Lot's Wife Edition 1 2017

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

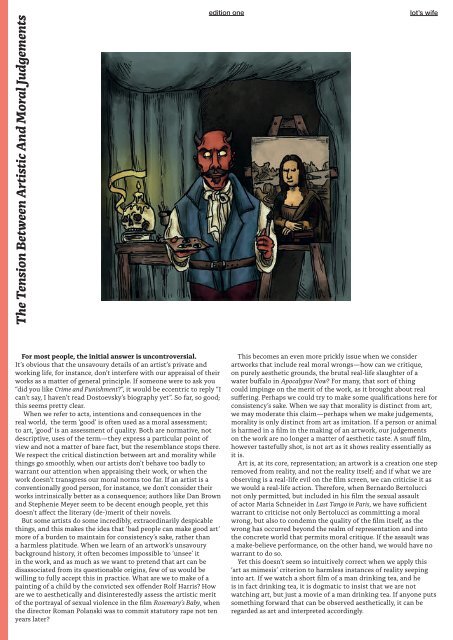

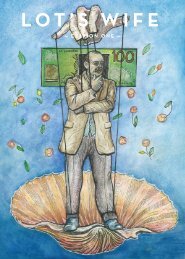

The Tension Between Artistic And Moral Judgements<br />

edition one<br />

lot’s wife<br />

For most people, the initial answer is uncontroversial.<br />

It’s obvious that the unsavoury details of an artist’s private and<br />

working life, for instance, don’t interfere with our appraisal of their<br />

works as a matter of general principle. If someone were to ask you<br />

“did you like Crime and Punishment?”, it would be eccentric to reply “I<br />

can’t say, I haven’t read Dostoevsky’s biography yet”. So far, so good;<br />

this seems pretty clear.<br />

When we refer to acts, intentions and consequences in the<br />

real world, the term ‘good’ is often used as a moral assessment;<br />

to art, ‘good’ is an assessment of quality. Both are normative, not<br />

descriptive, uses of the term—they express a particular point of<br />

view and not a matter of bare fact, but the resemblance stops there.<br />

We respect the critical distinction between art and morality while<br />

things go smoothly, when our artists don’t behave too badly to<br />

warrant our attention when appraising their work, or when the<br />

work doesn’t transgress our moral norms too far. If an artist is a<br />

conventionally good person, for instance, we don’t consider their<br />

works intrinsically better as a consequence; authors like Dan Brown<br />

and Stephenie Meyer seem to be decent enough people, yet this<br />

doesn’t affect the literary (de-)merit of their novels.<br />

But some artists do some incredibly, extraordinarily despicable<br />

things, and this makes the idea that ‘bad people can make good art’<br />

more of a burden to maintain for consistency’s sake, rather than<br />

a harmless platitude. When we learn of an artwork’s unsavoury<br />

background history, it often becomes impossible to ‘unsee’ it<br />

in the work, and as much as we want to pretend that art can be<br />

disassociated from its questionable origins, few of us would be<br />

willing to fully accept this in practice. What are we to make of a<br />

painting of a child by the convicted sex offender Rolf Harris? How<br />

are we to aesthetically and disinterestedly assess the artistic merit<br />

of the portrayal of sexual violence in the film Rosemary’s Baby, when<br />

the director Roman Polanski was to commit statutory rape not ten<br />

years later?<br />

This becomes an even more prickly issue when we consider<br />

artworks that include real moral wrongs—how can we critique,<br />

on purely aesthetic grounds, the brutal real-life slaughter of a<br />

water buffalo in Apocalypse Now? For many, that sort of thing<br />

could impinge on the merit of the work, as it brought about real<br />

suffering. Perhaps we could try to make some qualifications here for<br />

consistency’s sake. When we say that morality is distinct from art,<br />

we may moderate this claim—perhaps when we make judgements,<br />

morality is only distinct from art as imitation. If a person or animal<br />

is harmed in a film in the making of an artwork, our judgements<br />

on the work are no longer a matter of aesthetic taste. A snuff film,<br />

however tastefully shot, is not art as it shows reality essentially as<br />

it is.<br />

Art is, at its core, representation; an artwork is a creation one step<br />

removed from reality, and not the reality itself; and if what we are<br />

observing is a real-life evil on the film screen, we can criticise it as<br />

we would a real-life action. Therefore, when Bernardo Bertolucci<br />

not only permitted, but included in his film the sexual assault<br />

of actor Maria Schneider in Last Tango in Paris, we have sufficient<br />

warrant to criticise not only Bertolucci as committing a moral<br />

wrong, but also to condemn the quality of the film itself, as the<br />

wrong has occurred beyond the realm of representation and into<br />

the concrete world that permits moral critique. If the assault was<br />

a make-believe performance, on the other hand, we would have no<br />

warrant to do so.<br />

Yet this doesn’t seem so intuitively correct when we apply this<br />

‘art as mimesis’ criterion to harmless instances of reality seeping<br />

into art. If we watch a short film of a man drinking tea, and he<br />

is in fact drinking tea, it is dogmatic to insist that we are not<br />

watching art, but just a movie of a man drinking tea. If anyone puts<br />

something forward that can be observed aesthetically, it can be<br />

regarded as art and interpreted accordingly.