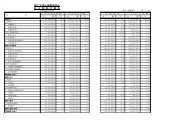

Journal of Film Preservation - FIAF

Journal of Film Preservation - FIAF

Journal of Film Preservation - FIAF

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

du cinéma muet, ce curieux mélange<br />

de didactisme, de reconstitution<br />

et d’images érotiques où le diable,<br />

interprété par Christensen lui-même,<br />

intervient au besoin, en a longtemps<br />

fait un objet de scandale. Avec le recul<br />

le film apparaît comme une œuvre<br />

exceptionnellement originale et<br />

novatrice.<br />

Préparé sous la direction de Jon<br />

Wengström, conservateur film du<br />

Swedish <strong>Film</strong> Institute, ce c<strong>of</strong>fret<br />

constitue un travail exemplaire<br />

de conservation, préservation et<br />

restauration de haut niveau. Les<br />

procédés de couleur originaux sont<br />

respectés et chaque film a fait l’objet<br />

d’une partition musicale nouvelle<br />

de Matti Bye. Tous les films ont<br />

des intertitres suédois et français;<br />

plusieurs proposent même des titres<br />

en français, allemand, espagnol, italien<br />

et portugais. Enfin chaque film est<br />

accompagné d’un livret de très belle<br />

tenue comprenant des essais, des notes<br />

biographiques et des détails sur sa<br />

restauration.<br />

Ce précieux c<strong>of</strong>fret est d’ores et déjà un<br />

objet de collection : à quand une suite?<br />

Terje Vigen, Victor Sjöström, 1917.<br />

<strong>Film</strong> history has perhaps been less kind to Mauritz Stiller, who gets the<br />

lion’s share <strong>of</strong> the SFI’s box set with three <strong>of</strong> his peak-career films: Herr Arnes<br />

Pengar (Sir Arne’s Treasure, 1919), Erotikon (1920) and Gösta Berlings Saga<br />

(1924). Stiller is remembered principally as Greta Garbo’s Svengali, lured<br />

into taking her to Hollywood and then cruelly neglected and rejected.<br />

Again, it has taken the act <strong>of</strong> physical rehabilitation <strong>of</strong> his films to show<br />

his mature versatility and to restore him to the Pantheon <strong>of</strong> accomplished,<br />

innovative and influential film-makers <strong>of</strong> the silent era where he properly<br />

belongs. Pro<strong>of</strong> is in this trio <strong>of</strong> chefs d’oeuvre, which range from his two<br />

energetic adaptations <strong>of</strong> epic stories by Selma Lagerlöf, both <strong>of</strong> which<br />

glory in winter landscapes, to the stately, sophisticated comedy <strong>of</strong> manners<br />

and infidelity among the upper classes, Erotikon, a genre with which<br />

Stiller is more commonly associated, his sharp and amused view <strong>of</strong> “sexual<br />

interchange” in high society being compared favourably with Bergman’s<br />

social comedies, such as Sommarnattens Leende (Smiles <strong>of</strong> a Summer Night,<br />

1955). But it is clear from the juxtaposition <strong>of</strong> these three films that Stiller<br />

was at his best out <strong>of</strong> doors, amongst the Nordic landscape, showing<br />

Man coming to terms with Nature, his own and that <strong>of</strong> his surroundings;<br />

by comparison, his drawing-room films, though beautifully and ironically<br />

observed, appear indulgent and slow. It is equally apparent that Herr Arnes<br />

Pengar, a stirring spectacle about greedy Scottish mercenaries in wintry<br />

16th-century Sweden, is his supreme achievement and a film deserving <strong>of</strong><br />

wider recognition. Nevertheless, Garbo inevitably gets some prominence<br />

in this collection in relation to her breakthrough film, Gösta Berlings Saga,<br />

and a flurry <strong>of</strong> fascinating extras shows her, pretty, plump, gauche and<br />

outgoing, in what is left <strong>of</strong> an early feature, Luffar-Petter (Peter the Tramp,<br />

1922), and some Stockholm commercials – and later, now a Hollywood star<br />

and global celebrity, looking nervous and introverted on board ship in a<br />

1929 newsreel.<br />

What, then, <strong>of</strong> the sixth title in this collection <strong>of</strong><br />

Swedish classics, Benjamin Christensen’s Häxan<br />

(Witchcraft Through the Ages, 1922), which seems<br />

to sit awkwardly alongside the more venerated<br />

work <strong>of</strong> Sjöström and Stiller? In fact, it is in<br />

retrospect the most original and innovative <strong>of</strong><br />

all the Swedish films made in this period. Older<br />

cinéphiles will remember it as a faithful repertory<br />

warhorse on the arthouse circuit in the 1960s<br />

and 70s, when its quasi-documentary style still<br />

looked startlingly novel and its Satanic theme<br />

quite shocking, but a film largely neglected since<br />

– which makes it all the riper for re-appraisal.<br />

The only film <strong>of</strong> Danish director Christensen to<br />

become widely known outside Scandinavia, it is<br />

an odd mixture <strong>of</strong> didactic lectures, suggestive<br />

dramatic recreations and erotic imagery, punctuated with scenes <strong>of</strong> nudity<br />

and torture, purporting to explain medieval perceptions <strong>of</strong> witchcraft, with<br />

Christensen himself playing the devil. Unsurprisingly, the film was cut by<br />

the censors and condemned by the Catholic church, and it failed at the box<strong>of</strong>fice.<br />

It remains unique in silent cinema, and a singular testament to the<br />

artistic freedom (and generous budgets) which Swedish cinema enjoyed<br />

during its “golden years” and which spawned so many masterpieces.<br />

80 <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Film</strong> <strong>Preservation</strong> / 81 / 2009