DESIGNING PROJECTS IN A RAPIDLY CHANGING WORLD

srun3013fp1

srun3013fp1

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

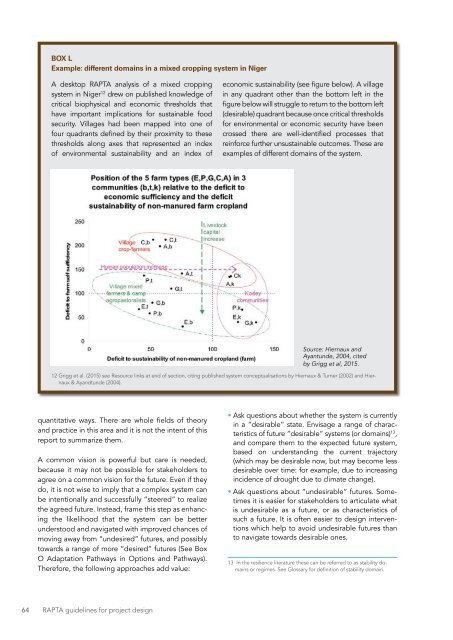

BOX L<br />

Example: different domains in a mixed cropping system in Niger<br />

A desktop RAPTA analysis of a mixed cropping<br />

system in Niger 12 drew on published knowledge of<br />

critical biophysical and economic thresholds that<br />

have important implications for sustainable food<br />

security. Villages had been mapped into one of<br />

four quadrants defined by their proximity to these<br />

thresholds along axes that represented an index<br />

of environmental sustainability and an index of<br />

economic sustainability (see figure below). A village<br />

in any quadrant other than the bottom left in the<br />

figure below will struggle to return to the bottom left<br />

(desirable) quadrant because once critical thresholds<br />

for environmental or economic security have been<br />

crossed there are well-identified processes that<br />

reinforce further unsustainable outcomes. These are<br />

examples of different domains of the system.<br />

Source: Hiernaux and<br />

Ayantunde, 2004, cited<br />

by Grigg et al, 2015.<br />

12 Grigg et al. (2015) see Resource links at end of section, citing published system conceptualisations by Hiernaux & Turner (2002) and Hiernaux<br />

& Ayandtunde (2004).<br />

quantitative ways. There are whole fields of theory<br />

and practice in this area and it is not the intent of this<br />

report to summarize them.<br />

A common vision is powerful but care is needed,<br />

because it may not be possible for stakeholders to<br />

agree on a common vision for the future. Even if they<br />

do, it is not wise to imply that a complex system can<br />

be intentionally and successfully “steered” to realize<br />

the agreed future. Instead, frame this step as enhancing<br />

the likelihood that the system can be better<br />

understood and navigated with improved chances of<br />

moving away from “undesired” futures, and possibly<br />

towards a range of more “desired” futures (See Box<br />

O Adaptation Pathways in Options and Pathways).<br />

Therefore, the following approaches add value:<br />

• Ask questions about whether the system is currently<br />

in a “desirable” state. Envisage a range of characteristics<br />

of future “desirable” systems (or domains) 13 ,<br />

and compare them to the expected future system,<br />

based on understanding the current trajectory<br />

(which may be desirable now, but may become less<br />

desirable over time: for example, due to increasing<br />

incidence of drought due to climate change).<br />

• Ask questions about “undesirable” futures. Sometimes<br />

it is easier for stakeholders to articulate what<br />

is undesirable as a future, or as characteristics of<br />

such a future. It is often easier to design interventions<br />

which help to avoid undesirable futures than<br />

to navigate towards desirable ones.<br />

13 In the resilience literature these can be referred to as stability domains<br />

or regimes. See Glossary for definition of stability domain.<br />

64 RAPTA guidelines for project design