applying adhesive-quality cheese,<br />

the final step in creating a major source of<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong> pleasure and cholesterol.<br />

COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR.<br />

Below: William E. Lescaze and George<br />

Howe greeted the Depression by designing a<br />

skyscraper that pulled <strong>Philadelphia</strong> into the<br />

future. The PSFS tower at Twelfth and<br />

Market Streets was second to City Hall in<br />

height, and elegantly plain where City Hall<br />

was extravagantly ornate. The south section<br />

loomed over an old Quaker meeting house,<br />

and twenty-seven-foot-high letters PSFS<br />

glowed atop the 492-foot, $10-million<br />

masterpiece. “It will not conform to<br />

precedent,” George Howe explained the<br />

design in 1931, “because it meets specific<br />

requirements with which our ancestors were<br />

unfamiliar. It will not be the product of<br />

fashion or of individual taste, but of<br />

irresistible social and economic forces.”<br />

Those forces have struck again. The building<br />

has become a hotel.<br />

COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR.<br />

CHAPTER V<br />

109