Chapter 2. Progress towards the EFA goals - Unesco

Chapter 2. Progress towards the EFA goals - Unesco

Chapter 2. Progress towards the EFA goals - Unesco

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

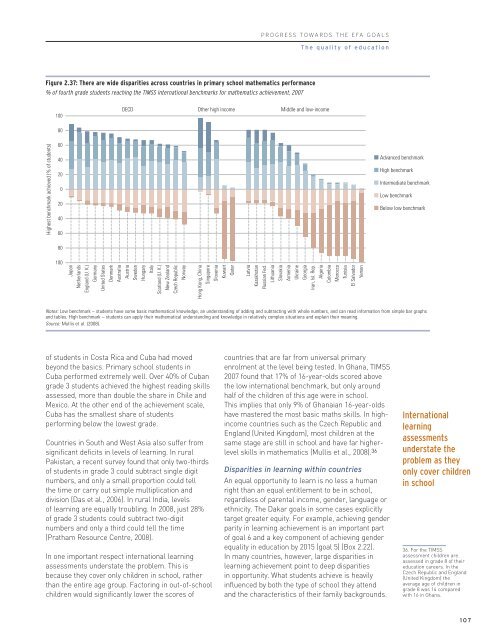

PROGRESS TOWARDS THE <strong>EFA</strong> GOALS<br />

The quality of education<br />

Figure <strong>2.</strong>37: There are wide disparities across countries in primary school ma<strong>the</strong>matics performance<br />

% of fourth grade students reaching <strong>the</strong> TIMSS international benchmarks for ma<strong>the</strong>matics achievement, 2007<br />

100<br />

OECD O<strong>the</strong>r high income Middle and low-income<br />

80<br />

Highest benchmark achieved (% of students)<br />

60<br />

40<br />

20<br />

0<br />

20<br />

40<br />

60<br />

Advanced benchmark<br />

High benchmark<br />

Intermediate benchmark<br />

Low benchmark<br />

Below low benchmark<br />

80<br />

100<br />

Japan<br />

Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands<br />

England (U. K.)<br />

Germany<br />

United States<br />

Denmark<br />

Australia<br />

Austria<br />

Sweden<br />

Hungary<br />

Italy<br />

Scotland (U. K.)<br />

New Zealand<br />

Czech Republic<br />

Norway<br />

Hong Kong, China<br />

Singapore<br />

Slovenia<br />

Kuwait<br />

Qatar<br />

Latvia<br />

Kazakhstan<br />

Russian Fed.<br />

Lithuania<br />

Slovakia<br />

Armenia<br />

Ukraine<br />

Georgia<br />

Iran, Isl. Rep.<br />

Algeria<br />

Colombia<br />

Morocco<br />

Tunisia<br />

El Salvador<br />

Yemen<br />

Notes: Low benchmark – students have some basic ma<strong>the</strong>matical knowledge, an understanding of adding and subtracting with whole numbers, and can read information from simple bar graphs<br />

and tables. High benchmark – students can apply <strong>the</strong>ir ma<strong>the</strong>matical understanding and knowledge in relatively complex situations and explain <strong>the</strong>ir meaning.<br />

Source: Mullis et al. (2008).<br />

of students in Costa Rica and Cuba had moved<br />

beyond <strong>the</strong> basics. Primary school students in<br />

Cuba performed extremely well. Over 40% of Cuban<br />

grade 3 students achieved <strong>the</strong> highest reading skills<br />

assessed, more than double <strong>the</strong> share in Chile and<br />

Mexico. At <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r end of <strong>the</strong> achievement scale,<br />

Cuba has <strong>the</strong> smallest share of students<br />

performing below <strong>the</strong> lowest grade.<br />

Countries in South and West Asia also suffer from<br />

significant deficits in levels of learning. In rural<br />

Pakistan, a recent survey found that only two-thirds<br />

of students in grade 3 could subtract single digit<br />

numbers, and only a small proportion could tell<br />

<strong>the</strong> time or carry out simple multiplication and<br />

division (Das et al., 2006). In rural India, levels<br />

of learning are equally troubling. In 2008, just 28%<br />

of grade 3 students could subtract two-digit<br />

numbers and only a third could tell <strong>the</strong> time<br />

(Pratham Resource Centre, 2008).<br />

In one important respect international learning<br />

assessments understate <strong>the</strong> problem. This is<br />

because <strong>the</strong>y cover only children in school, ra<strong>the</strong>r<br />

than <strong>the</strong> entire age group. Factoring in out-of-school<br />

children would significantly lower <strong>the</strong> scores of<br />

countries that are far from universal primary<br />

enrolment at <strong>the</strong> level being tested. In Ghana, TIMSS<br />

2007 found that 17% of 16-year-olds scored above<br />

<strong>the</strong> low international benchmark, but only around<br />

half of <strong>the</strong> children of this age were in school.<br />

This implies that only 9% of Ghanaian 16-year-olds<br />

have mastered <strong>the</strong> most basic maths skills. In highincome<br />

countries such as <strong>the</strong> Czech Republic and<br />

England (United Kingdom), most children at <strong>the</strong><br />

same stage are still in school and have far higherlevel<br />

skills in ma<strong>the</strong>matics (Mullis et al., 2008). 36<br />

Disparities in learning within countries<br />

An equal opportunity to learn is no less a human<br />

right than an equal entitlement to be in school,<br />

regardless of parental income, gender, language or<br />

ethnicity. The Dakar <strong>goals</strong> in some cases explicitly<br />

target greater equity. For example, achieving gender<br />

parity in learning achievement is an important part<br />

of goal 6 and a key component of achieving gender<br />

equality in education by 2015 (goal 5) (Box <strong>2.</strong>22).<br />

In many countries, however, large disparities in<br />

learning achievement point to deep disparities<br />

in opportunity. What students achieve is heavily<br />

influenced by both <strong>the</strong> type of school <strong>the</strong>y attend<br />

and <strong>the</strong> characteristics of <strong>the</strong>ir family backgrounds.<br />

International<br />

learning<br />

assessments<br />

understate <strong>the</strong><br />

problem as <strong>the</strong>y<br />

only cover children<br />

in school<br />

36. For <strong>the</strong> TIMSS<br />

assessment children are<br />

assessed in grade 8 of <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

education careers. In <strong>the</strong><br />

Czech Republic and England<br />

(United Kingdom) <strong>the</strong><br />

average age of children in<br />

grade 8 was 14 compared<br />

with 16 in Ghana.<br />

107