Chapter 2. Progress towards the EFA goals - Unesco

Chapter 2. Progress towards the EFA goals - Unesco

Chapter 2. Progress towards the EFA goals - Unesco

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

0<br />

0<br />

1<br />

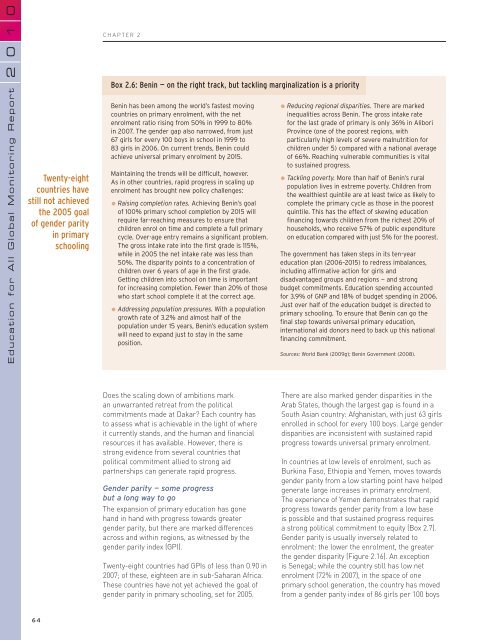

CHAPTER 2<br />

2<br />

Education for All Global Monitoring Report<br />

Twenty-eight<br />

countries have<br />

still not achieved<br />

<strong>the</strong> 2005 goal<br />

of gender parity<br />

in primary<br />

schooling<br />

Box <strong>2.</strong>6: Benin — on <strong>the</strong> right track, but tackling marginalization is a priority<br />

Benin has been among <strong>the</strong> world’s fastest moving<br />

countries on primary enrolment, with <strong>the</strong> net<br />

enrolment ratio rising from 50% in 1999 to 80%<br />

in 2007. The gender gap also narrowed, from just<br />

67 girls for every 100 boys in school in 1999 to<br />

83 girls in 2006. On current trends, Benin could<br />

achieve universal primary enrolment by 2015.<br />

Maintaining <strong>the</strong> trends will be difficult, however.<br />

As in o<strong>the</strong>r countries, rapid progress in scaling up<br />

enrolment has brought new policy challenges:<br />

Raising completion rates. Achieving Benin’s goal<br />

of 100% primary school completion by 2015 will<br />

require far-reaching measures to ensure that<br />

children enrol on time and complete a full primary<br />

cycle. Over-age entry remains a significant problem.<br />

The gross intake rate into <strong>the</strong> first grade is 115%,<br />

while in 2005 <strong>the</strong> net intake rate was less than<br />

50%. The disparity points to a concentration of<br />

children over 6 years of age in <strong>the</strong> first grade.<br />

Getting children into school on time is important<br />

for increasing completion. Fewer than 20% of those<br />

who start school complete it at <strong>the</strong> correct age.<br />

Addressing population pressures. With a population<br />

growth rate of 3.2% and almost half of <strong>the</strong><br />

population under 15 years, Benin’s education system<br />

will need to expand just to stay in <strong>the</strong> same<br />

position.<br />

Reducing regional disparities. There are marked<br />

inequalities across Benin. The gross intake rate<br />

for <strong>the</strong> last grade of primary is only 36% in Alibori<br />

Province (one of <strong>the</strong> poorest regions, with<br />

particularly high levels of severe malnutrition for<br />

children under 5) compared with a national average<br />

of 66%. Reaching vulnerable communities is vital<br />

to sustained progress.<br />

Tackling poverty. More than half of Benin’s rural<br />

population lives in extreme poverty. Children from<br />

<strong>the</strong> wealthiest quintile are at least twice as likely to<br />

complete <strong>the</strong> primary cycle as those in <strong>the</strong> poorest<br />

quintile. This has <strong>the</strong> effect of skewing education<br />

financing <strong>towards</strong> children from <strong>the</strong> richest 20% of<br />

households, who receive 57% of public expenditure<br />

on education compared with just 5% for <strong>the</strong> poorest.<br />

The government has taken steps in its ten-year<br />

education plan (2006–2015) to redress imbalances,<br />

including affirmative action for girls and<br />

disadvantaged groups and regions — and strong<br />

budget commitments. Education spending accounted<br />

for 3.9% of GNP and 18% of budget spending in 2006.<br />

Just over half of <strong>the</strong> education budget is directed to<br />

primary schooling. To ensure that Benin can go <strong>the</strong><br />

final step <strong>towards</strong> universal primary education,<br />

international aid donors need to back up this national<br />

financing commitment.<br />

Sources: World Bank (2009g); Benin Government (2008).<br />

Does <strong>the</strong> scaling down of ambitions mark<br />

an unwarranted retreat from <strong>the</strong> political<br />

commitments made at Dakar? Each country has<br />

to assess what is achievable in <strong>the</strong> light of where<br />

it currently stands, and <strong>the</strong> human and financial<br />

resources it has available. However, <strong>the</strong>re is<br />

strong evidence from several countries that<br />

political commitment allied to strong aid<br />

partnerships can generate rapid progress.<br />

Gender parity — some progress<br />

but a long way to go<br />

The expansion of primary education has gone<br />

hand in hand with progress <strong>towards</strong> greater<br />

gender parity, but <strong>the</strong>re are marked differences<br />

across and within regions, as witnessed by <strong>the</strong><br />

gender parity index (GPI).<br />

Twenty-eight countries had GPIs of less than 0.90 in<br />

2007; of <strong>the</strong>se, eighteen are in sub-Saharan Africa.<br />

These countries have not yet achieved <strong>the</strong> goal of<br />

gender parity in primary schooling, set for 2005.<br />

There are also marked gender disparities in <strong>the</strong><br />

Arab States, though <strong>the</strong> largest gap is found in a<br />

South Asian country: Afghanistan, with just 63 girls<br />

enrolled in school for every 100 boys. Large gender<br />

disparities are inconsistent with sustained rapid<br />

progress <strong>towards</strong> universal primary enrolment.<br />

In countries at low levels of enrolment, such as<br />

Burkina Faso, Ethiopia and Yemen, moves <strong>towards</strong><br />

gender parity from a low starting point have helped<br />

generate large increases in primary enrolment.<br />

The experience of Yemen demonstrates that rapid<br />

progress <strong>towards</strong> gender parity from a low base<br />

is possible and that sustained progress requires<br />

a strong political commitment to equity (Box <strong>2.</strong>7).<br />

Gender parity is usually inversely related to<br />

enrolment: <strong>the</strong> lower <strong>the</strong> enrolment, <strong>the</strong> greater<br />

<strong>the</strong> gender disparity (Figure <strong>2.</strong>16). An exception<br />

is Senegal; while <strong>the</strong> country still has low net<br />

enrolment (72% in 2007), in <strong>the</strong> space of one<br />

primary school generation, <strong>the</strong> country has moved<br />

from a gender parity index of 86 girls per 100 boys<br />

64