Historic Philadelphia

An illustrated history of the city of Philadelphia, paired with the histories of companies, families and organizations that make the region great.

An illustrated history of the city of Philadelphia, paired with the histories of companies, families and organizations that make the region great.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

THE BICENTENNIAL CITY<br />

WAR & PARTY CONVENTIONS<br />

In 1940 the Republican National Convention assembled again at the old Convention Hall.<br />

Wendell L. Willkie of Indiana, an erstwhile Democrat who became disenchanted with the New<br />

Deal, was anointed to oppose Roosevelt’s unprecedented third term.<br />

In the summer of 1941, Mayor Lamberton died of Lou Gehrig’s Disease, two months after<br />

Gehrig did. He was succeeded by the president of City Council, Bernard Samuel.<br />

News that the Japanese had bombed Hawaii reached <strong>Philadelphia</strong> on Sunday afternoon,<br />

December 7. Mayor Samuel felt that some local response was called for, and ordered the police to<br />

guard the Schuylkill bridges. No Japanese incursions were reported.<br />

Young men began hustling off to military service. There were thirteen thousand enlistments in<br />

the city by December 11. Factories began working around the clock; Baldwin’s plant had already<br />

shifted from locomotives to sixty-ton tanks, and navy cruisers were under construction at both<br />

Cramp’s and New York shipyards on the Delaware. Air raid sirens were tested on December 12. The<br />

first test blackout was conducted on February 3, 1942. The city’s 33,354 street lights went out when<br />

the air raid sirens sounded at 10:30. Cars pulled over and went dark. Hastily trained volunteer air<br />

raid wardens patrolled every neighborhood. Homeowners had to have black curtains on windows<br />

so lights wouldn’t show, and acquired stirrup pumps and buckets of sand in case the Japanese or<br />

Germans dropped incendiary bombs. Rationing started, of sugar, meat, coffee, gasoline, tires, shoes.<br />

Before the war’s end, nearly 184,000 <strong>Philadelphia</strong>ns had served in the armed forces, plus more<br />

than 70,000 from the Pennsylvania suburbs and 50,000 from the New Jersey suburbs. The sixcounty<br />

metropolitan area had more than 5,000 killed, nearly 3,500 from the city itself. In the<br />

metro area, 12,000 men came home wounded, 2,300 had been prisoners of war, and as of the end<br />

of 1945, another twenty-three hundred were still unaccounted for. People partied in the streets<br />

when the Japanese surrender ended the war on August 14. Governor Arthur James declared a twoday<br />

holiday; many industrial workers had been putting in seven-day weeks.<br />

The future was changed in 1945 when <strong>Philadelphia</strong> native J. Presper Eckert, Jr., and Cincinnati<br />

import John W. Mauchly, at the University of Pennsylvania’s Moore School of Engineering, led a<br />

team that put together ENIAC, the granddaddy of all digital electronic computers. That first<br />

Electronic Numerical Integrator And Calculator (ENIAC) took up two large rooms, and depended<br />

on eighteen thousand vacuum tubes which were constantly burning out; a graduate student with<br />

a basket full of tubes was on endless vigil. Eckert and Mauchly formed their own company in<br />

March 1946, gathered some young engineers from Penn and Drexel, and started work upstairs over<br />

a furniture store on Walnut Street near Twelfth to create a Universal Automatic Computer: UNI-<br />

VAC for short. The little company was sold to Remington Rand in 1950. On March 30, 1951, the<br />

U. S. Census Bureau became the purchaser of UNIVAC I. One engineer on the project wrote, “On<br />

that day, the computer industry was born.”<br />

Republicans, Democrats and the new Progressives all held presidential nominating conventions in<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong> in 1948. The GOP arrived in June, and nominated Thomas E. Dewey, widely expected<br />

to be a shoo-in over the Democrat nominee, accidentally incumbent President Harry S Truman.<br />

Former vice president Henry Wallace and some ultra-liberal leaders had whipped up a third<br />

party. The Progressive Party also met in Convention Hall, on the evening of July 23, but the next<br />

night nominated Wallace at Shibe Park before a crowd of twenty-six thousand, with folk singer<br />

Pete Seegar providing some star quality. There was an admission charge, and the ballpark’s vendors<br />

patrolled the grandstands hustling hot dogs and sodas.<br />

Chairman of the <strong>Philadelphia</strong> Convention and Visitors Bureau, and influential in bringing the<br />

two major party conventions to town, was Albert M. Greenfield. His influence on the city had<br />

✧<br />

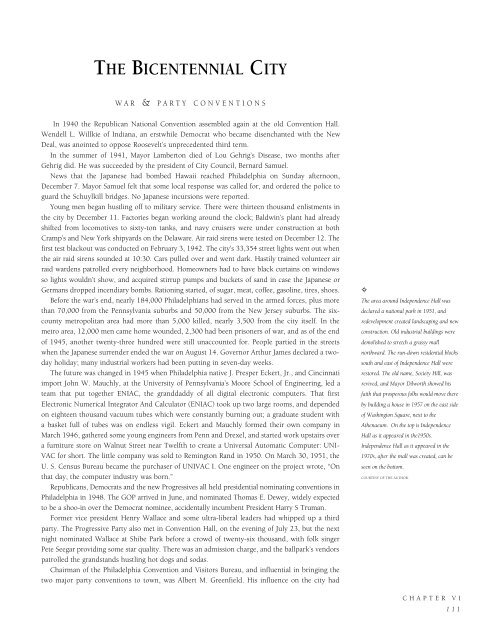

The area around Independence Hall was<br />

declared a national park in 1951, and<br />

redevelopment created landscaping and new<br />

construction. Old industrial buildings were<br />

demolished to stretch a grassy mall<br />

northward. The run-down residential blocks<br />

south and east of Independence Hall were<br />

restored. The old name, Society Hill, was<br />

revived, and Mayor Dilworth showed his<br />

faith that prosperous folks would move there<br />

by building a house in 1957 on the east side<br />

of Washington Square, next to the<br />

Athenaeum. On the top is Independence<br />

Hall as it appeared in the1950s.<br />

Independence Hall as it appeared in the<br />

1970s, after the mall was created, can be<br />

seen on the bottom.<br />

COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR.<br />

CHAPTER VI<br />

111