Climate Action 2014-2015

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

RESILIENT CITIES<br />

"Developers will still need<br />

to convert a significant<br />

amount of land from rural to<br />

urban uses to accommodate<br />

burgeoning urban<br />

populations."<br />

published Fifth Assessment Report of the<br />

Intergovernmental Panel on <strong>Climate</strong><br />

Change (IPCC) estimate that, between<br />

2000 and 2030, the urban footprint will<br />

increase between 56 and 310 per cent.<br />

They reckon that “55 per cent of the<br />

total urban land in 2030 is expected to<br />

be built in the first three decades of the<br />

21st century”. Given that some significant<br />

amount of rural-to-urban land conversion<br />

will occur in coming decades, it behoves<br />

us to develop that land in as sustainable a<br />

manner as possible.<br />

Given these circumstances, how can<br />

a planned approach to city extensions<br />

provide for more climate-friendly urban<br />

development? By designing urban areas<br />

well from the very beginning we begin<br />

to accrue substantial climate benefits and<br />

co-benefits now – and avoid locking<br />

in unsustainable development patterns<br />

that may require costly retrofits and<br />

redevelopment schemes in the future.<br />

On the mitigation side, well-planned<br />

city extensions can reduce greenhouse<br />

gas emissions by providing for more<br />

compact urban development , with<br />

well-integrated public transport options<br />

and a mix of land use types. Today,<br />

such conditions are found more often<br />

in urban centres than in low-density,<br />

single-use-zoned suburbs. The problem<br />

is that this latter pattern of suburban<br />

development, which has prevailed in<br />

North America and elsewhere since<br />

World War II, results in higher emissions<br />

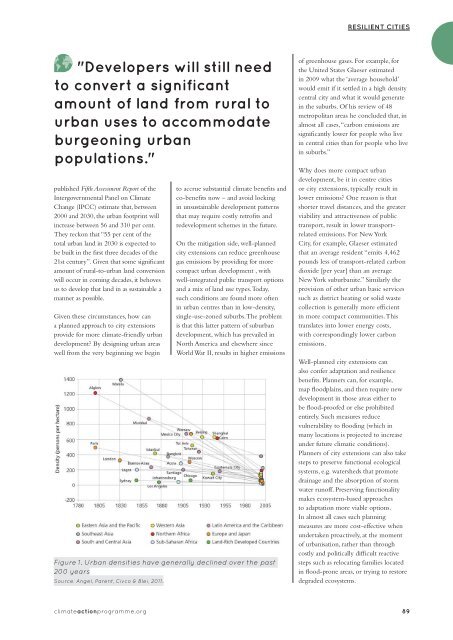

Figure 1. Urban densities have generally declined over the past<br />

200 years<br />

Source: Angel, Parent, Civco & Blei, 2011.<br />

of greenhouse gases. For example, for<br />

the United States Glaeser estimated<br />

in 2009 what the ‘average household’<br />

would emit if it settled in a high density<br />

central city and what it would generate<br />

in the suburbs. Of his review of 48<br />

metropolitan areas he concluded that, in<br />

almost all cases, “carbon emissions are<br />

significantly lower for people who live<br />

in central cities than for people who live<br />

in suburbs.”<br />

Why does more compact urban<br />

development, be it in centre cities<br />

or city extensions, typically result in<br />

lower emissions? One reason is that<br />

shorter travel distances, and the greater<br />

viability and attractiveness of public<br />

transport, result in lower transportrelated<br />

emissions. For New York<br />

City, for example, Glaeser estimated<br />

that an average resident “emits 4,462<br />

pounds less of transport-related carbon<br />

dioxide [per year] than an average<br />

New York suburbanite.” Similarly the<br />

provision of other urban basic services<br />

such as district heating or solid waste<br />

collection is generally more efficient<br />

in more compact communities. This<br />

translates into lower energy costs,<br />

with correspondingly lower carbon<br />

emissions.<br />

Well-planned city extensions can<br />

also confer adaptation and resilience<br />

benefits. Planners can, for example,<br />

map floodplains, and then require new<br />

development in those areas either to<br />

be flood-proofed or else prohibited<br />

entirely. Such measures reduce<br />

vulnerability to flooding (which in<br />

many locations is projected to increase<br />

under future climatic conditions).<br />

Planners of city extensions can also take<br />

steps to preserve functional ecological<br />

systems, e.g. watersheds that promote<br />

drainage and the absorption of storm<br />

water runoff. Preserving functionality<br />

makes ecosystem-based approaches<br />

to adaptation more viable options.<br />

In almost all cases such planning<br />

measures are more cost-effective when<br />

undertaken proactively, at the moment<br />

of urbanisation, rather than through<br />

costly and politically difficult reactive<br />

steps such as relocating families located<br />

in flood-prone areas, or trying to restore<br />

degraded ecosystems.<br />

climateactionprogramme.org 89