Adventure Magazine

Issue 237: Survival Issue

Issue 237: Survival Issue

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

"The bivvy boulder in Trinidad is in<br />

the forest, but no less magical."<br />

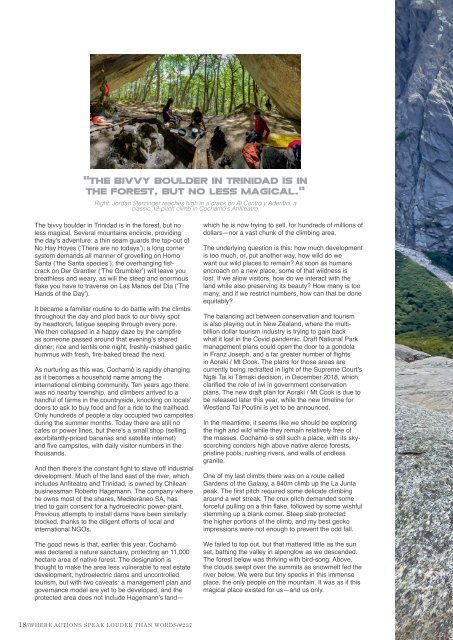

Right: Jordan Sterzinger reaches high in a crack on Al Centro y Adentro, a<br />

classic 12-pitch climb in Cochamó's Anfiteatro.<br />

The bivvy boulder in Trinidad is in the forest, but no<br />

less magical. Several mountains encircle, providing<br />

the day's adventure: a thin seam guards the top-out of<br />

No Hay Hoyes (‘There are no todays’); a long corner<br />

system demands all manner of grovelling on Homo<br />

Santa (‘the Santa species’); the overhanging fistcrack<br />

on Der Grantler (‘The Grumbler’) will leave you<br />

breathless and weary, as will the steep and enormous<br />

flake you have to traverse on Las Manos del Dia (‘The<br />

Hands of the Day’).<br />

It became a familiar routine to do battle with the climbs<br />

throughout the day and plod back to our bivvy spot<br />

by headtorch, fatigue seeping through every pore.<br />

We then collapsed in a happy daze by the campfire<br />

as someone passed around that evening’s shared<br />

dinner; rice and lentils one night, freshly-mashed garlic<br />

hummus with fresh, fire-baked bread the next.<br />

As nurturing as this was, Cochamó is rapidly changing<br />

as it becomes a household name among the<br />

international climbing community. Ten years ago there<br />

was no nearby township, and climbers arrived to a<br />

handful of farms in the countryside, knocking on locals’<br />

doors to ask to buy food and for a ride to the trailhead.<br />

Only hundreds of people a day occupied two campsites<br />

during the summer months. Today there are still no<br />

cafes or power lines, but there's a small shop (selling<br />

exorbitantly-priced bananas and satellite internet)<br />

and five campsites, with daily visitor numbers in the<br />

thousands.<br />

And then there’s the constant fight to stave off industrial<br />

development. Much of the land east of the river, which<br />

includes Anfiteatro and Trinidad, is owned by Chilean<br />

businessman Roberto Hagemann. The company where<br />

he owns most of the shares, Mediteráneo SA, has<br />

tried to gain consent for a hydroelectric power-plant.<br />

Previous attempts to install dams have been similarly<br />

blocked, thanks to the diligent efforts of local and<br />

international NGOs.<br />

The good news is that, earlier this year, Cochamó<br />

was declared a nature sanctuary, protecting an 11,000<br />

hectare area of native forest. The designation is<br />

thought to make the area less vulnerable to real estate<br />

development, hydroelectric dams and uncontrolled<br />

tourism, but with two caveats: a management plan and<br />

governance model are yet to be developed, and the<br />

protected area does not include Hagemann’s land—<br />

which he is now trying to sell, for hundreds of millions of<br />

dollars—nor a vast chunk of the climbing area.<br />

The underlying question is this: how much development<br />

is too much, or, put another way, how wild do we<br />

want our wild places to remain? As soon as humans<br />

encroach on a new place, some of that wildness is<br />

lost. If we allow visitors, how do we interact with the<br />

land while also preserving its beauty? How many is too<br />

many, and if we restrict numbers, how can that be done<br />

equitably?<br />

The balancing act between conservation and tourism<br />

is also playing out in New Zealand, where the multibillion<br />

dollar tourism industry is trying to gain back<br />

what it lost in the Covid pandemic. Draft National Park<br />

management plans could open the door to a gondola<br />

in Franz Joseph, and a far greater number of flights<br />

in Aoraki / Mt Cook. The plans for those areas are<br />

currently being redrafted in light of the Supreme Court’s<br />

Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki decision, in December 2018, which<br />

clarified the role of iwi in government conservation<br />

plans. The new draft plan for Aoraki / Mt Cook is due to<br />

be released later this year, while the new timeline for<br />

Westland Tai Poutini is yet to be announced.<br />

In the meantime, it seems like we should be exploring<br />

the high and wild while they remain relatively free of<br />

the masses. Cochamó is still such a place, with its skyscorching<br />

condors high above native alerce forests,<br />

pristine pools, rushing rivers, and walls of endless<br />

granite.<br />

One of my last climbs there was on a route called<br />

Gardens of the Galaxy, a 840m climb up the La Junta<br />

peak. The first pitch required some delicate climbing<br />

around a wet streak. The crux pitch demanded some<br />

forceful pulling on a thin flake, followed by some wishful<br />

stemming up a blank corner. Steep slab protected<br />

the higher portions of the climb, and my best gecko<br />

impressions were not enough to prevent the odd fall.<br />

We failed to top out, but that mattered little as the sun<br />

set, bathing the valley in alpenglow as we descended.<br />

The forest below was thriving with bird-song. Above,<br />

the clouds swept over the summits as snowmelt fed the<br />

river below. We were but tiny specks in this immense<br />

place, the only people on the mountain. It was as if this<br />

magical place existed for us—and us only.<br />

18//WHERE ACTIONS SPEAK LOUDER THAN WORDS/#237