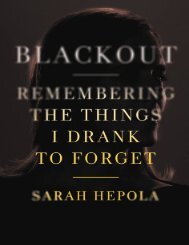

Blackout_ Remembering the Things I Drank to Forget - Sarah Hepola

I’m in Paris on a magazine assignment, which is exactly as great as it sounds. I eat dinner at a restaurant so fancy I have to keep resisting the urge to drop my fork just to see how fast someone will pick it up. I’m drinking cognac—the booze of kings and rap stars—and I love how the snifter sinks between the crooks of my fingers, amber liquid sloshing up the sides as I move it in a figure eight. Like swirling the ocean in the palm of my hand.

I’m in Paris on a magazine assignment, which is exactly as great as it sounds. I eat dinner at a

restaurant so fancy I have to keep resisting the urge to drop my fork just to see how fast someone will

pick it up. I’m drinking cognac—the booze of kings and rap stars—and I love how the snifter sinks

between the crooks of my fingers, amber liquid sloshing up the sides as I move it in a figure eight.

Like swirling the ocean in the palm of my hand.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

newspaper reporter growing up among <strong>the</strong> free-clinking bottles of postwar America, Hamill built his<br />

identity on booze. But ultimately he quit, because it was bad for business.<br />

It was bad for mine, <strong>to</strong>o. So much was lost on me when I was drinking. What we did last night,<br />

what was said. I s<strong>to</strong>pped being an observer and became way <strong>to</strong>o much of a participant. I still<br />

introduce myself <strong>to</strong> people, only <strong>to</strong> receive <strong>the</strong> brittle rejoinder of “We’ve met, like, four times.”<br />

Memory erodes as we age. Did I really need <strong>to</strong> be accelerating my decline?<br />

I’m not saying great writers don’t drink, because <strong>the</strong>y certainly do, and some part of me will<br />

probably always wish I stayed one of <strong>the</strong>m.<br />

I sometimes read s<strong>to</strong>ries by women who are using, and <strong>the</strong>y speak in a seductive purr. They have<br />

<strong>the</strong> in<strong>to</strong>xicating rhythm of a person writing without inhibitions. Those pieces can trigger a <strong>to</strong>xic envy<br />

in me. Maybe I should do drugs, I think. Maybe I should drink again. How come she gets <strong>to</strong> do that—<br />

and I can’t?<br />

Mine are childish urges, <strong>the</strong> gimme-gimme for ano<strong>the</strong>r kid’s <strong>to</strong>ys. The real problem is that I still<br />

fear my own talent is deficient. This isn’t merely a problem for writers who drink; it’s a problem for<br />

drinkers and writers, period. We are cursed by a gnawing fear that whatever we are—it’s not good<br />

enough.<br />

If I stew in that <strong>to</strong>xic envy <strong>to</strong>o long, I start <strong>to</strong> teeter. Those are <strong>the</strong> days when my eyes can get<br />

pulled by a glass of champagne, throwing its confetti in<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> air, or <strong>the</strong> klop-klop of a martini being<br />

shaken in a metal cup. What a powerful voodoo—<strong>to</strong> believe brilliance could be sipped or poured.<br />

I read an interview with Toni Morrison once. She came in<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> literary world during <strong>the</strong> drugaddled<br />

New Journalism era, but she never bought <strong>the</strong> hype. “I want <strong>to</strong> feel what I feel,” she said.<br />

“Even if it’s not happiness.”<br />

That is true strength. To want what you have, and not what someone else is holding.<br />

ABOUT THREE YEARS after getting sober, I decided <strong>to</strong> learn guitar, something I’d been saying I would<br />

do for years. My author’s bio used <strong>to</strong> read “<strong>Sarah</strong> <strong>Hepola</strong> would like <strong>to</strong> learn how <strong>to</strong> play guitar,” as<br />

if this ability came from Mount Olympus. I bought an acoustic from my friend Mary, and I holed up in<br />

my bedroom, and <strong>the</strong>n I figured out why I never did this in all <strong>the</strong> years of floating on <strong>the</strong> booze barge.<br />

It was incredibly difficult.<br />

Strumming looked easy, but it was awkward and physically unpleasant at first. It <strong>to</strong>ok hours <strong>to</strong><br />

even form <strong>the</strong> finger strength <strong>to</strong> make a handful of chords.<br />

“I think something’s wrong with my hands,” I <strong>to</strong>ld my teacher, one of <strong>the</strong> best guitarists in <strong>to</strong>wn.<br />

He assured me that no, my hands were fine. Learning guitar was really that hard.<br />

“You don’t think my hands are <strong>to</strong>o small?” I asked.<br />

“I teach eight-year-old girls <strong>to</strong> play guitar,” he said. “You’re fine.”<br />

But I bet eight-year-old girls don’t wri<strong>the</strong> with <strong>the</strong> humiliation of being a middle-age beginner. I<br />

was confronting <strong>the</strong> same poisonous self-consciousness and perfectionism that had kept me from<br />

speaking Spanish when I was in Ecuador, that kept me from dancing in public when I was sober, that<br />

kept me locked up all my life. I hated feeling stupid.<br />

“Your problem is that you step up <strong>to</strong> every plate and expect <strong>to</strong> hit a grand slam,” a friend <strong>to</strong>ld me,<br />

and I said, “Yes, exactly!” as though I were simply grateful for <strong>the</strong> diagnosis. Drinking had fueled<br />

such impatience and grandiosity in me.