Chapter 2. Progress towards the EFA goals - Unesco

Chapter 2. Progress towards the EFA goals - Unesco

Chapter 2. Progress towards the EFA goals - Unesco

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

0<br />

1<br />

0<br />

CHAPTER 2<br />

2<br />

Education for All Global Monitoring Report<br />

Removing cost barriers to vital maternal and<br />

child health services. Inability to pay is a major<br />

factor limiting access to basic maternal and<br />

child health services (Gilson and McIntyre, 2005;<br />

Pearson, 2004). Recent experience from<br />

countries including Ghana, Nepal, Senegal,<br />

Uganda and Zambia provides evidence that<br />

eliminating charges for basic health services<br />

is often followed by a rapid rise in <strong>the</strong> uptake<br />

of services, especially by <strong>the</strong> poor (Deininger<br />

and Mpuga, 2005; Yates, 2009) (Box <strong>2.</strong>2).<br />

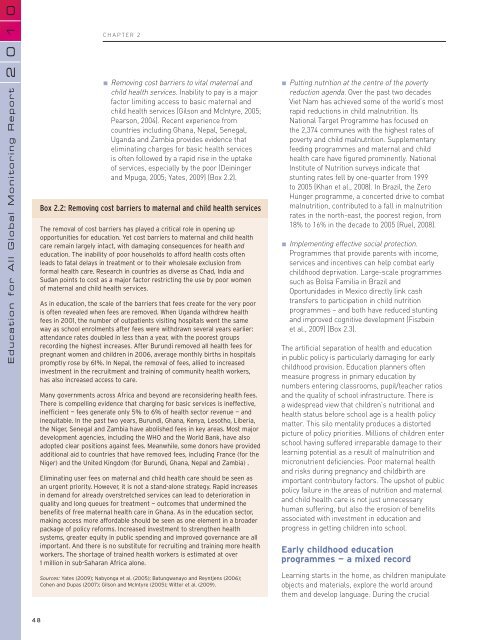

Box <strong>2.</strong>2: Removing cost barriers to maternal and child health services<br />

The removal of cost barriers has played a critical role in opening up<br />

opportunities for education. Yet cost barriers to maternal and child health<br />

care remain largely intact, with damaging consequences for health and<br />

education. The inability of poor households to afford health costs often<br />

leads to fatal delays in treatment or to <strong>the</strong>ir wholesale exclusion from<br />

formal health care. Research in countries as diverse as Chad, India and<br />

Sudan points to cost as a major factor restricting <strong>the</strong> use by poor women<br />

of maternal and child health services.<br />

As in education, <strong>the</strong> scale of <strong>the</strong> barriers that fees create for <strong>the</strong> very poor<br />

is often revealed when fees are removed. When Uganda withdrew health<br />

fees in 2001, <strong>the</strong> number of outpatients visiting hospitals went <strong>the</strong> same<br />

way as school enrolments after fees were withdrawn several years earlier:<br />

attendance rates doubled in less than a year, with <strong>the</strong> poorest groups<br />

recording <strong>the</strong> highest increases. After Burundi removed all health fees for<br />

pregnant women and children in 2006, average monthly births in hospitals<br />

promptly rose by 61%. In Nepal, <strong>the</strong> removal of fees, allied to increased<br />

investment in <strong>the</strong> recruitment and training of community health workers,<br />

has also increased access to care.<br />

Many governments across Africa and beyond are reconsidering health fees.<br />

There is compelling evidence that charging for basic services is ineffective,<br />

inefficient — fees generate only 5% to 6% of health sector revenue — and<br />

inequitable. In <strong>the</strong> past two years, Burundi, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia,<br />

<strong>the</strong> Niger, Senegal and Zambia have abolished fees in key areas. Most major<br />

development agencies, including <strong>the</strong> WHO and <strong>the</strong> World Bank, have also<br />

adopted clear positions against fees. Meanwhile, some donors have provided<br />

additional aid to countries that have removed fees, including France (for <strong>the</strong><br />

Niger) and <strong>the</strong> United Kingdom (for Burundi, Ghana, Nepal and Zambia) .<br />

Eliminating user fees on maternal and child health care should be seen as<br />

an urgent priority. However, it is not a stand-alone strategy. Rapid increases<br />

in demand for already overstretched services can lead to deterioration in<br />

quality and long queues for treatment — outcomes that undermined <strong>the</strong><br />

benefits of free maternal health care in Ghana. As in <strong>the</strong> education sector,<br />

making access more affordable should be seen as one element in a broader<br />

package of policy reforms. Increased investment to streng<strong>the</strong>n health<br />

systems, greater equity in public spending and improved governance are all<br />

important. And <strong>the</strong>re is no substitute for recruiting and training more health<br />

workers. The shortage of trained health workers is estimated at over<br />

1 million in sub-Saharan Africa alone.<br />

Sources: Yates (2009); Nabyonga et al. (2005); Batungwanayo and Reyntjens (2006);<br />

Cohen and Dupas (2007); Gilson and McIntyre (2005); Witter et al. (2009).<br />

Putting nutrition at <strong>the</strong> centre of <strong>the</strong> poverty<br />

reduction agenda. Over <strong>the</strong> past two decades<br />

Viet Nam has achieved some of <strong>the</strong> world’s most<br />

rapid reductions in child malnutrition. Its<br />

National Target Programme has focused on<br />

<strong>the</strong> 2,374 communes with <strong>the</strong> highest rates of<br />

poverty and child malnutrition. Supplementary<br />

feeding programmes and maternal and child<br />

health care have figured prominently. National<br />

Institute of Nutrition surveys indicate that<br />

stunting rates fell by one-quarter from 1999<br />

to 2005 (Khan et al., 2008). In Brazil, <strong>the</strong> Zero<br />

Hunger programme, a concerted drive to combat<br />

malnutrition, contributed to a fall in malnutrition<br />

rates in <strong>the</strong> north-east, <strong>the</strong> poorest region, from<br />

18% to 16% in <strong>the</strong> decade to 2005 (Ruel, 2008).<br />

Implementing effective social protection.<br />

Programmes that provide parents with income,<br />

services and incentives can help combat early<br />

childhood deprivation. Large-scale programmes<br />

such as Bolsa Familia in Brazil and<br />

Oportunidades in Mexico directly link cash<br />

transfers to participation in child nutrition<br />

programmes – and both have reduced stunting<br />

and improved cognitive development (Fiszbein<br />

et al., 2009) (Box <strong>2.</strong>3).<br />

The artificial separation of health and education<br />

in public policy is particularly damaging for early<br />

childhood provision. Education planners often<br />

measure progress in primary education by<br />

numbers entering classrooms, pupil/teacher ratios<br />

and <strong>the</strong> quality of school infrastructure. There is<br />

a widespread view that children’s nutritional and<br />

health status before school age is a health policy<br />

matter. This silo mentality produces a distorted<br />

picture of policy priorities. Millions of children enter<br />

school having suffered irreparable damage to <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

learning potential as a result of malnutrition and<br />

micronutrient deficiencies. Poor maternal health<br />

and risks during pregnancy and childbirth are<br />

important contributory factors. The upshot of public<br />

policy failure in <strong>the</strong> areas of nutrition and maternal<br />

and child health care is not just unnecessary<br />

human suffering, but also <strong>the</strong> erosion of benefits<br />

associated with investment in education and<br />

progress in getting children into school.<br />

Early childhood education<br />

programmes — a mixed record<br />

Learning starts in <strong>the</strong> home, as children manipulate<br />

objects and materials, explore <strong>the</strong> world around<br />

<strong>the</strong>m and develop language. During <strong>the</strong> crucial<br />

48