Illiquid assets

Unwrapping alternative returns Global Investor, 01/2015 Credit Suisse

Unwrapping alternative returns

Global Investor, 01/2015

Credit Suisse

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

GLOBAL INVESTOR 1.15 — 17<br />

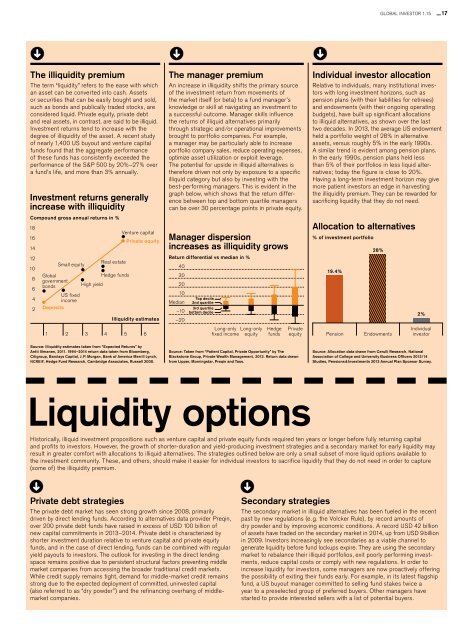

The illiquidity premium<br />

The term “liquidity” refers to the ease with which<br />

an asset can be converted into cash. Assets<br />

or securities that can be easily bought and sold,<br />

such as bonds and publically traded stocks, are<br />

considered liquid. Private equity, private debt<br />

and real <strong>assets</strong>, in contrast, are said to be illiquid.<br />

Investment returns tend to increase with the<br />

degree of illiquidity of the asset. A recent study<br />

of nearly 1,400 US buyout and venture capital<br />

funds found that the aggregate performance<br />

of these funds has consistently exceeded the<br />

performance of the S&P 500 by 20%–27% over<br />

a fund’s life, and more than 3% annually.<br />

Investment returns generally<br />

increase with illiquidity<br />

Compound gross annual returns in %<br />

18<br />

16<br />

14<br />

12<br />

10<br />

8<br />

6<br />

4<br />

2<br />

Global<br />

government<br />

bonds<br />

Small equity<br />

US fixed<br />

income<br />

Deposits<br />

High yield<br />

Real estate<br />

Hedge funds<br />

1 2 3 4 5<br />

Venture capital<br />

Private equity<br />

<strong>Illiquid</strong>ity estimates<br />

6<br />

The manager premium<br />

An increase in illiquidity shifts the primary source<br />

of the investment return from movements of<br />

the market itself (or beta) to a fund manager’s<br />

knowledge or skill at navigating an investment to<br />

a successful outcome. Manager skills influence<br />

the returns of illiquid alternatives primarily<br />

through strategic and/or operational improvements<br />

brought to portfolio companies. For example,<br />

a manager may be particularly able to increase<br />

portfolio company sales, reduce operating expenses,<br />

optimize asset utilization or exploit leverage.<br />

The potential for upside in illiquid alternatives is<br />

therefore driven not only by exposure to a specific<br />

illiquid category but also by investing with the<br />

best-performing managers. This is evident in the<br />

graph below, which shows that the return difference<br />

between top and bottom quartile managers<br />

can be over 30 percentage points in private equity.<br />

Manager dispersion<br />

increases as illiquidity grows<br />

Return differential vs median in %<br />

40<br />

30<br />

20<br />

10<br />

Top decile<br />

Median 2nd quartile<br />

3rd quartile<br />

–10 bottom decile<br />

–20<br />

Long-only Long-only<br />

fixed income equity<br />

Hedge<br />

funds<br />

Private<br />

equity<br />

Individual investor allocation<br />

Relative to individuals, many institutional investors<br />

with long investment horizons, such as<br />

pension plans (with their liabilities for retirees)<br />

and endowments (with their ongoing operating<br />

budgets), have built up significant allocations<br />

to illiquid alternatives, as shown over the last<br />

two decades. In 2013, the average US endowment<br />

held a portfolio weight of 28% in alternative<br />

<strong>assets</strong>, versus roughly 5% in the early 1990s.<br />

A similar trend is evident among pension plans.<br />

In the early 1990s, pension plans held less<br />

than 5% of their portfolios in less liquid alternatives;<br />

today the figure is close to 20%.<br />

Having a long-term investment horizon may give<br />

more patient investors an edge in harvesting<br />

the illiquidity premium. They can be rewarded for<br />

sacrificing liquidity that they do not need.<br />

Allocation to alternatives<br />

% of investment portfolio<br />

19.4%<br />

Pension<br />

28%<br />

Endowments<br />

2%<br />

Individual<br />

investor<br />

Source: <strong>Illiquid</strong>ity estimates taken from “Expected Returns” by<br />

Antti Illmanen, 2011. 1994–2014 return data taken from Bloomberg,<br />

Citigroup, Barclays Capital, J. P. Morgan, Bank of America Merrill Lynch,<br />

NCREIF, Hedge Fund Research, Cambridge Associates, Russell 2000.<br />

Source: Taken from “Patient Capital, Private Opportunity” by The<br />

Blackstone Group, Private Wealth Management, 2013. Return data drawn<br />

from Lipper, Morningstar, Preqin and Tass.<br />

Source: Allocation data drawn from Cerulli Research, National<br />

Association of College and University Business Officers 2013/14<br />

Studies, Pensions & Investments 2013 Annual Plan Sponsor Survey.<br />

Liquidity options<br />

Historically, illiquid investment propositions such as venture capital and private equity funds required ten years or longer before fully returning capital<br />

and profits to investors. However, the growth of shorter-duration and yield-producing investment strategies and a secondary market for early liquidity may<br />

result in greater comfort with allocations to illiquid alternatives. The strategies outlined below are only a small subset of more liquid options available to<br />

the investment community. These, and others, should make it easier for individual investors to sacrifice liquidity that they do not need in order to capture<br />

(some of) the illiquidity premium.<br />

Private debt strategies<br />

The private debt market has seen strong growth since 2008, primarily<br />

driven by direct lending funds. According to alternatives data provider Preqin,<br />

over 200 private debt funds have raised in excess of USD 100 billion of<br />

new capital commitments in 2013–2014. Private debt is characterized by<br />

shorter investment duration relative to venture capital and private equity<br />

funds, and in the case of direct lending, funds can be combined with regular<br />

yield payouts to investors. The outlook for investing in the direct lending<br />

space remains positive due to persistent structural factors preventing middle<br />

market companies from accessing the broader traditional credit markets.<br />

While credit supply remains tight, demand for middle-market credit remains<br />

strong due to the expected deployment of committed, uninvested capital<br />

(also referred to as “dry powder”) and the refinancing overhang of middlemarket<br />

companies.<br />

Secondary strategies<br />

The secondary market in illiquid alternatives has been fueled in the recent<br />

past by new regulations (e. g. the Volcker Rule), by record amounts of<br />

dry powder and by improving economic conditions. A record USD 42 billion<br />

of <strong>assets</strong> have traded on the secondary market in 2014, up from USD 9 billion<br />

in 2009. Investors increasingly see secondaries as a viable channel to<br />

generate liquidity before fund lockups expire. They are using the secondary<br />

market to rebalance their illiquid portfolios, exit poorly performing investments,<br />

reduce capital costs or comply with new regulations. In order to<br />

increase liquidity for investors, some managers are now proactively offering<br />

the possibility of exiting their funds early. For example, in its latest flagship<br />

fund, a US buyout manager committed to selling fund stakes twice a<br />

year to a preselected group of preferred buyers. Other managers have<br />

started to provide interested sellers with a list of potential buyers.