CONSERVATIVE

eurocon_12_2015_summer-fall

eurocon_12_2015_summer-fall

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

This became still more the case in the state of<br />

Dubrovnik, whose major preoccupation throughout<br />

its existence was to ensure that no individual or clique<br />

became too powerful.<br />

This is one reason, incidentally, why the<br />

picture we have of so many Ragusans is rather grey.<br />

Conformity, uniformity, and equality—at least among<br />

the noble patricians who ran the state’s affairs—were<br />

emphasised. Decisions were collective wherever<br />

possible. The only Ragusan citizen to have a statue<br />

erected in his honour—in this case a rather uninspiring<br />

bust in the courtyard of the Rector’s Palace—was<br />

Miho Pracat. He was a commoner, a hugely wealthy<br />

merchant from Lopud, and great civic philanthropist.<br />

And even then the Ragusan Senate wrangled for years<br />

before it agreed to commission the work. This attitude<br />

was part of the Venetian legacy.<br />

Hungary<br />

The final stage of Dubrovnik’s political<br />

development towards an autonomy, which can<br />

reasonably be described as independence, was made<br />

under Hungarian allegiance. Having been routed in<br />

their war with Hungary, the Venetians left Dubrovnik<br />

for good in 1358.<br />

The Dubrovnik patriciate now managed, by an<br />

extraordinarily skilful use of diplomacy and influence,<br />

to secure terms of submission to the Hungarian King<br />

which were unique in Dalmatia. Dubrovnik could<br />

choose its own Rector (as the Count began now to be<br />

called) from among its own citizens. It conducted its<br />

own foreign policy. It minted its own coinage.<br />

True, it flew the Hungarian flag and employed<br />

Hungarian guards—called barabanti—to guard its<br />

fortresses. It also paid a modest tribute, undertook<br />

to assist the Hungarians in certain circumstances, and<br />

honoured the Hungarian King with laudes chanted in<br />

the cathedral. But for all practical purposes Dubrovnik<br />

was its own master. The city then acquired its splendid<br />

coat of arms.<br />

Dubrovnik also undertook further territorial<br />

expansion. In later years, Dubrovnik made much of<br />

its peaceful instincts, its preference for diplomacy over<br />

war, its interest in commerce not aggrandisement. But<br />

these were really typical Ragusan attempts to make a<br />

virtue of necessity once the arrival of the Ottoman<br />

Empire transformed the military situation in the<br />

Balkans. Whenever they could, the Ragusans grabbed<br />

quite shamelessly, and quite successfully too.<br />

The Ottomans<br />

The Turkish-Ragusan relationship is surely one<br />

of the most remarkable symbioses to be found in<br />

European history. Dubrovnik began tentative dealings<br />

with the Ottoman invaders from the late 14th century,<br />

but it strenuously sought to avoid paying tribute to the<br />

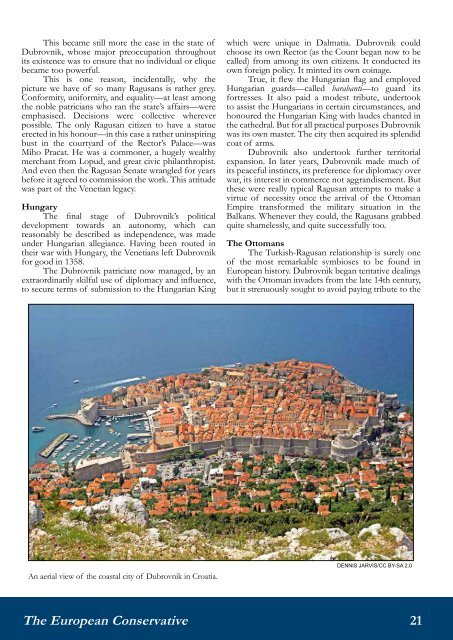

An aerial view of the coastal city of Dubrovnik in Croatia.<br />

DENNIS JARVIS/CC BY-SA 2.0<br />

The European Conservative 21