The Teaching and Learning Innovation Digest - May 2023

Welcome to a truly special edition of the Teaching and Learning Innovation Digest! Our seventh annual academic publication has assumed an incredibly meaningful shape and form for a number of reasons. Not only did we receive an enthusiastic response with over 30 submissions via our institutional broadcast, but we also have consciously and intentionally embraced the principles of Universal Design for Learning by attempting to represent and celebrate the varied forms of expressions therein. From reflective essays, poetry, visual and performing arts, podcasts, video conversations to scholarly work, academic and applied research, news and updates, and interviews, this is truly a power-packed publication!

Welcome to a truly special edition of the Teaching and Learning Innovation Digest! Our seventh annual academic publication has assumed an incredibly meaningful shape and form for a number of reasons. Not only did we receive an enthusiastic response with over 30 submissions via our institutional broadcast, but we also have consciously and intentionally embraced the principles of Universal Design for Learning by attempting to represent and celebrate the varied forms of expressions therein. From reflective essays, poetry, visual and performing arts, podcasts, video conversations to scholarly work, academic and applied research, news and updates, and interviews, this is truly a power-packed publication!

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

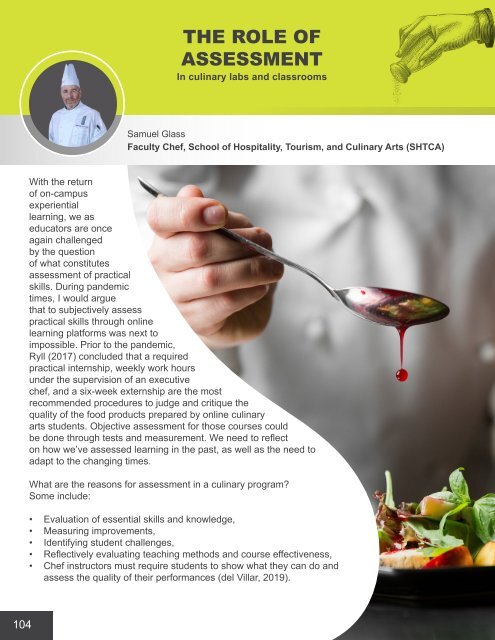

THE ROLE OF<br />

ASSESSMENT<br />

In culinary labs <strong>and</strong> classrooms<br />

Samuel Glass<br />

Faculty Chef, School of Hospitality, Tourism, <strong>and</strong> Culinary Arts (SHTCA)<br />

With the return<br />

of on-campus<br />

experiential<br />

learning, we as<br />

educators are once<br />

again challenged<br />

by the question<br />

of what constitutes<br />

assessment of practical<br />

skills. During p<strong>and</strong>emic<br />

times, I would argue<br />

that to subjectively assess<br />

practical skills through online<br />

learning platforms was next to<br />

impossible. Prior to the p<strong>and</strong>emic,<br />

Ryll (2017) concluded that a required<br />

practical internship, weekly work hours<br />

under the supervision of an executive<br />

chef, <strong>and</strong> a six-week externship are the most<br />

recommended procedures to judge <strong>and</strong> critique the<br />

quality of the food products prepared by online culinary<br />

arts students. Objective assessment for those courses could<br />

be done through tests <strong>and</strong> measurement. We need to reflect<br />

on how we’ve assessed learning in the past, as well as the need to<br />

adapt to the changing times.<br />

What are the reasons for assessment in a culinary program?<br />

Some include:<br />

• Evaluation of essential skills <strong>and</strong> knowledge,<br />

• Measuring improvements,<br />

• Identifying student challenges,<br />

• Reflectively evaluating teaching methods <strong>and</strong> course effectiveness,<br />

• Chef instructors must require students to show what they can do <strong>and</strong><br />

assess the quality of their performances (del Villar, 2019).<br />

At a recent faculty meeting, one of the<br />

questions posed was “what constitutes 100<br />

per cent in a practical setting?” Is perfection<br />

possible in a practical application where the<br />

assessment is subjective? That question has<br />

caused myself <strong>and</strong> others to reflect on what<br />

constitutes assessment for practical skills<br />

<strong>and</strong> what methods can be used. I believe that<br />

there are two categories of assessment related<br />

to practical labs <strong>and</strong> classrooms: objective<br />

<strong>and</strong> subjective.<br />

Objective assessment, as related to practical<br />

applications <strong>and</strong> evaluations, is either black<br />

or white. <strong>The</strong>re is no grey zone. Each task/<br />

question has a single correct answer or<br />

objective that needs to be met. For example,<br />

if a student is required to cut a piece of<br />

white turnip into a one-inch cube, it can be<br />

measured. If that cube is 1”x1”x1”, then a<br />

perfect grade is warranted. If the cube is<br />

either larger or smaller, then it is not perfect<br />

<strong>and</strong> does not meet the st<strong>and</strong>ard/grade, <strong>and</strong><br />

the grade for the imperfect one would reflect<br />

that. Another example would be if a student<br />

is required to cook a roast to an internal<br />

temperature of 125˚F <strong>and</strong> ends up cooking it to<br />

140˚F. <strong>The</strong> evaluator has an objective outcome<br />

that has not been met <strong>and</strong> the student would<br />

be graded accordingly.<br />

Subjective assessment is based on the opinion<br />

of the evaluator <strong>and</strong> often based on rubrics<br />

<strong>and</strong> criteria being met. But what makes that<br />

evaluator’s opinion valid? Is the evaluator<br />

a subject matter expert or not? Is there a<br />

difference between a faculty member new<br />

to teaching <strong>and</strong> one with multiple years of<br />

experience when it comes to an underst<strong>and</strong>ing<br />

of assessment types <strong>and</strong> evaluation?<br />

According to Eisner (1990), “the ability to make<br />

fine-grained discrimination among complex <strong>and</strong><br />

subtle qualities is an instance of what I have<br />

called connoisseurship. Connoisseurship is the<br />

art of appreciation” (p. 63). Eisner continues:<br />

“In its customary mode, connoisseurship<br />

is concerned with matters of quality, in the<br />

sense of value. Connoisseurs of wine [<strong>and</strong><br />

food], of art, of carpentry are typically those<br />

who can discern the value of what they attend<br />

to. <strong>The</strong>y can often [<strong>and</strong> should be able to]<br />

provide reasons for their judgment” (p. 69).<br />

104<br />

105