CDE Appendix 1 Literature Review - Central East Local Health ...

CDE Appendix 1 Literature Review - Central East Local Health ...

CDE Appendix 1 Literature Review - Central East Local Health ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

The Culture, Diversity and Equity Project: <strong>Literature</strong> <strong>Review</strong><br />

3.1), and take Canadian policy-makers to task for failing to sufficiently elaborate clearer ethical foundations for<br />

health equity policies. 16<br />

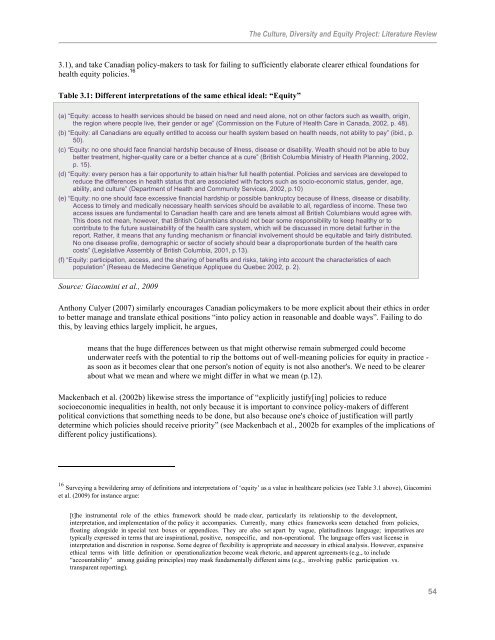

Table 3.1: Different interpretations of the same ethical ideal: “Equity”<br />

(a) “Equity: access to health services should be based on need and need alone, not on other factors such as wealth, origin,<br />

the region where people live, their gender or age” (Commission on the Future of <strong>Health</strong> Care in Canada, 2002, p. 48).<br />

(b) “Equity: all Canadians are equally entitled to access our health system based on health needs, not ability to pay” (ibid., p.<br />

50).<br />

(c) “Equity: no one should face financial hardship because of illness, disease or disability. Wealth should not be able to buy<br />

better treatment, higher-quality care or a better chance at a cure” (British Columbia Ministry of <strong>Health</strong> Planning, 2002,<br />

p. 15).<br />

(d) “Equity: every person has a fair opportunity to attain his/her full health potential. Policies and services are developed to<br />

reduce the differences in health status that are associated with factors such as socio-economic status, gender, age,<br />

ability, and culture” (Department of <strong>Health</strong> and Community Services, 2002, p.10)<br />

(e) “Equity: no one should face excessive financial hardship or possible bankruptcy because of illness, disease or disability.<br />

Access to timely and medically necessary health services should be available to all, regardless of income. These two<br />

access issues are fundamental to Canadian health care and are tenets almost all British Columbians would agree with.<br />

This does not mean, however, that British Columbians should not bear some responsibility to keep healthy or to<br />

contribute to the future sustainability of the health care system, which will be discussed in more detail further in the<br />

report. Rather, it means that any funding mechanism or financial involvement should be equitable and fairly distributed.<br />

No one disease profile, demographic or sector of society should bear a disproportionate burden of the health care<br />

costs” (Legislative Assembly of British Columbia, 2001, p.13).<br />

(f) “Equity: participation, access, and the sharing of benefits and risks, taking into account the characteristics of each<br />

population” (Reseau de Medecine Genetique Appliquee du Quebec 2002, p. 2).<br />

Source: Giacomini et al., 2009<br />

Anthony Culyer (2007) similarly encourages Canadian policymakers to be more explicit about their ethics in order<br />

to better manage and translate ethical positions “into policy action in reasonable and doable ways”. Failing to do<br />

this, by leaving ethics largely implicit, he argues,<br />

means that the huge differences between us that might otherwise remain submerged could become<br />

underwater reefs with the potential to rip the bottoms out of well-meaning policies for equity in practice -<br />

as soon as it becomes clear that one person's notion of equity is not also another's. We need to be clearer<br />

about what we mean and where we might differ in what we mean (p.12).<br />

Mackenbach et al. (2002b) likewise stress the importance of “explicitly justify[ing] policies to reduce<br />

socioeconomic inequalities in health, not only because it is important to convince policy-makers of different<br />

political convictions that something needs to be done, but also because one's choice of justification will partly<br />

determine which policies should receive priority” (see Mackenbach et al., 2002b for examples of the implications of<br />

different policy justifications).<br />

16 Surveying a bewildering array of definitions and interpretations of ‘equity’ as a value in healthcare policies (see Table 3.1 above), Giacomini<br />

et al. (2009) for instance argue:<br />

[t]he instrumental role of the ethics framework should be made clear, particularly its relationship to the development,<br />

interpretation, and implementation of the policy it accompanies. Currently, many ethics frameworks seem detached from policies,<br />

floating alongside in special text boxes or appendices. They are also set apart by vague, platitudinous language; imperatives are<br />

typically expressed in terms that are inspirational, positive, nonspecific, and non-operational. The language offers vast license in<br />

interpretation and discretion in response. Some degree of flexibility is appropriate and necessary in ethical analysis. However, expansive<br />

ethical terms with little definition or operationalization become weak rhetoric, and apparent agreements (e.g., to include<br />

“accountability” among guiding principles) may mask fundamentally different aims (e.g., involving public participation vs.<br />

transparent reporting).<br />

54