CONSERVATIVE

eurocon_12_2015_summer-fall

eurocon_12_2015_summer-fall

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Roman Joch<br />

A Literary Love<br />

Roger Scruton, who celebrated his 70th birthday<br />

last year, is a philosopher, farmer, and a gentleman. He<br />

resides on his farm near the town of Malmesbury in the<br />

southwest of England. This fact has inspired some to<br />

refer to him as “the philosopher from Malmesbury”—<br />

which should remind us that there once was another<br />

well-known philosopher in the same town (but of very<br />

different views): Thomas Hobbes.<br />

Originally a professor of aesthetics, Scruton<br />

has authored forty books dealing with vastly different<br />

subjects—ranging from the aesthetics of architecture,<br />

music, wine, and environmentalism, to modern<br />

philosophy, the New Left, sexual desire, God, and fox<br />

hunting. He has also composed two operas, developed<br />

a TV series for the BBC (on the idea of beauty), and<br />

has written several novels (including The Disappeared,<br />

which appeared earlier this year).<br />

His acclaimed 200-page novel, Notes from<br />

Underground, was published last year. It deals with<br />

many interrelated topics: love, nostalgia, life under<br />

totalitarian rule in Prague during the 1980s, the lives<br />

of dissidents, the sacred, human dignity, striving for<br />

meaningful existence, faith, betrayal, disappointment,<br />

and the unfulfilled promises of the changes that<br />

occurred in November 1989.<br />

The book is about the love that Scruton has<br />

for the city of Prague and the Czech language. It is<br />

also incredibly lyrical, with purposefully ambivalent<br />

language and formulations, leaving much—including<br />

the climax—open to the reader’s imagination.<br />

Scruton is a fitting person for the job of writing<br />

a book about life in Prague thirty years ago, since<br />

between 1979 and 1989 he actively assisted Czech<br />

dissidents, helping to smuggle censored books into<br />

the country and recruiting Western lecturers for illegal<br />

seminars of an “underground university”. (These were<br />

typically held in private apartments.) Between 1979<br />

and 1985, he visited the country frequently—until his<br />

arrest by Communist State Security officials and his<br />

subsequent—and, at the time, irrevocable—expulsion<br />

from the country.<br />

He returned only after the fall of Communism<br />

in 1990 and held his first public lecture (in the town<br />

of Brno) in which he called for authorities to ban the<br />

Communist Party. For his contributions to the cause of<br />

freedom in the Czech Republic, Scruton was awarded<br />

a Medal of Merit of the 1st Class, by the late Czech<br />

president, Václav Havel.<br />

Notes from Underground is inspired by many of these<br />

experiences. It is written in the form of a retrospective<br />

from the point of view of the main character, Jan<br />

Reichl, who, while sitting at his university office in<br />

Washington, D.C., reminisces about the life he led as a<br />

former political dissident.<br />

Jan was not allowed to attend university. His<br />

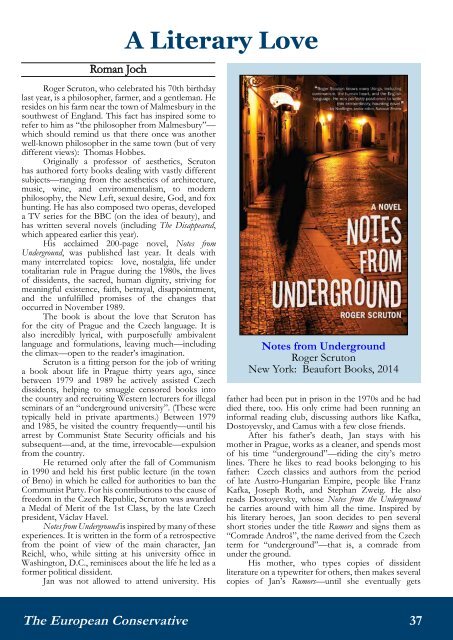

Notes from Underground<br />

Roger Scruton<br />

New York: Beaufort Books, 2014<br />

father had been put in prison in the 1970s and he had<br />

died there, too. His only crime had been running an<br />

informal reading club, discussing authors like Kafka,<br />

Dostoyevsky, and Camus with a few close friends.<br />

After his father’s death, Jan stays with his<br />

mother in Prague, works as a cleaner, and spends most<br />

of his time “underground”—riding the city’s metro<br />

lines. There he likes to read books belonging to his<br />

father: Czech classics and authors from the period<br />

of late Austro-Hungarian Empire, people like Franz<br />

Kafka, Joseph Roth, and Stephan Zweig. He also<br />

reads Dostoyevsky, whose Notes from the Underground<br />

he carries around with him all the time. Inspired by<br />

his literary heroes, Jan soon decides to pen several<br />

short stories under the title Rumors and signs them as<br />

“Comrade Androš”, the name derived from the Czech<br />

term for “underground”—that is, a comrade from<br />

under the ground.<br />

His mother, who types copies of dissident<br />

literature on a typewriter for others, then makes several<br />

copies of Jan’s Rumors—until she eventually gets<br />

The European Conservative 37