part 1 - Iccrom

part 1 - Iccrom

part 1 - Iccrom

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

MEASURING HERITAGE CONSERVATION PERFORMANCE<br />

6th International Seminar on Urban Conservation<br />

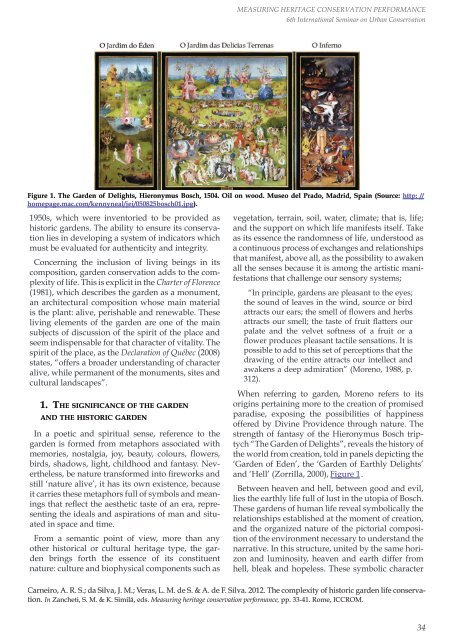

Figure 1. The Garden of Delights, Hieronymus Bosch, 1504. Oil on wood. Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain (Source: http: //<br />

homepage.mac.com/kennyneal/jei/050825bosch01.jpg).<br />

1950s, which were inventoried to be provided as<br />

historic gardens. The ability to ensure its conservation<br />

lies in developing a system of indicators which<br />

must be evaluated for authenticity and integrity.<br />

Concerning the inclusion of living beings in its<br />

composition, garden conservation adds to the complexity<br />

of life. This is explicit in the Charter of Florence<br />

(1981), which describes the garden as a monument,<br />

an architectural composition whose main material<br />

is the plant: alive, perishable and renewable. These<br />

living elements of the garden are one of the main<br />

subjects of discussion of the spirit of the place and<br />

seem indispensable for that character of vitality. The<br />

spirit of the place, as the Declaration of Québec (2008)<br />

states, “offers a broader understanding of character<br />

alive, while permanent of the monuments, sites and<br />

cultural landscapes”.<br />

1. The significance of the garden<br />

and the historic garden<br />

In a poetic and spiritual sense, reference to the<br />

garden is formed from metaphors associated with<br />

memories, nostalgia, joy, beauty, colours, flowers,<br />

birds, shadows, light, childhood and fantasy. Nevertheless,<br />

be nature transformed into fireworks and<br />

still ‘nature alive’, it has its own existence, because<br />

it carries these metaphors full of symbols and meanings<br />

that reflect the aesthetic taste of an era, representing<br />

the ideals and aspirations of man and situated<br />

in space and time.<br />

From a semantic point of view, more than any<br />

other historical or cultural heritage type, the garden<br />

brings forth the essence of its constituent<br />

nature: culture and biophysical components such as<br />

vegetation, terrain, soil, water, climate; that is, life;<br />

and the support on which life manifests itself. Take<br />

as its essence the randomness of life, understood as<br />

a continuous process of exchanges and relationships<br />

that manifest, above all, as the possibility to awaken<br />

all the senses because it is among the artistic manifestations<br />

that challenge our sensory systems;<br />

“In principle, gardens are pleasant to the eyes;<br />

the sound of leaves in the wind, source or bird<br />

attracts our ears; the smell of flowers and herbs<br />

attracts our smell; the taste of fruit flatters our<br />

palate and the velvet softness of a fruit or a<br />

flower produces pleasant tactile sensations. It is<br />

possible to add to this set of perceptions that the<br />

drawing of the entire attracts our intellect and<br />

awakens a deep admiration” (Moreno, 1988, p.<br />

312).<br />

When referring to garden, Moreno refers to its<br />

origins pertaining more to the creation of promised<br />

paradise, exposing the possibilities of happiness<br />

offered by Divine Providence through nature. The<br />

strength of fantasy of the Hieronymus Bosch triptych<br />

“The Garden of Delights”, reveals the history of<br />

the world from creation, told in panels depicting the<br />

‘Garden of Eden’, the ‘Garden of Earthly Delights’<br />

and ‘Hell’ (Zorrilla, 2000), Figure 1.<br />

Between heaven and hell, between good and evil,<br />

lies the earthly life full of lust in the utopia of Bosch.<br />

These gardens of human life reveal symbolically the<br />

relationships established at the moment of creation,<br />

and the organized nature of the pictorial composition<br />

of the environment necessary to understand the<br />

narrative. In this structure, united by the same horizon<br />

and luminosity, heaven and earth differ from<br />

hell, bleak and hopeless. These symbolic character<br />

Carneiro, A. R. S.; da Silva, J. M.; Veras, L. M. de S. & A. de F. Silva. 2012. The complexity of historic garden life conservation.<br />

In Zancheti, S. M. & K. Similä, eds. Measuring heritage conservation performance, pp. 33-41. Rome, ICCROM.<br />

34