CONSERVATIVE

eurocon_12_2015_summer-fall

eurocon_12_2015_summer-fall

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

“the body in its entirety would become … an instrument<br />

of pleasure”. The sexual liberation Marcuse hailed<br />

was not a fecund liberation. As in Brave New World,<br />

children do not enter into the equation. The issue is<br />

pleasure, not progeny. Marcuse speaks glowingly of “a<br />

resurgence of pregenital polymorphous sexuality” that<br />

“protests against the repressive order of procreative<br />

sexuality”. A look at the alarmingly low birth rates of<br />

most affluent nations today suggests that the protest<br />

has been effective.<br />

When Tocqueville warned about the peculiar<br />

form of despotism that threatened democracy, he noted<br />

that instead of tyrannizing men, as past despotisms had<br />

done, it tended to infantilize them, keeping “them fixed<br />

irrevocably in childhood”. What Tocqueville warned<br />

about, Marcuse celebrated, extolling the benefits<br />

of returning to a state of what he called “primary<br />

narcissism”. What Marcuse encouraged, in other<br />

words, is solipsism, not as a philosophical principle but<br />

as a moral indulgence, a way of life. I note in passing<br />

that Marcuse was a college professor: How proud he<br />

would be of those contemporary universities which<br />

have, partly under his influence, become factories for<br />

the maintenance of infantilizing narcissism.<br />

A couple of concluding observations: In Notes<br />

towards a Definition of Culture, T. S. Eliot observed that<br />

“culture is the one thing that we cannot deliberately<br />

aim at. It is the product of a variety of more or less<br />

harmonious activities, each pursued for its own sake”.<br />

“For its own sake”. That is one simple idea that is<br />

everywhere imperilled today. When we plant a garden,<br />

it is bootless to strive directly for camellias. They are<br />

the natural product of our care, nurture, and time. We<br />

can manage that when it comes to agriculture. When<br />

we turn our hands to cultura animi, we seem to be<br />

considerably less successful.<br />

Let me end by noting that the opposite of<br />

“conservative” is not “liberal” but ephemeral. Russell<br />

Kirk once observed that he was conservative because<br />

he was liberal, that is, committed to freedom. Kirk’s<br />

formulation may sound paradoxical, but it touches on a<br />

great truth. To be conservative: that means wanting to<br />

conserve what is worth preserving from the ravages of<br />

time and ideology, evil and stupidity, so that freedom<br />

may thrive. In some plump eras the task is so easy we<br />

can almost forget how necessary it is. At other times, the<br />

enemies of civilization transform the task of preserving<br />

of culture into a battle for survival. That, I believe—<br />

and I say regretfully—is where we are today.<br />

Roger Kimball is Editor and Publisher of The New Criterion<br />

and President and Publisher of Encounter Books. He is an art<br />

critic for National Review and writes a regular column for PJ<br />

Media. This article was originally delivered as a lecture at the<br />

annual meeting of the Philadelphia Society on March 28, 2015.<br />

It appears here with permission.<br />

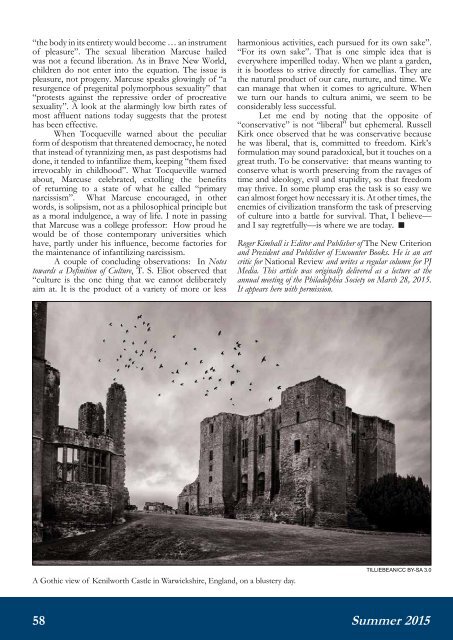

A Gothic view of Kenilworth Castle in Warwickshire, England, on a blustery day.<br />

TILLIEBEAN/CC BY-SA 3.0<br />

58<br />

Summer 2015