Ch. 54 – Biliary System

Ch. 54 – Biliary System

Ch. 54 – Biliary System

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

1584 Section X Abdomen<br />

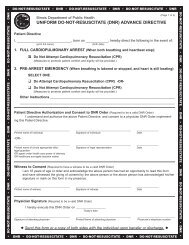

Figure <strong>54</strong>-36 Computed tomography scan visualizes mass at<br />

hepatic duct bifurcation (arrow) resulting in bilateral biliary<br />

dilation and extensive perihilar malignancy.<br />

tumor, including involvement of the bile ducts, liver, hilar<br />

vessels, and distant metastases. The initial radiographic<br />

studies consist of either abdominal ultrasound or CT<br />

scanning (Fig. <strong>54</strong>-36). Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas<br />

are easily visualized on CT scans; however, perihilar and<br />

distal tumors are often diffi cult to visualize on ultrasound<br />

and standard CT scan. <strong>Ch</strong>olangiocarcinoma can be<br />

enhanced by using delayed-phase CT acquisition (10<br />

minutes after contrast injection). A hilar cholangiocarcinoma<br />

gives a picture of a dilated intrahepatic biliary tree<br />

and a normal or collapsed gallbladder and extrahepatic<br />

biliary tree. Distal tumors lead to dilation of the gallbladder<br />

and both the intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary<br />

tree.<br />

After documentation of bile duct dilation, biliary<br />

anatomy has been traditionally defi ned cholangiographically<br />

through either the percutaneous transhepatic or the<br />

endoscopic retrograde route. The most proximal extent<br />

of the tumor is the most important feature in determining<br />

resectability in patients with perihilar tumors, and the<br />

percutaneous route is favored in these patients because<br />

it defi nes the proximal extent of tumor involvement most<br />

reliably. PET will detect unsuspected distant or intrahepatic<br />

metastases in up to 30% of patients with cholangiocarcinoma.<br />

MRC offers good resolution of both the<br />

intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary tree, but should be<br />

substituted with PTC or ERCP in patients that will require<br />

preoperative or palliative biliary drainage. <strong>Biliary</strong> drainage<br />

is necessary if the patient’s bilirubin is more than<br />

10 mg/dL, but it has been associated with an increased<br />

risk for cholangitis and longer postoperative hospital stay<br />

in patients with obstructive jaundice who then undergo<br />

resection. 46 <strong>Ch</strong>olestasis, biliary cirrhosis, and liver dys-<br />

Box <strong>54</strong>-8 Radiologic Criteria to Suggest<br />

Unresectability of <strong>Ch</strong>olangiocarcinoma<br />

Bilateral hepatic duct involvement up to secondary radicals<br />

Bilateral hepatic artery involvement<br />

Encasement of the portal vein proximal to its bifurcation<br />

Atrophy of one hepatic lobe with contralateral portal vein<br />

encasement<br />

Atrophy of one hepatic lobe with contralateral biliary radical<br />

involvement<br />

Distant metastasis<br />

Adapted from Anderson CD, Pinson CW, Berlin J, <strong>Ch</strong>ari RS: Diagnosis<br />

and treatment of cholangiocarcinoma. Oncologist 9:43-57, 2004.<br />

function develop rapidly in the face of unrelieved biliary<br />

obstruction.<br />

Percutaneous fi ne-needle aspiration biopsy, brush and<br />

scrape biopsy, and cytologic examination of bile all have<br />

been used to establish a tissue diagnosis; however, the<br />

sensitivity in detecting a malignancy is low, and a benign<br />

result should be considered unreliable. Seven to 15% of<br />

patients with preoperative symptoms and imaging studies<br />

and intraoperative fi ndings consistent with malignant<br />

biliary obstruction will ultimately have benign lesions on<br />

histologic analysis of resection specimens.<br />

Management<br />

Hepatic lobar atrophy and hepatic ductal extension<br />

predict the need for hepatectomy in order to achieve a<br />

margin-negative resection. 45,47 All available data must be<br />

used to distinguish resectability from unresectability (Fig.<br />

<strong>54</strong>-37). Radiographic criteria that suggest unresectability<br />

of perihilar tumors include bilateral hepatic duct involvement<br />

up to secondary radicals, encasement or occlusion<br />

of the portal vein proximal to its bifurcation, atrophy of<br />

one liver lobe with encasement of the contralateral portal<br />

vein branch, involvement of bilateral hepatic arteries, or<br />

atrophy of one liver lobe with contralateral secondary<br />

biliary radical involvement (Box <strong>54</strong>-8). Ipsilateral portal<br />

vein involvement and involvement of secondary biliary<br />

radicals do not preclude resection, nor does ipsilateral<br />

lobar atrophy. 48 Curative treatment of patients with cholangiocarcinoma<br />

is possible only with complete resection<br />

(R0).<br />

Patients with unequivocal evidence of unresectable<br />

cholangiocarcinoma at initial evaluation are palliated<br />

nonoperatively. Nonoperative palliation can be achieved<br />

both endoscopically and percutaneously. Percutaneous<br />

biliary drainage has several advantages over endoscopic<br />

management in patients with perihilar cholangiocarcinoma,<br />

whereas endoscopic palliation is the preferred<br />

approach in patients with distal cholangiocarcinoma.<br />

More recently, metallic stents have been used to palliate<br />

patients with malignant biliary obstruction. These stents<br />

remain patent longer than plastic stents and require fewer<br />

subsequent manipulations.<br />

Operative Approach<br />

Surgical exploration should be undertaken in good-risk<br />

patients without evidence of metastatic or locally unre-