Chapter 2. Progress towards the EFA goals - Unesco

Chapter 2. Progress towards the EFA goals - Unesco

Chapter 2. Progress towards the EFA goals - Unesco

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

1<br />

2<br />

0<br />

0<br />

CHAPTER 2<br />

Education for All Global Monitoring Report<br />

In Pakistan,<br />

only around<br />

one-third of poor<br />

girls are in school<br />

Box <strong>2.</strong>8: Pakistan — gender disparities hold back progress<br />

Pakistan is off track for achieving universal primary<br />

education by 2015. The country accounts for a<br />

significant share of <strong>the</strong> global out-of-school problem.<br />

Failure to tackle gender disadvantages that intersect<br />

with poverty and regional differences is at <strong>the</strong> heart<br />

of <strong>the</strong> problem.<br />

Deep disparities based on location and wealth are<br />

a feature of education in Pakistan. In <strong>the</strong> richest<br />

households, over 85% of children go to primary<br />

school, with little difference between boys and girls.<br />

Attendance rates for children from poor households<br />

are far lower, especially for females: only around onethird<br />

of poor girls are in school. Similarly, attendance<br />

is higher and <strong>the</strong> gender gap smaller in urban areas<br />

than in rural ones, and in <strong>the</strong> relatively wealthy Punjab<br />

province than in Balochistan and Sindh (Figure <strong>2.</strong>19).<br />

The North West Frontier Province stands out as<br />

having above average attendance for boys but well<br />

below average attendance for girls. There is growing<br />

concern that this gender gap could be widening<br />

fur<strong>the</strong>r. In <strong>the</strong> Taliban-occupied parts of <strong>the</strong> province,<br />

91 girls’ schools have been destroyed and<br />

25 damaged, with some boys’ schools also suffering.<br />

The factors behind Pakistan’s deep gender disparities<br />

have been extensively researched. Distance to school<br />

matters far more for girls than boys, reflecting<br />

security concerns and household labour demands.<br />

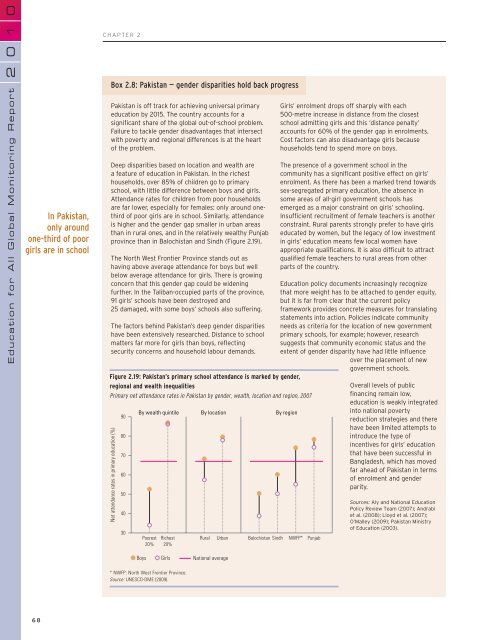

Figure <strong>2.</strong>19: Pakistan’s primary school attendance is marked by gender,<br />

regional and wealth inequalities<br />

Primary net attendance rates in Pakistan by gender, wealth, location and region, 2007<br />

Net attendance rates in primary education (%)<br />

90<br />

80<br />

70<br />

60<br />

50<br />

40<br />

30<br />

By wealth quintile By location By region<br />

Poorest<br />

20%<br />

Richest<br />

20%<br />

Rural<br />

Urban<br />

Balochistan Sindh<br />

Girls’ enrolment drops off sharply with each<br />

500-metre increase in distance from <strong>the</strong> closest<br />

school admitting girls and this ‘distance penalty’<br />

accounts for 60% of <strong>the</strong> gender gap in enrolments.<br />

Cost factors can also disadvantage girls because<br />

households tend to spend more on boys.<br />

The presence of a government school in <strong>the</strong><br />

community has a significant positive effect on girls’<br />

enrolment. As <strong>the</strong>re has been a marked trend <strong>towards</strong><br />

sex-segregated primary education, <strong>the</strong> absence in<br />

some areas of all-girl government schools has<br />

emerged as a major constraint on girls’ schooling.<br />

Insufficient recruitment of female teachers is ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

constraint. Rural parents strongly prefer to have girls<br />

educated by women, but <strong>the</strong> legacy of low investment<br />

in girls’ education means few local women have<br />

appropriate qualifications. It is also difficult to attract<br />

qualified female teachers to rural areas from o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

parts of <strong>the</strong> country.<br />

Education policy documents increasingly recognize<br />

that more weight has to be attached to gender equity,<br />

but it is far from clear that <strong>the</strong> current policy<br />

framework provides concrete measures for translating<br />

statements into action. Policies indicate community<br />

needs as criteria for <strong>the</strong> location of new government<br />

primary schools, for example; however, research<br />

suggests that community economic status and <strong>the</strong><br />

extent of gender disparity have had little influence<br />

over <strong>the</strong> placement of new<br />

government schools.<br />

NWFP*<br />

Punjab<br />

Overall levels of public<br />

financing remain low,<br />

education is weakly integrated<br />

into national poverty<br />

reduction strategies and <strong>the</strong>re<br />

have been limited attempts to<br />

introduce <strong>the</strong> type of<br />

incentives for girls’ education<br />

that have been successful in<br />

Bangladesh, which has moved<br />

far ahead of Pakistan in terms<br />

of enrolment and gender<br />

parity.<br />

Sources: Aly and National Education<br />

Policy Review Team (2007); Andrabi<br />

et al. (2008); Lloyd et al. (2007);<br />

O’Malley (2009); Pakistan Ministry<br />

of Education (2003).<br />

Boys<br />

Girls<br />

National average<br />

* NWFP: North West Frontier Province.<br />

Source: UNESCO-DME (2009).<br />

68