Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

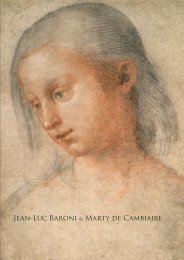

The brown tones of the painting <strong>and</strong> the facial types of the<br />

male figures help to date the work to the artist’s Bolognese<br />

apprenticeship, that is, rather early in his career. The subject<br />

is very rare: the painter at work before a large canvas whose<br />

subject is reminiscent of that invented by the Greek painter<br />

Timanthes (end of the 5 th – beginning of the 4 th century B.C.)<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>de</strong>scribed by Pliny in his Natural History as “… an artist<br />

highly gifted with genius. (…) There are also some other proofs<br />

of his genius, a Sleeping Cyclops, for instance, which he had<br />

painted upon a small panel; but being <strong>de</strong>sirous to convey<br />

the i<strong>de</strong>a of his gigantic stature, he has painted some Satyrs<br />

near him measuring his thumb with a thyrsus. Timanthes is<br />

the only one among the artists in whose works there is always<br />

something more implied by the pencil that is expressed….” 1<br />

The authors of satyric dramas also introduced Satyrs in<br />

or<strong>de</strong>r to highlight an element of the subject or to create a<br />

contrast. Although in Book IX of Odyssey there is no mention<br />

of Satyrs on the Cyclops isl<strong>and</strong>, Euripi<strong>de</strong>s introduces them<br />

in his play Cyclops making them run aground on the isl<strong>and</strong>.<br />

Satyrs compose a choir which helps Euripi<strong>de</strong>s, like the painter<br />

Timanthes in his painting, to highlight certain elements <strong>and</strong><br />

play on contrast of tones. Samuel Van Hoogstraten, painter,<br />

engraver <strong>and</strong> theoretician of the 17 th century, also commented<br />

on the subject explaining the introduction of Satyrs by the fact<br />

that the small size of Timanthes’s “tableautin” ma<strong>de</strong> it difficult<br />

to <strong>de</strong>monstrate the large size of Cyclops. 2<br />

The subject has been rarely treated in painting, unlike that<br />

of the blinding of the Cyclops that represents one of the<br />

most famous episo<strong>de</strong>s in Odysseus’s adventures. However,<br />

we can mention a prece<strong>de</strong>nt in the frescos, today lost, by<br />

Giulio Romano in the Villa Madama, which Francisco <strong>de</strong><br />

Holl<strong>and</strong>a hailed in his “Dialogues in Rome” 3 <strong>and</strong> which<br />

Vasari cited as well. There is a drawing of this composition<br />

after Giulio Romano in the Louvre, which represents The<br />

Sleeping Polyphemus surroun<strong>de</strong>d by Satyrs. Two of the<br />

Satyrs are busy measuring his feet but their size is like that<br />

of Lilliputians, which brings to mind the fact that the subject<br />

was sometimes connected with that of The Sleeping Hercules<br />

Beset by Pygmies. Both works reveal the skill of the painter to<br />

pass from one scale to another accurately reproducing correct<br />

anatomical proportions 4 . Both are equally characteristic of a<br />

certain spirit of Mannerism which combines humour with<br />

drollery <strong>and</strong> intellectual references.<br />

Surprisingly, the Cyclops has not been <strong>de</strong>picted with one eye.<br />

It is true that since Roman time, the number <strong>and</strong> location of<br />

the Cyclops’ eyes has varied <strong>de</strong>pending on interpretation.<br />

Most often, the Cyclops has been represented three-eyed<br />

with the third eye sometimes rather awkwardly placed on<br />

the forehead or at the root of the nose. However, on certain<br />

Greek kraters, the third eye is mising. And the Cyclops on<br />

the frescos of the House of Meleager, Pompei, also seems to<br />

have two eyes. Thus, the execution of the Cyclops’s third eye<br />

seems to have long created problems to the artists, certainly<br />

because it ren<strong>de</strong>red his appearance monstrous. In the present<br />

painting, Ferretti might have wanted to show the incomplete<br />

stage of the painting insi<strong>de</strong> the painting <strong>and</strong> that the artist<br />

represented from behind may have kept this important <strong>de</strong>tail<br />

for the final stage. It might have also been a way of voluntarily<br />

complicating the i<strong>de</strong>ntification of unusual imagery in or<strong>de</strong>r to<br />

confuse or entertain collectors <strong>and</strong> patrons.<br />

Although the technique is more sketched than usual, this<br />

small-size work perfectly reveals the humour characteristic<br />

of Ferretti’s art, rather approaching it to a sort of caricature,<br />

burlesque. Exaggerated musculature, exaggeratedly large<br />

feet with the toes rather resembling small logs, the dynamic<br />

pose of the painter <strong>and</strong> the liking for a roun<strong>de</strong>d, full, plump<br />

execution are all typical of Ferretti <strong>and</strong> can be found in his<br />

other works, especially those of the beginning of his career.<br />

1 Pliny the El<strong>de</strong>r, Natural History, trans. by John Bostock<br />

(London, 1857).<br />

2 Samuel Van Hoogstraten, Introduction à la haute école<br />

<strong>de</strong> l’art <strong>de</strong> peinture, Droz, Geneva, 2006, translation,<br />

comments <strong>and</strong> in<strong>de</strong>x by Jan Blanc, p. 310.<br />

3 Francisco <strong>de</strong> Holl<strong>and</strong>a, Four Dialogues on Painting, Book<br />

II<br />

4 The correspon<strong>de</strong>nce between these two subjects was<br />

mentioned by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729-1782) in<br />

his Frammenti <strong>de</strong>lla seconda parte <strong>de</strong>l Laocoonte, Milano<br />

Edizioni, 1841, p. 46-49.<br />

Gabriel André <strong>de</strong> Bonneval<br />

Coussac-Bonneval 1769 – Saint-Myon 1839<br />

Bouquet of Flowers on the edge of a fountain: Imperial<br />

Lilies, Tulips, Double Hollyhocks, White Lilies, Gerberas,<br />

Peonies, White Roses, Roses, Ipomoeas <strong>and</strong> Carnations<br />

Oil on canvas<br />

Signed <strong>and</strong> dated G A <strong>de</strong> Bonneval 1810 at lower right<br />

117 x 91 cm (46 3 /8 x 35 7 /8 in.)<br />

Exhibited<br />

Possibly Paris, 1810 Salon, No. 100.<br />

An amateur artist, Gabriel André <strong>de</strong> Bonneval is little known<br />

today. From a family of knightly extraction admitted to the<br />

court in 1786 <strong>and</strong> 1789, he studied in the Royal Military<br />

School in Effiat, probably at the same time as Louis Charles<br />

Antoine Desaix who was <strong>de</strong>stined to become a great general<br />

of Napoleonic campaigns. Bonneval then became a page<br />

of the Gr<strong>and</strong>e Ecurie in 1783. Sous-lieutenant in Clermont<br />

in 1787, captain in the regiment of Poitou <strong>and</strong> the regiment<br />

of Berry during the Revolution, <strong>and</strong> captain of the Horse<br />

Guards of the constitutional guard of the King, Bonneval<br />

was seriously woun<strong>de</strong>d for valiantly <strong>de</strong>fending the estate of<br />

Chantilly, which earned him the recognition of the prince <strong>de</strong><br />

Condé <strong>and</strong> the granting of the or<strong>de</strong>r of Saint-Louis. Barely<br />

recovered, he was imprisoned for fifteen months, after which<br />

period he was released by his prison guard <strong>and</strong> managed<br />

to emigrate. According to the Illustrations <strong>de</strong> la Noblesse<br />

Européenne, “during the creation of stud farms in 1806,<br />

he was sought after by Napoleon <strong>and</strong> since that time until<br />

1832, he had comm<strong>and</strong>ed with the titles of directeur <strong>and</strong><br />

120