- Page 2 and 3: A Textbook of Clinical Pharmacology

- Page 4 and 5: A Textbook of Clinical Pharmacology

- Page 6 and 7: This fifth edition is dedicated to

- Page 8 and 9: CONTENTS FOREWORD PREFACE ACKNOWLED

- Page 10 and 11: PREFACE Clinical pharmacology is th

- Page 12 and 13: PART I GENERAL PRINCIPLES

- Page 14 and 15: CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION TO THERAPEUT

- Page 16 and 17: SCIENTIFIC BASIS OF USE OF DRUGS IN

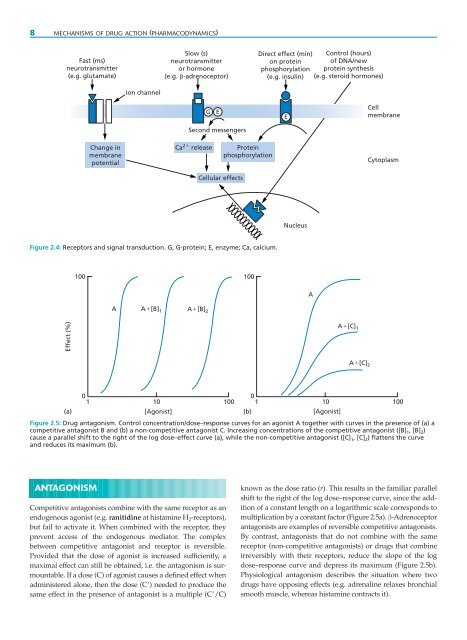

- Page 20 and 21: SLOW PROCESSES 9 100 2 Dose ratio -

- Page 22 and 23: CHAPTER 3 PHARMACOKINETICS ● Intr

- Page 24 and 25: REPEATED (MULTIPLE) DOSING 13 In re

- Page 26 and 27: NON-LINEAR (‘DOSE-DEPENDENT’) P

- Page 28 and 29: CHAPTER 4 DRUG ABSORPTION AND ROUTE

- Page 30 and 31: ROUTES OF ADMINISTRATION 19 ROUTES

- Page 32 and 33: ROUTES OF ADMINISTRATION 21 Transde

- Page 34 and 35: ROUTES OF ADMINISTRATION 23 FURTHER

- Page 36 and 37: PHASE II METABOLISM (TRANSFERASE RE

- Page 38 and 39: ENZYME INDUCTION 27 and lorazepam.

- Page 40 and 41: METABOLISM OF DRUGS BY INTESTINAL O

- Page 42 and 43: CHAPTER 6 RENAL EXCRETION OF DRUGS

- Page 44 and 45: ACTIVE TUBULAR REABSORPTION 33 ACTI

- Page 46 and 47: RENAL DISEASE 35 DISTRIBUTION Drug

- Page 48 and 49: LIVER DISEASE 37 Detailed recommend

- Page 50 and 51: THYROID DISEASE 39 DIGOXIN Myxoedem

- Page 52 and 53: CHAPTER 8 THERAPEUTIC DRUG MONITORI

- Page 54 and 55: DRUGS FOR WHICH THERAPEUTIC DRUG MO

- Page 56 and 57: CHAPTER 9 DRUGS IN PREGNANCY ● In

- Page 58 and 59: PHARMACOKINETICS IN PREGNANCY 47 va

- Page 60 and 61: PRESCRIBING IN PREGNANCY 49 an anti

- Page 62 and 63: PRESCRIBING IN PREGRANCY 51 Case hi

- Page 64 and 65: BREAST-FEEDING 53 METABOLISM At bir

- Page 66 and 67: RESEARCH 55 lifelong effects as a r

- Page 68 and 69:

PHARMACODYNAMIC CHANGES 57 DISTRIBU

- Page 70 and 71:

EFFECT OF DRUGS ON SOME MAJOR ORGAN

- Page 72 and 73:

RESEARCH 61 FURTHER READING Dhesi J

- Page 74 and 75:

ADVERSE DRUG REACTION MONITORING/SU

- Page 76 and 77:

ADVERSE DRUG REACTION MONITORING/SU

- Page 78 and 79:

PREVENTION OF ALLERGIC DRUG REACTIO

- Page 80 and 81:

EXAMPLES OF ALLERGIC AND OTHER ADVE

- Page 82 and 83:

CHAPTER 13 DRUG INTERACTIONS ● In

- Page 84 and 85:

HARMFUL INTERACTIONS 73 Response Re

- Page 86 and 87:

HARMFUL INTERACTIONS 75 Table 13.1:

- Page 88 and 89:

HARMFUL INTERACTIONS 77 Table 13.5:

- Page 90 and 91:

CHAPTER 14 PHARMACOGENETICS ● Int

- Page 92 and 93:

GENETIC INFLUENCES ON DRUG METABOLI

- Page 94 and 95:

INHERITED DISEASES THAT PREDISPOSE

- Page 96 and 97:

INHERITED DISEASES THAT PREDISPOSE

- Page 98 and 99:

CLINICAL TRIALS 87 • Discovery

- Page 100 and 101:

CLINICAL DRUG DEVELOPMENT 89 Too ma

- Page 102 and 103:

GLOBALIZATION 91 ETHICS COMMITTEES

- Page 104 and 105:

CELL-BASED AND RECOMBINANT DNA THER

- Page 106 and 107:

HUMAN STEM CELL THERAPY 95 duration

- Page 108 and 109:

CHAPTER 17 ALTERNATIVE MEDICINES: H

- Page 110 and 111:

SOY 99 A case report has suggested

- Page 112 and 113:

MISCELLANEOUS HERBS 101 including h

- Page 114 and 115:

PART II THE NERVOUS SYSTEM

- Page 116 and 117:

CHAPTER 18 HYPNOTICS AND ANXIOLYTIC

- Page 118 and 119:

ANXIETY 107 and daytime sleeping sh

- Page 120 and 121:

ANXIETY 109 Key points • Insomnia

- Page 122 and 123:

SCHIZOPHRENIA 111 Box 19.1: Dopamin

- Page 124 and 125:

SCHIZOPHRENIA 113 The Boston Collab

- Page 126 and 127:

BEHAVIOURAL EMERGENCIES 115 Oral me

- Page 128 and 129:

DEPRESSIVE ILLNESSES AND ANTIDEPRES

- Page 130 and 131:

DEPRESSIVE ILLNESSES AND ANTIDEPRES

- Page 132 and 133:

LITHIUM, TRYPTOPHAN AND ST JOHN’S

- Page 134 and 135:

SPECIAL GROUPS 123 Case history A 4

- Page 136 and 137:

PARKINSON’S SYNDROME AND ITS TREA

- Page 138 and 139:

PARKINSON’S SYNDROME AND ITS TREA

- Page 140 and 141:

MYASTHENIA GRAVIS 129 CHOREA The γ

- Page 142 and 143:

ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE 131 Cholinerg

- Page 144 and 145:

CHAPTER 22 ANTI-EPILEPTICS ● Intr

- Page 146 and 147:

GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF TREATMENT OF

- Page 148 and 149:

GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF TREATMENT OF

- Page 150 and 151:

WITHDRAWAL OF ANTI-EPILEPTIC DRUGS

- Page 152 and 153:

FEBRILE CONVULSIONS 141 Case histor

- Page 154 and 155:

DRUGS USED FOR MIGRAINE PROPHYLAXIS

- Page 156 and 157:

CHAPTER 24 ANAESTHETICS AND MUSCLE

- Page 158 and 159:

INHALATIONAL ANAESTHETICS 147 is th

- Page 160 and 161:

SUPPLEMENTARY DRUGS 149 • Respira

- Page 162 and 163:

MUSCLE RELAXANTS 151 NON-DEPOLARIZI

- Page 164 and 165:

LOCAL ANAESTHETICS 153 have also pr

- Page 166 and 167:

CHAPTER 25 ANALGESICS AND THE CONTR

- Page 168 and 169:

DRUGS USED TO TREAT MILD OR MODERAT

- Page 170 and 171:

OPIOIDS 159 Key points Drugs for mi

- Page 172 and 173:

OPIOIDS 161 increases, correlating

- Page 174 and 175:

MANAGEMENT OF POST-OPERATIVE PAIN 1

- Page 176 and 177:

PART III THE MUSCULOSKELETAL SYSTEM

- Page 178 and 179:

CHAPTER 26 ANTI-INFLAMMATORY DRUGS

- Page 180 and 181:

DISEASE-MODIFYING ANTIRHEUMATIC DRU

- Page 182 and 183:

HYPERURICAEMIA AND GOUT 171 • Sto

- Page 184 and 185:

HYPERURICAEMIA AND GOUT 173 Pharmac

- Page 186 and 187:

PART IV THE CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM

- Page 188 and 189:

CHAPTER 27 PREVENTION OF ATHEROMA:

- Page 190 and 191:

PREVENTION OF ATHEROMA 179 responsi

- Page 192 and 193:

DRUGS USED TO TREAT DYSLIPIDAEMIA 1

- Page 194 and 195:

DRUGS USED TO TREAT DYSLIPIDAEMIA 1

- Page 196 and 197:

CHAPTER 28 HYPERTENSION ● Introdu

- Page 198 and 199:

DRUGS USED TO TREAT HYPERTENSION 18

- Page 200 and 201:

DRUGS USED TO TREAT HYPERTENSION 18

- Page 202 and 203:

DRUGS USED TO TREAT HYPERTENSION 19

- Page 204 and 205:

OTHER ANTIHYPERTENSIVE DRUGS 193 Ke

- Page 206 and 207:

OTHER ANTIHYPERTENSIVE DRUGS 195 Ca

- Page 208 and 209:

MANAGEMENT OF STABLE ANGINA 197 Ass

- Page 210 and 211:

MANAGEMENT OF UNSTABLE CORONARY DIS

- Page 212 and 213:

DRUGS USED IN ISCHAEMIC HEART DISEA

- Page 214 and 215:

DRUGS USED IN ISCHAEMIC HEART DISEA

- Page 216 and 217:

ANTICOAGULANTS 205 Intrinsic pathwa

- Page 218 and 219:

ANTICOAGULANTS 207 that the pharmac

- Page 220 and 221:

ANTICOAGULANTS IN PREGNANCY AND PUE

- Page 222 and 223:

CHAPTER 31 HEART FAILURE ● Introd

- Page 224 and 225:

DRUGS FOR HEART FAILURE 213 The dru

- Page 226 and 227:

DRUGS FOR HEART FAILURE 215 therape

- Page 228 and 229:

CHAPTER 32 CARDIAC DYSRHYTHMIAS ●

- Page 230 and 231:

CARDIOPULMONARY RESUSCITATION AND C

- Page 232 and 233:

TREATMENT OF OTHER SPECIFIC DYSRHYT

- Page 234 and 235:

SELECTED ANTI-DYSRHYTHMIC DRUGS 223

- Page 236 and 237:

SELECTED ANTI-DYSRHYTHMIC DRUGS 225

- Page 238 and 239:

SELECTED ANTI-DYSRHYTHMIC DRUGS 227

- Page 240 and 241:

SELECTED ANTI-DYSRHYTHMIC DRUGS 229

- Page 242 and 243:

PART V THE RESPIRATORY SYSTEM

- Page 244 and 245:

CHAPTER 33 THERAPY OF ASTHMA, CHRON

- Page 246 and 247:

CHRONIC BRONCHITIS AND EMPHYSEMA 23

- Page 248 and 249:

DRUGS USED TO TREAT ASTHMA AND CHRO

- Page 250 and 251:

DRUGS USED TO TREAT ASTHMA AND CHRO

- Page 252 and 253:

RESPIRATORY FAILURE 241 use in asth

- Page 254 and 255:

DRUG-INDUCED PULMONARY DISEASE 243

- Page 256 and 257:

PART VI THE ALIMENTARY SYSTEM

- Page 258 and 259:

CHAPTER 34 ALIMENTARY SYSTEM AND LI

- Page 260 and 261:

PEPTIC ULCERATION 249 • With rega

- Page 262 and 263:

PEPTIC ULCERATION 251 Ranitidine ha

- Page 264 and 265:

ANTI-EMETICS 253 Vestibular stimula

- Page 266 and 267:

INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE 255 cort

- Page 268 and 269:

CONSTIPATION 257 • in hepatocellu

- Page 270 and 271:

PANCREATIC INSUFFICIENCY 259 Ciprof

- Page 272 and 273:

LIVER DISEASE 261 withdrawal), smal

- Page 274 and 275:

DRUGS THAT MODIFY APPETITE 263 Tabl

- Page 276 and 277:

CHAPTER 35 VITAMINS AND TRACE ELEME

- Page 278 and 279:

VITAMIN C(ASCORBIC ACID) 267 dinucl

- Page 280 and 281:

TRACE ELEMENTS 269 Table 35.1: Comm

- Page 282 and 283:

PART VII FLUIDS AND ELECTROLYTES

- Page 284 and 285:

CHAPTER 36 NEPHROLOGICAL AND RELATE

- Page 286 and 287:

DIURETICS 275 Key points Diuretics

- Page 288 and 289:

VOLUME DEPLETION 277 is sometimes c

- Page 290 and 291:

DRUGS THAT AFFECT THE BLADDER AND G

- Page 292 and 293:

DRUGS THAT AFFECT THE BLADDER AND G

- Page 294 and 295:

PART VIII THE ENDOCRINE SYSTEM

- Page 296 and 297:

CHAPTER 37 DIABETES MELLITUS ● In

- Page 298 and 299:

DRUGS USED TO TREAT DIABETES MELLIT

- Page 300 and 301:

DRUGS USED TO TREAT DIABETES MELLIT

- Page 302 and 303:

DRUGS USED TO TREAT DIABETES MELLIT

- Page 304 and 305:

ANTITHYROID DRUGS 293 deficiency. P

- Page 306 and 307:

SPECIAL SITUATIONS 295 fertility. I

- Page 308 and 309:

CHAPTER 39 CALCIUM METABOLISM ● I

- Page 310 and 311:

BISPHOSPHONATES 299 effective in li

- Page 312 and 313:

CINACALCET 301 Further reading Bloc

- Page 314 and 315:

ADRENAL CORTEX 303 Table 40.1: Acti

- Page 316 and 317:

ADRENAL MEDULLA 305 injection may b

- Page 318 and 319:

CHAPTER 41 REPRODUCTIVE ENDOCRINOLO

- Page 320 and 321:

FEMALE REPRODUCTIVE ENDOCRINOLOGY 3

- Page 322 and 323:

FEMALE REPRODUCTIVE ENDOCRINOLOGY 3

- Page 324 and 325:

MALE REPRODUCTIVE ENDOCRINOLOGY 313

- Page 326 and 327:

MALE REPRODUCTIVE ENDOCRINOLOGY 315

- Page 328 and 329:

ANTERIOR PITUITARY HARMONES AND REL

- Page 330 and 331:

POSTERIOR PITUITARY HARMONES 319 FU

- Page 332 and 333:

PART IX SELECTIVE TOXICITY

- Page 334 and 335:

CHAPTER 43 ANTIBACTERIAL DRUGS ●

- Page 336 and 337:

COMMONLY PRESCRIBED ANTIBACTERIAL D

- Page 338 and 339:

COMMONLY PRESCRIBED ANTIBACTERIAL D

- Page 340 and 341:

COMMONLY PRESCRIBED ANTIBACTERIAL D

- Page 342 and 343:

COMMONLY PRESCRIBED ANTIBACTERIAL D

- Page 344 and 345:

COMMONLY PRESCRIBED ANTIBACTERIAL D

- Page 346 and 347:

PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT OF MYCOBAC

- Page 348 and 349:

FIRST-LINE DRUGS IN TUBERCULOSIS TH

- Page 350 and 351:

MYCOBACTERIUM LEPRAE INFECTION 339

- Page 352 and 353:

ANTIFUNGAL DRUG THERAPY 341 POLYENE

- Page 354 and 355:

ANTIFUNGAL DRUG THERAPY 343 therapy

- Page 356 and 357:

ANTIVIRAL DRUG THERAPY (EXCLUDING A

- Page 358 and 359:

ANTIVIRAL DRUG THERAPY (EXCLUDING A

- Page 360 and 361:

INTERFERONS AND ANTIVIRAL HEPATITIS

- Page 362 and 363:

CHAPTER 46 HIV AND AIDS ● Introdu

- Page 364 and 365:

ANTI-HIV DRUGS 353 Table 46.1: Exam

- Page 366 and 367:

ANTI-HIV DRUGS 355 NON-NUCLEOSIDE A

- Page 368 and 369:

OPPORTUNISTIC INFECTIONS IN HIV-1-S

- Page 370 and 371:

ANTI-HERPES VIRUS THERAPY 359 salva

- Page 372 and 373:

CHAPTER 47 MALARIA AND OTHER PARASI

- Page 374 and 375:

MALARIA 363 Pharmacokinetics Chloro

- Page 376 and 377:

HELMINTHIC INFECTION 365 Table 47.2

- Page 378 and 379:

CHAPTER 48 CANCER CHEMOTHERAPY ●

- Page 380 and 381:

COMMON COMPLICATIONS OF CANCER CHEM

- Page 382 and 383:

DRUGS USED IN CANCER CHEMOTHERAPY 3

- Page 384 and 385:

DRUGS USED IN CANCER CHEMOTHERAPY 3

- Page 386 and 387:

DRUGS USED IN CANCER CHEMOTHERAPY 3

- Page 388 and 389:

DRUGS USED IN CANCER CHEMOTHERAPY 3

- Page 390 and 391:

DRUGS USED IN CANCER CHEMOTHERAPY 3

- Page 392 and 393:

DRUGS USED IN CANCER CHEMOTHERAPY 3

- Page 394 and 395:

DRUGS USED IN CANCER CHEMOTHERAPY 3

- Page 396 and 397:

DRUGS USED IN CANCER CHEMOTHERAPY 3

- Page 398 and 399:

PART X HAEMATOLOGY

- Page 400 and 401:

CHAPTER 49 ANAEMIA AND OTHER HAEMAT

- Page 402 and 403:

HAEMATINICS - IRON, VITAMIN B 12 AN

- Page 404 and 405:

HAEMATOPOIETIC GROWTH FACTORS 393 S

- Page 406 and 407:

IDIOPATHIC THROMBOCYTOPENIC PURPURA

- Page 408 and 409:

PART XI IMMUNOPHARMACOLOGY

- Page 410 and 411:

CHAPTER 50 CLINICAL IMMUNOPHARMACOL

- Page 412 and 413:

IMMUNOSUPPRESSIVE AGENTS 401 Ag Ant

- Page 414 and 415:

IMMUNOSUPPRESSIVE AGENTS 403 Table

- Page 416 and 417:

CHEMICAL MEDIATORS OF THE IMMUNE RE

- Page 418 and 419:

IMMUNOGLOBULINS AS THERAPY 407 DRUG

- Page 420 and 421:

PART XII THE SKIN

- Page 422 and 423:

CHAPTER 51 DRUGS AND THE SKIN ● I

- Page 424 and 425:

DERMATITIS (ECZEMA) 413 Avoid preci

- Page 426 and 427:

PSORIASIS 415 Emollients Improving?

- Page 428 and 429:

ADVERSE DRUG REACTIONS INVOLVING TH

- Page 430 and 431:

ADVERSE DRUG REACTIONS INVOLVING TH

- Page 432 and 433:

PART XIII THE EYE

- Page 434 and 435:

CHAPTER 52 DRUGS AND THE EYE ● In

- Page 436 and 437:

DRUGS USED TO CONSTRICT THE PUPIL A

- Page 438 and 439:

DRUGS USED TO TREAT INFLAMMATORY DI

- Page 440 and 441:

CONTACT LENS WEARERS 429 Table 52.6

- Page 442 and 443:

PART XIV CLINICAL TOXICOLOGY

- Page 444 and 445:

CHAPTER 53 DRUGS AND ALCOHOL ABUSE

- Page 446 and 447:

OPIOID/NARCOTIC ANALGESICS 435 Tabl

- Page 448 and 449:

DRUGS THAT ALTER PERCEPTION 437 whi

- Page 450 and 451:

CENTRAL DEPRESSANTS 439 Peak plasma

- Page 452 and 453:

CENTRAL DEPRESSANTS 441 Key points

- Page 454 and 455:

MISCELLANEOUS 443 FURTHER READING G

- Page 456 and 457:

INTENTIONAL SELF-POISONING 445 Tabl

- Page 458 and 459:

INTENTIONAL SELF-POISONING 447 Tabl

- Page 460 and 461:

CRIMINAL POISONING 449 Commission o

- Page 462 and 463:

INDEX Note: Page numbers in italics

- Page 464 and 465:

INDEX 453 atrial fibrillation 217,

- Page 466 and 467:

INDEX 455 Cushing’s syndrome 302

- Page 468 and 469:

INDEX 457 5-fluorouracil 375-6 fluo

- Page 470 and 471:

INDEX 459 children 54 diazepam 108

- Page 472 and 473:

INDEX 461 non-steroidal anti-inflam

- Page 474 and 475:

INDEX 463 puberty (male), delay 314

- Page 476:

INDEX 465 tolerance 9, 433 benzodia