Historic Philadelphia

An illustrated history of the city of Philadelphia, paired with the histories of companies, families and organizations that make the region great.

An illustrated history of the city of Philadelphia, paired with the histories of companies, families and organizations that make the region great.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

✧<br />

Above: Jules Junker, who conducted a<br />

bakery at Thirteenth and Spruce Streets,<br />

owned the first automobile in the city, a De<br />

Dion-Boutton Decouville model he imported<br />

from France in 1894. It had a two-cylinder,<br />

1.75-horsepower engine. Mrs. Aimee Junker<br />

was awarded the city’s first summons for<br />

horseless speeding in 1899. She was caught<br />

doing eight miles per hour in Fairmount<br />

Park. Junker bought two small houses in the<br />

300 block of South Camac Street and had<br />

them turned into a large building to keep<br />

automobiles. It was the first garage in<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong>, although the word garage was<br />

not yet in use.<br />

COURTESY OF THE URBAN ARCHIVES, TEMPLE UNIVERSITY.<br />

had become Mayor Samuel H. Ashbridge’s<br />

secretary, with an unusual idea. Why not<br />

welcome the twentieth century on New Year’s<br />

Day, 1901, by organizing the Mummers into one<br />

big parade, on Broad Street? They would leave<br />

their neighborhoods and usual routes for part of<br />

the day, McHugh reasoned, if the city put up<br />

some cash prizes. City Council appropriated<br />

$5,000 to be spread thinly among the clubs, and<br />

the upshot was a change in <strong>Philadelphia</strong><br />

tradition. About twenty-five hundred men took<br />

part, coming up Broad Street from South Philly.<br />

There were eight of what Mummers call comic<br />

clubs, and four fancy clubs.<br />

Many Mummers groups declined the<br />

invitation to parade on Broad Street and made<br />

the usual calls on neighborhood homes. One<br />

was the Trilby String Band, described by the<br />

Evening Bulletin in 1901 as “famous as the<br />

only band of its kind in the city.” Its eighteen<br />

banjo, mandolin, and guitar players had no<br />

uniforms, but each wore a top hat and<br />

blackface. Trilby’s leader, William H. Siebrecht,<br />

said his musicians would stay in the Neck. He<br />

was afraid they would be sandwiched between<br />

two of the brass bands that accompanied other<br />

clubs, and would not be heard. “We are not<br />

running a pantomime show,” he grumbled.<br />

On June 30, 1901, Samuel C. Perkins,<br />

president of the Commission for the Erection<br />

of Public Buildings, turned over the finally<br />

completed new City Hall to Mayor Ashbridge.<br />

The project had taken thirty years, and cost<br />

$24,344,355.48.<br />

On Washington’s Birthday, 1901, John R.<br />

Hathaway, the city’s director of public works,<br />

climbed out the second floor rear window and<br />

up a ladder to the roof of a house at 422 North<br />

Twenty-second Street, followed by assorted<br />

puffing politicians and reporters. Swinging<br />

a ceremonial ebony-handled silver pick,<br />

Hathaway dislodged a brick from the chimney. It<br />

was the beginning of demolition of houses to<br />

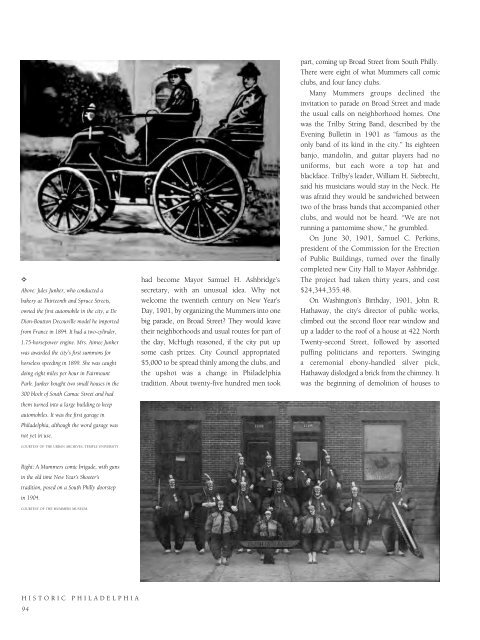

Right: A Mummers comic brigade, with guns<br />

in the old time New Year’s Shooter’s<br />

tradition, posed on a South Philly doorstep<br />

in 1904.<br />

COURTESY OF THE MUMMERS MUSEUM.<br />

HISTORIC PHILADELPHIA<br />

94