Empowering citizens Engaging governments Rebuilding communities

Empowering citizens Engaging governments Rebuilding communities

Empowering citizens Engaging governments Rebuilding communities

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

the trash cleanup campaigns were very<br />

high profile, immediately improved life<br />

quality, and, with the rare exception of<br />

a city like Basra, represented CSP’s<br />

initial foray into a community<br />

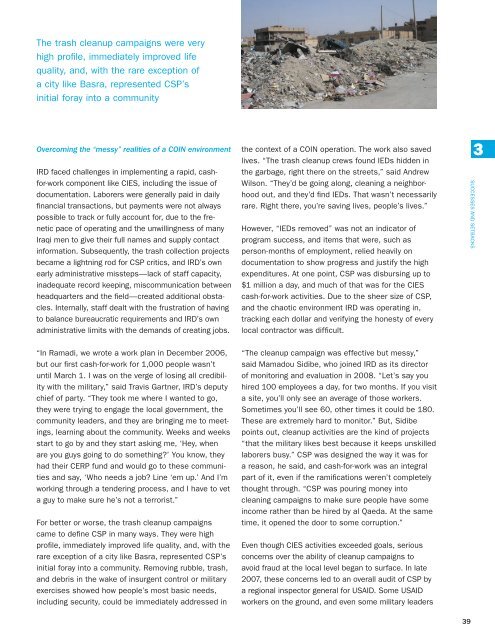

Overcoming the “messy” realities of a COIN environment<br />

IRD faced challenges in implementing a rapid, cashfor-work<br />

component like CIES, including the issue of<br />

documentation. Laborers were generally paid in daily<br />

financial transactions, but payments were not always<br />

possible to track or fully account for, due to the frenetic<br />

pace of operating and the unwillingness of many<br />

Iraqi men to give their full names and supply contact<br />

information. Subsequently, the trash collection projects<br />

became a lightning rod for CSP critics, and IRD’s own<br />

early administrative missteps—lack of staff capacity,<br />

inadequate record keeping, miscommunication between<br />

headquarters and the field—created additional obstacles.<br />

Internally, staff dealt with the frustration of having<br />

to balance bureaucratic requirements and IRD’s own<br />

administrative limits with the demands of creating jobs.<br />

the context of a COIN operation. The work also saved<br />

lives. “The trash cleanup crews found IEDs hidden in<br />

the garbage, right there on the streets,” said Andrew<br />

Wilson. “They’d be going along, cleaning a neighborhood<br />

out, and they’d find IEDs. That wasn’t necessarily<br />

rare. Right there, you’re saving lives, people’s lives.”<br />

However, “IEDs removed” was not an indicator of<br />

program success, and items that were, such as<br />

person-months of employment, relied heavily on<br />

documentation to show progress and justify the high<br />

expenditures. At one point, CSP was disbursing up to<br />

$1 million a day, and much of that was for the CIES<br />

cash-for-work activities. Due to the sheer size of CSP,<br />

and the chaotic environment IRD was operating in,<br />

tracking each dollar and verifying the honesty of every<br />

local contractor was difficult.<br />

3<br />

Successes and setbacks<br />

“In Ramadi, we wrote a work plan in December 2006,<br />

but our first cash-for-work for 1,000 people wasn’t<br />

until March 1. I was on the verge of losing all credibility<br />

with the military,” said Travis Gartner, IRD’s deputy<br />

chief of party. “They took me where I wanted to go,<br />

they were trying to engage the local government, the<br />

community leaders, and they are bringing me to meetings,<br />

learning about the community. Weeks and weeks<br />

start to go by and they start asking me, ‘Hey, when<br />

are you guys going to do something?’ You know, they<br />

had their CERP fund and would go to these <strong>communities</strong><br />

and say, ‘Who needs a job? Line ‘em up.’ And I’m<br />

working through a tendering process, and I have to vet<br />

a guy to make sure he’s not a terrorist.”<br />

For better or worse, the trash cleanup campaigns<br />

came to define CSP in many ways. They were high<br />

profile, immediately improved life quality, and, with the<br />

rare exception of a city like Basra, represented CSP’s<br />

initial foray into a community. Removing rubble, trash,<br />

and debris in the wake of insurgent control or military<br />

exercises showed how people’s most basic needs,<br />

including security, could be immediately addressed in<br />

“The cleanup campaign was effective but messy,”<br />

said Mamadou Sidibe, who joined IRD as its director<br />

of monitoring and evaluation in 2008. “Let’s say you<br />

hired 100 employees a day, for two months. If you visit<br />

a site, you’ll only see an average of those workers.<br />

Sometimes you’ll see 60, other times it could be 180.<br />

These are extremely hard to monitor.” But, Sidibe<br />

points out, cleanup activities are the kind of projects<br />

“that the military likes best because it keeps unskilled<br />

laborers busy.” CSP was designed the way it was for<br />

a reason, he said, and cash-for-work was an integral<br />

part of it, even if the ramifications weren’t completely<br />

thought through. “CSP was pouring money into<br />

cleaning campaigns to make sure people have some<br />

income rather than be hired by al Qaeda. At the same<br />

time, it opened the door to some corruption.”<br />

Even though CIES activities exceeded goals, serious<br />

concerns over the ability of cleanup campaigns to<br />

avoid fraud at the local level began to surface. In late<br />

2007, these concerns led to an overall audit of CSP by<br />

a regional inspector general for USAID. Some USAID<br />

workers on the ground, and even some military leaders<br />

39

![Guide bonne pratique production d'oignon qualité_VF_4_2411012[1]](https://img.yumpu.com/23506639/1/184x260/guide-bonne-pratique-production-doignon-qualitac-vf-4-24110121.jpg?quality=85)