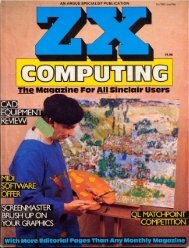

ZX Computings - OpenLibra

ZX Computings - OpenLibra

ZX Computings - OpenLibra

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

the blank to remove the black<br />

blob. This blank is printed just<br />

before the screen SCROLLS upward,<br />

to move all the zeroes upward.<br />

Your aim in the game —<br />

needless to say — is to avoid<br />

the hailstones, as you can see<br />

from diagram two. You'll<br />

remember that at the start of<br />

this article we mentioned that<br />

the RND function was fairly<br />

slow. To minimise the delay,<br />

we've used a single pair of random<br />

numbers (generated in<br />

lines 60 and 65) four times in<br />

line 70.<br />

Lines 1 00 and 110 are very<br />

interesting, and are crucial for<br />

producing a worthwhile program<br />

using the SCROLL facility.<br />

Line 100 moves the PRINT AT<br />

position to A + C, B which is a<br />

line down from where the black<br />

blob is at present. Using line<br />

110, the computer then looks<br />

up this position in the display<br />

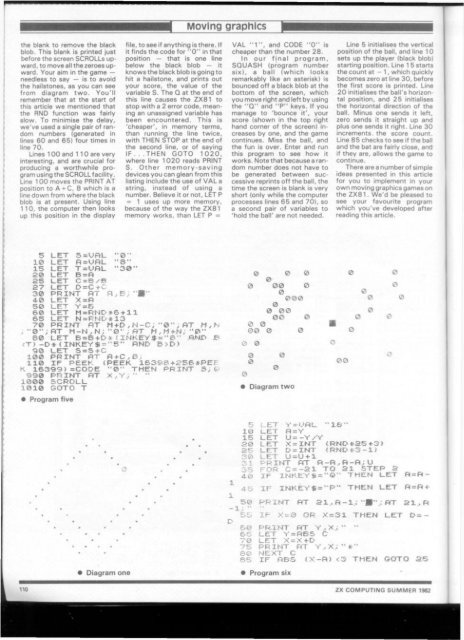

5<br />

10<br />

15<br />

£ 0<br />

25<br />

27<br />

LET S =VRL *"0"<br />

LET R = URL "8"<br />

LET T = UftL "30<br />

LET B = R<br />

LET C = B / B<br />

LET D =C +c<br />

file, to see if anything is there. If<br />

it finds the code for' 0" in that<br />

position — that is one line<br />

below the black blob — it<br />

knows the black blob is going to<br />

hit a hailstone, and prints out<br />

your score, the value of the<br />

variable S. The Q at the end of<br />

this line causes the <strong>ZX</strong>81 to<br />

stop with a 2 error code, meaning<br />

an unassigned variable has<br />

been encountered. This is<br />

'cheaper', in memory terms,<br />

than running the line twice,<br />

with THEN STOP at the end of<br />

the second line, or of saying<br />

IF . . .THEN GOTO 1020,<br />

where line 1020 reads PRINT<br />

S. Other memory-saving<br />

devices you can glean from this<br />

listing include the use of VAL a<br />

string, instead of using a<br />

number. Believe it or not, LET P<br />

= 1 uses up more memory,<br />

because of the way the <strong>ZX</strong>81<br />

memory works, than LET P =<br />

30 PRINT RT '<br />

4-0 LET X=R<br />

50 LET Y=6<br />

60 LET M =RND*6 +11<br />

65 LET N=PND*13<br />

70 PRINT RT M+D,N-C, "0"; RT M,N<br />

j"0";RT M - N . N ; " 0 ' ; P T M,M+N;"0"<br />

60 LET B=B+D* (INKEY$ = "8" .RNT> f<br />

v'T) -D* ( INKEY$-"5" RND B >D)<br />

90 LET S = S+C<br />

100 PRINT RT R+C,B;<br />

110 IF PEEK (PEEK 16398 +256 frPEf<br />

K 16399) =CODE "0" THEN PRINT 5, CV<br />

990 PRINT RT X^Y;" "<br />

1000 SCROLL<br />

1010 GOTO T<br />

• Program five<br />

Moving graphics<br />

VAL "1", and CODE "0" is<br />

cheaper than the number 28.<br />

In our final program,<br />

SQUASH (program number<br />

six), a ball (which looks<br />

remarkably like an asterisk) is<br />

bounced off a black blob at the<br />

bottom of the screen, which<br />

you move right and left by using<br />

the "Q" and "P" keys. If you<br />

manage to 'bounce it', your<br />

score (shown in the top right<br />

hand corner of the screen) increases<br />

by one, and the game<br />

continues. Miss the ball, and<br />

the fun is over. Enter and run<br />

this program to see how it<br />

works. Note that because a random<br />

number does not have to<br />

be generated between successive<br />

reprints off the ball, the<br />

time the screen is blank is very<br />

short (only while the computer<br />

processes lines 65 and 70), so<br />

a second pair of variables to<br />

'hold the ball' are not needed.<br />

0 0 0<br />

0<br />

0 00 0<br />

0<br />

000<br />

0<br />

0 00<br />

0 0 0<br />

0 0<br />

00 0 0<br />

0 0<br />

0 0<br />

0<br />

0<br />

0<br />

Diagram two<br />

5 LET Y -<br />

10 LET R =<br />

P • 15 LET U =<br />

• » • • 20 LET X —<br />

• * • • 2 5 LET D =<br />

• • 3 0 LET U =<br />

• • • 31 PRINT<br />

0 • 3 5 FOR C =<br />

m 4-0 IP INK<br />

ft 1<br />

• • 4 5 IF INK<br />

• a 1<br />

• ft 5© PRINT<br />

* * — 1; "<br />

• • 5 5 IF X-0<br />

ft * D<br />

• * • 6 0 P R I N T l<br />

« • • 6 6 LET Y =<br />

m • 7 0 LET X=<br />

• • ft 7 5 PR INT (<br />

• v<br />

8 0 NEXT C<br />

8 5 IF RBS<br />

• Diagram one • Program six<br />

0<br />

mm<br />

Line 5 initialises the vertical<br />

position of the ball, and line 10<br />

sets up the player (black blob)<br />

starting position. Line 1 5 starts<br />

the count at - 1, which quickly<br />

becomes zero at line 30, before<br />

the first score is printed. Line<br />

20 initialises the ball's horizontal<br />

position, and 25 initialises<br />

the horizontal direction of the<br />

ball. Minus one sends it left,<br />

zero sends it straight up and<br />

plus one sends it right. Line 30<br />

increments, the score count.<br />

Line 85 checks to see if the ball<br />

and the bat are fairly close, and<br />

if they are, allows the game to<br />

continue.<br />

There are a number of simple<br />

ideas presented in this article<br />

for you to implement in your<br />

own moving graphics games on<br />

the <strong>ZX</strong>81. We'd be pleased to<br />

see your favourite program<br />

which you've developed after<br />

reading this article.<br />

00<br />

1 6 "<br />

0 0<br />

0<br />

0<br />

0 0<br />

0<br />

0<br />

0 0<br />

(RND*25 +3)<br />