- Page 1:

A 1 E=mc 2 This eBook is downloaded

- Page 4 and 5:

About the Authors Allyson Weseley h

- Page 6 and 7:

Perception Practice Questions 5 Sta

- Page 8:

13 Treatment of Psychological Disor

- Page 11 and 12:

The College Board recently revised

- Page 13:

Overview of the AP Psychology Exam

- Page 16 and 17:

(A) negative reinforcement. (B) sha

- Page 18 and 19:

(B) 2 years (C) 4 years (D) 8 years

- Page 20 and 21:

(A) damage to her fovea. (B) place

- Page 22 and 23:

(A) humanistic. (B) sociocultural.

- Page 24 and 25:

48. In the past when Nuara’s comp

- Page 26 and 27:

(E) central 59. Which part of the b

- Page 28 and 29:

(D) 82 (E) 95 70. The typical age o

- Page 30 and 31:

(C) idiographic (D) sociocultural (

- Page 32 and 33:

(C) long-term memory. (D) echoic me

- Page 34 and 35:

Answer Key DIAGNOSTIC TEST 1. B 36.

- Page 36 and 37:

necessarily related to being creati

- Page 38 and 39:

uses magnetic fields to show both s

- Page 40 and 41:

the high school students taking AP

- Page 42 and 43:

when people’s preexisting beliefs

- Page 44 and 45:

of the trials but simply not had an

- Page 46 and 47:

76. (C) Group therapy tends to be l

- Page 48 and 49:

89. (D) The prefrontal cortex plays

- Page 50 and 51:

MULTIPLE-CHOICE ERROR ANALYSIS SHEE

- Page 52 and 53:

QUESTION 1 SCORING RUBRIC This is a

- Page 54 and 55:

eal-world violence” as the variab

- Page 56 and 57:

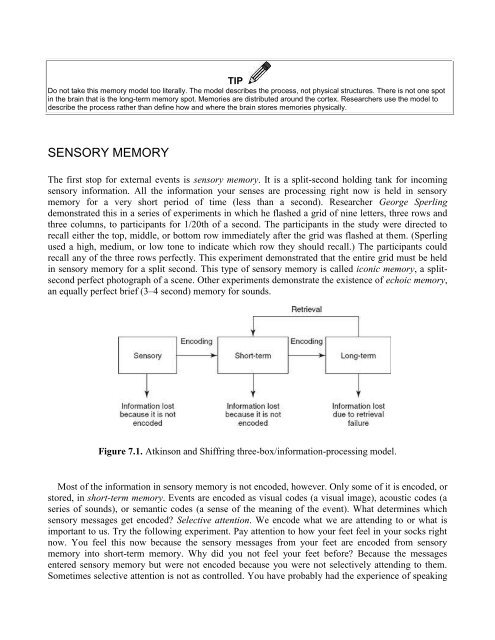

attention determines what informati

- Page 58 and 59:

Also, notice that this (fictional)

- Page 60 and 61:

History and Approaches CHAPTER 1 KE

- Page 62 and 63:

epression—the pushing down into t

- Page 64 and 65:

certain neurotransmitters in the br

- Page 66 and 67:

(D) focused entirely on human males

- Page 68 and 69:

13. Symbolic dream analysis might b

- Page 70 and 71:

10. (D) Watson referred to the cond

- Page 72 and 73:

Coercion Informed consent Anonymity

- Page 74 and 75:

the study and therefore are not par

- Page 76 and 77:

groups may possibly be due not to t

- Page 78 and 79:

irth onward. If I seek to control a

- Page 80 and 81:

since that value is in excess of ev

- Page 82 and 83:

perfect, negative correlation and +

- Page 84 and 85:

In both cases, you would be correct

- Page 86 and 87:

(A) sampling error. (B) the need to

- Page 88 and 89:

II. Having a computer generate a ra

- Page 90 and 91:

accredited commercial sources) and

- Page 92 and 93:

Biological Bases of Behavior CHAPTE

- Page 94 and 95:

Terminal buttons (also called end b

- Page 96 and 97:

Afferent Neurons (or Sensory Neuron

- Page 98 and 99:

heart rate, blood pressure, and res

- Page 100 and 101:

An electroencephalogram (EEG) detec

- Page 102 and 103:

Pons The pons (located just above t

- Page 104 and 105:

sensory messages and controls the m

- Page 106 and 107:

of each retina are processed in the

- Page 108 and 109:

separate families obviously share v

- Page 110 and 111:

(E) neurons, synapses, and cerebral

- Page 112 and 113:

2. (B) The motor cortex (which is l

- Page 114 and 115:

Sensation and Perception CHAPTER 4

- Page 116 and 117:

The first three senses listed here,

- Page 118 and 119:

enough bipolar cells fire, the next

- Page 120 and 121: Figure 4.2. Cross section of the ea

- Page 122 and 123: CHEMICAL SENSES Taste (or Gustation

- Page 124 and 125: BODY POSITION SENSES Vestibular Sen

- Page 126 and 127: Perceptual Theories Psychologists u

- Page 128 and 129: Figure 4.5. Optical illusion. Gesta

- Page 130 and 131: Depth Cues One of the most importan

- Page 132 and 133: 3. In a perception research lab, yo

- Page 134 and 135: 14. What behavior would be difficul

- Page 136 and 137: is being filled in, instead of an i

- Page 138 and 139: OVERVIEW While you are reading this

- Page 140 and 141: Sleep Cycle You may be familiar wit

- Page 142 and 143: up until his graduation from high s

- Page 144 and 145: Researcher Ernest Hilgard explained

- Page 146 and 147: Practice Questions Directions: Each

- Page 148 and 149: 12. In the context of this unit, th

- Page 150 and 151: activation-synthesis theory of drea

- Page 152 and 153: Albert Bandura Edward Tolman Wolfga

- Page 154 and 155: esponse to the white rat. Aversive

- Page 156 and 157: B. F. Skinner, who coined the term

- Page 158 and 159: things in the Skinner box or the ba

- Page 160 and 161: and tend, instead, to bury the disk

- Page 162 and 163: Tolman reasoned that these rats mus

- Page 164 and 165: (B) aversive conditioning. (C) simu

- Page 166 and 167: 1. (B) The music before a scary eve

- Page 168 and 169: important point: the word positive

- Page 172 and 173: with one person at a party but then

- Page 174 and 175: One factor is the order in which th

- Page 176 and 177: memory, is stored elsewhere in the

- Page 178 and 179: THINKING AND CREATIVITY Describing

- Page 180 and 181: very different than what the design

- Page 182 and 183: (D) The words in each language affe

- Page 184 and 185: (C) a child of normal mental abilit

- Page 186 and 187: 14. (C) The critical-period hypothe

- Page 188 and 189: OVERVIEW In my psychology class, I

- Page 190 and 191: motivation to return to the baselin

- Page 192 and 193: hypothalamus act in opposition to c

- Page 194 and 195: Sexual Response Cycle The famous la

- Page 196 and 197: esponds best to can give managers a

- Page 198 and 199: Schachter showed that people who ar

- Page 200 and 201: Practice Questions Directions: Each

- Page 202 and 203: (B) decreased motivation to perform

- Page 204 and 205: equally active in work groups and m

- Page 206 and 207: Konrad Lorenz Harry Harlow Mary Ain

- Page 208 and 209: MOTOR/SENSORY DEVELOPMENT Reflexes

- Page 210 and 211: MARY AINSWORTH Mary Ainsworth resea

- Page 212 and 213: Sigmund Freud Historically, Freud w

- Page 214 and 215: Integrity versus despair Toward the

- Page 216 and 217: Formal operations (12 through adult

- Page 218 and 219: During the next level of moral reas

- Page 220 and 221:

etween the sexes. However, biopsych

- Page 222 and 223:

(A) teratogens. (B) stress on the m

- Page 224 and 225:

(E) authoritative 15. Which of the

- Page 226 and 227:

Personality CHAPTER 10 KEY TERMS Pe

- Page 228 and 229:

Both the Oedipus and Electra crises

- Page 230 and 231:

• Biff continues to act as if he

- Page 232 and 233:

Impact of Freudian Theory Despite i

- Page 234 and 235:

BIOLOGICAL THEORIES Biological theo

- Page 236 and 237:

HUMANISTIC THEORIES Many of the mod

- Page 238 and 239:

psychologists, particularly cogniti

- Page 240 and 241:

(C) identifying core principles by

- Page 242 and 243:

7. (C) Dr. Li is using the TAT (the

- Page 244 and 245:

Testing and Individual Differences

- Page 246 and 247:

same person, it clearly does not ac

- Page 248 and 249:

Charles Spearman One fundamental is

- Page 250 and 251:

created a test that would identify

- Page 252 and 253:

NATURE VERSUS NURTURE: INTELLIGENCE

- Page 254 and 255:

Practice Questions Directions: Each

- Page 256 and 257:

12. Although her score on the perso

- Page 258 and 259:

7. (C) Spearman argued that intelli

- Page 260 and 261:

Abnormal Psychology CHAPTER 12 KEY

- Page 262 and 263:

Disorders (DSM). Periodically, this

- Page 264 and 265:

a situation in which one could emba

- Page 266 and 267:

Dissociative identity disorder (DID

- Page 268 and 269:

A growing body of evidence suggests

- Page 270 and 271:

• Parkinson’s disease, characte

- Page 272 and 273:

Paraphilias or psychosexual disorde

- Page 274 and 275:

Practice Questions Directions: Each

- Page 276 and 277:

(C) cognitive (D) behavioral (E) so

- Page 278 and 279:

psychologists would locate the caus

- Page 280 and 281:

Albert Ellis OVERVIEW Just as there

- Page 282 and 283:

of Consciousness,” is an altered

- Page 284 and 285:

the doctor’s office. His mother m

- Page 286 and 287:

suffering from a social phobia migh

- Page 288 and 289:

The most intrusive and rarest form

- Page 290 and 291:

2. Coretta’s therapist says littl

- Page 292 and 293:

(B) client-centered (C) aversive co

- Page 294 and 295:

9. (B) Transference is when patient

- Page 296 and 297:

Stanley Milgram Irving Janis Philli

- Page 298 and 299:

already said that the boring task w

- Page 300 and 301:

attribution error. Say that you go

- Page 302 and 303:

Origin of Stereotypes and Prejudice

- Page 304 and 305:

that good-looking people are percei

- Page 306 and 307:

TABLE 14.1 Group polarization is th

- Page 308 and 309:

(C) modeling. (D) diffusion of resp

- Page 310 and 311:

14. On the first day of class, Mr.

- Page 312 and 313:

error is a different attributional

- Page 314 and 315:

Here’s another example: A psychol

- Page 316 and 317:

(E) Table manners are learned by re

- Page 318 and 319:

Answering Free-Response Questions C

- Page 320 and 321:

6. When asked about a psychological

- Page 322 and 323:

INTERPRETING THE RUBRIC Notice how

- Page 324 and 325:

Point 4 — Not awarded—The stude

- Page 326 and 327:

(E) PTSD. 5. Which psychological pe

- Page 328 and 329:

(A) social facilitation (B) deindiv

- Page 330 and 331:

(B) contextual intelligence (C) div

- Page 332 and 333:

34. Which of the following statisti

- Page 334 and 335:

(E) adult genital stage. 45. Daniel

- Page 336 and 337:

(D) the fundamental attribution err

- Page 338 and 339:

64. Matt’s research design could

- Page 340 and 341:

(C) the social role hypothesis. (D)

- Page 342 and 343:

(A) social facilitation. (B) confor

- Page 344 and 345:

(D) James-Lange theory (E) opponent

- Page 346 and 347:

Answer Key PRACTICE TEST #1 1. D 36

- Page 348 and 349:

6. (C) Pascale would best be classi

- Page 350 and 351:

18. (B) Counterconditioning lies at

- Page 352 and 353:

29. (E) Of the disorders listed, ma

- Page 354 and 355:

40. (E) Jamie’s printer problems

- Page 356 and 357:

ethics. People with low self-esteem

- Page 358 and 359:

take the energy from impulses they

- Page 360 and 361:

Genna’s right hemisphere was dama

- Page 362 and 363:

SSRIs (serotonin selective reuptake

- Page 364 and 365:

effect would not be particularly he

- Page 366 and 367:

Question 1 Scoring Rubric This is a

- Page 368 and 369:

Part B Point 4 — Yerkes-Dodson la

- Page 370 and 371:

(A) hearing (B) touch (C) balance (

- Page 372 and 373:

(A) proximity and similarity (B) to

- Page 374 and 375:

(C) primary (physical) and secondar

- Page 376 and 377:

(C) unconditional positive regard (

- Page 378 and 379:

(E) Dreams reflect variations in br

- Page 380 and 381:

(C) median (D) mean (E) normal curv

- Page 382 and 383:

(B) semantic memory (C) procedural

- Page 384 and 385:

(D) disorganized, paranoid, cataton

- Page 386 and 387:

(C) Operant conditioning is used to

- Page 388 and 389:

(B) to explain the biomedical sympt

- Page 390 and 391:

Answer Key PRACTICE TEST #2 1. C 36

- Page 392 and 393:

nondamaged parts of the brain and r

- Page 394 and 395:

28. (D) Stimulation of the lateral

- Page 396 and 397:

48. (A) Psychotherapies all involve

- Page 398 and 399:

67. (D) Generalization occurs in cl

- Page 400 and 401:

hybrid cars” and “don’t own h

- Page 402 and 403:

Multiple-Choice Error Analysis Shee

- Page 404 and 405:

Point 3 — Students need to briefl

- Page 406 and 407:

SAMPLE STUDENT RESPONSE ESSAY 2 SCO