Empowering citizens Engaging governments Rebuilding communities

Empowering citizens Engaging governments Rebuilding communities

Empowering citizens Engaging governments Rebuilding communities

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

“[Colonel John Charlton] was the first<br />

person who bought into what CSP was<br />

intended to do. And that has to be stressed,<br />

that the military must buy into it”<br />

—Travis Gartner<br />

2<br />

A complete stabilization package<br />

would set up a smaller area of operations with a joint<br />

security station. The area could be as small as five<br />

city blocks, its total coverage often dictated by the<br />

military presence needed to clear and hold it. “The<br />

military’s idea was that you’d take over an abandoned<br />

house or compound, turn it into your safe house,<br />

secure it, and then start doing missions,” Wilson said.<br />

“But we also had to build relationships with the local<br />

leaders. We prioritized different quick-reaction projects,<br />

stabilization, COIN-type spending. We did a lot of<br />

that in the early days, like the trash cleanup. But you<br />

know, right after fighting, we didn’t have the capacity<br />

to do it on the right level, or with a local face. We filled<br />

the gap until a better option came along. That’s when<br />

CSP came into the mix.”<br />

By November 2006, the Marines had seized a multistory,<br />

dilapidated building at a key vantage point in<br />

Ramadi. Dubbed the 17th Street Security Station, the<br />

building became a critical outpost for US and Iraqi security<br />

forces. With an operational security base established<br />

for the military to hold the surrounding area,<br />

the exact window of opportunity CSP was designed for<br />

opened up. The CSP team and local Iraqi leaders came<br />

together to implement a joint revitalization project to<br />

clean streets, reconstruct buildings, and repair sewage<br />

and electrical lines. The $2.1 million infrastructure<br />

project filled holes in the road and repaved sidewalks. It<br />

created hundreds of local construction jobs. While that<br />

was ongoing, IRD moved quickly to award more than 60<br />

business grants to local entrepreneurs to encourage<br />

investment in the rebuilt market and create longer term<br />

employment. “CSP was looked at by the military as a<br />

great partner,” Wilson said, “because they were willing<br />

to take risks and make things happen. If they had<br />

slowed down and said, ‘Hey we can’t do this because of<br />

X, Y, and Z,’ I don’t think you would’ve seen the drastic<br />

turnaround you saw in Ramadi.”<br />

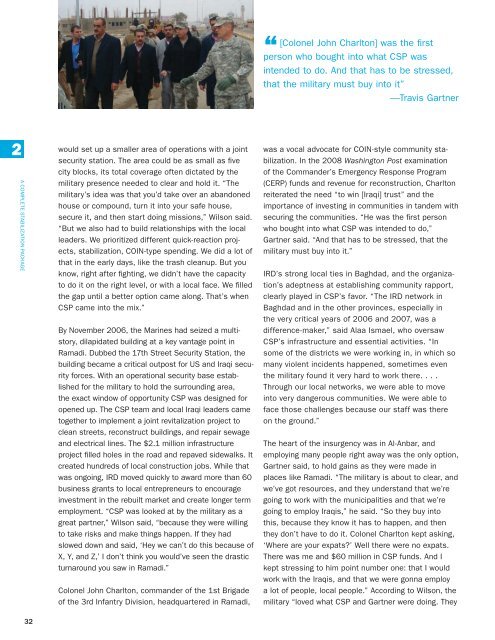

Colonel John Charlton, commander of the 1st Brigade<br />

of the 3rd Infantry Division, headquartered in Ramadi,<br />

was a vocal advocate for COIN-style community stabilization.<br />

In the 2008 Washington Post examination<br />

of the Commander’s Emergency Response Program<br />

(CERP) funds and revenue for reconstruction, Charlton<br />

reiterated the need “to win [Iraqi] trust” and the<br />

importance of investing in <strong>communities</strong> in tandem with<br />

securing the <strong>communities</strong>. “He was the first person<br />

who bought into what CSP was intended to do,”<br />

Gartner said. “And that has to be stressed, that the<br />

military must buy into it.”<br />

IRD’s strong local ties in Baghdad, and the organization’s<br />

adeptness at establishing community rapport,<br />

clearly played in CSP’s favor. “The IRD network in<br />

Baghdad and in the other provinces, especially in<br />

the very critical years of 2006 and 2007, was a<br />

difference-maker,” said Alaa Ismael, who oversaw<br />

CSP’s infrastructure and essential activities. “In<br />

some of the districts we were working in, in which so<br />

many violent incidents happened, sometimes even<br />

the military found it very hard to work there. . . .<br />

Through our local networks, we were able to move<br />

into very dangerous <strong>communities</strong>. We were able to<br />

face those challenges because our staff was there<br />

on the ground.”<br />

The heart of the insurgency was in Al-Anbar, and<br />

employing many people right away was the only option,<br />

Gartner said, to hold gains as they were made in<br />

places like Ramadi. “The military is about to clear, and<br />

we’ve got resources, and they understand that we’re<br />

going to work with the municipalities and that we’re<br />

going to employ Iraqis,” he said. “So they buy into<br />

this, because they know it has to happen, and then<br />

they don’t have to do it. Colonel Charlton kept asking,<br />

‘Where are your expats?’ Well there were no expats.<br />

There was me and $60 million in CSP funds. And I<br />

kept stressing to him point number one: that I would<br />

work with the Iraqis, and that we were gonna employ<br />

a lot of people, local people.” According to Wilson, the<br />

military “loved what CSP and Gartner were doing. They<br />

32

![Guide bonne pratique production d'oignon qualité_VF_4_2411012[1]](https://img.yumpu.com/23506639/1/184x260/guide-bonne-pratique-production-doignon-qualitac-vf-4-24110121.jpg?quality=85)