Read More - Philippine Institute for Development Studies

Read More - Philippine Institute for Development Studies

Read More - Philippine Institute for Development Studies

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

51<br />

Security against climate variability<br />

through agricultural insurance<br />

Experts agree that agricultural insurance is one of<br />

the best ways to address the adverse impacts of<br />

seasonal climatic variability and secure the welfare<br />

of smallholder farmers. Designed to protect agricultural<br />

producers against loss due to natural calamities, pests, and<br />

other risks, agricultural insurance has a lot of potential<br />

benefits especially in the <strong>Philippine</strong>s where climatic and<br />

other environmental uncertainties are of great concern.<br />

Agricultural insurance in the country is implemented<br />

and managed by the <strong>Philippine</strong> Crop Insurance<br />

Corporation (PCIC). Although the government subsidizes<br />

insurance <strong>for</strong> rice and corn, the PCIC operates as a business<br />

corporation and does not receive any budget from the<br />

government <strong>for</strong> its administrative operations.<br />

Rice and corn insurance constitute about 84 percent<br />

of PCIC’s total business. From 1981 to 2007, the program<br />

was able to serve a total of 3,468,155 farmers, insuring a<br />

total sum of PhP31 billion. Total gross premiums received<br />

during the period exceeded indemnities paid at a ratio<br />

of 1.27:1. Earlier, however, the PCIC had a rough time<br />

during its first decade of operation when damage claims<br />

consistently surpassed premium collections from 1983 to<br />

1989. The program had its highest accomplishment<br />

during the early part of the 1990s when it reached its peak<br />

coverage at 336,000 farmers.<br />

Seasonal climate variability proved to be the top<br />

source of uncertainty <strong>for</strong> rice and corn farmers. Overall,<br />

typhoons and floods were the major causes of production<br />

damage <strong>for</strong> rice while drought was the number one cause<br />

of loss <strong>for</strong> corn. Claims on rice insurance from typhoon<br />

and flooding totaled PhP1.050 billion from 1981 to 2007.<br />

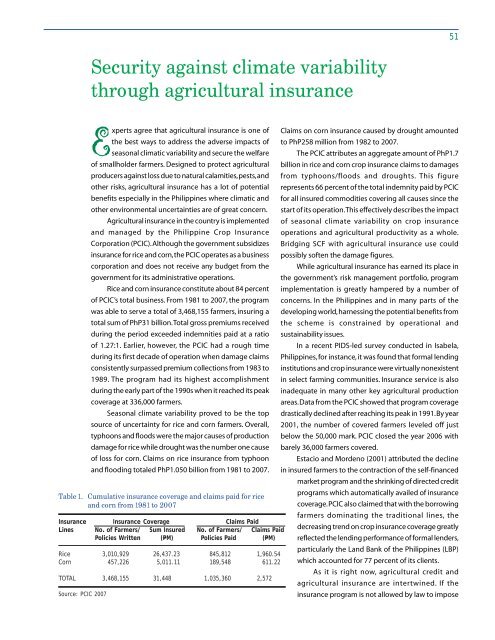

Table 1. Cumulative insurance coverage and claims paid <strong>for</strong> rice<br />

and corn from 1981 to 2007<br />

Insurance Insurance Coverage Claims Paid<br />

Lines No. of Farmers/ Sum Insured No. of Farmers/ Claims Paid<br />

Policies Written (PM) Policies Paid (PM)<br />

Rice 3,010,929 26,437.23 845,812 1,960.54<br />

Corn 457,226 5,011.11 189,548 611.22<br />

TOTAL 3,468,155 31,448 1,035,360 2,572<br />

Source: PCIC 2007<br />

Claims on corn insurance caused by drought amounted<br />

to PhP258 million from 1982 to 2007.<br />

The PCIC attributes an aggregate amount of PhP1.7<br />

billion in rice and corn crop insurance claims to damages<br />

from typhoons/floods and droughts. This figure<br />

represents 66 percent of the total indemnity paid by PCIC<br />

<strong>for</strong> all insured commodities covering all causes since the<br />

start of its operation. This effectively describes the impact<br />

of seasonal climate variability on crop insurance<br />

operations and agricultural productivity as a whole.<br />

Bridging SCF with agricultural insurance use could<br />

possibly soften the damage figures.<br />

While agricultural insurance has earned its place in<br />

the government’s risk management portfolio, program<br />

implementation is greatly hampered by a number of<br />

concerns. In the <strong>Philippine</strong>s and in many parts of the<br />

developing world, harnessing the potential benefits from<br />

the scheme is constrained by operational and<br />

sustainability issues.<br />

In a recent PIDS-led survey conducted in Isabela,<br />

<strong>Philippine</strong>s, <strong>for</strong> instance, it was found that <strong>for</strong>mal lending<br />

institutions and crop insurance were virtually nonexistent<br />

in select farming communities. Insurance service is also<br />

inadequate in many other key agricultural production<br />

areas. Data from the PCIC showed that program coverage<br />

drastically declined after reaching its peak in 1991. By year<br />

2001, the number of covered farmers leveled off just<br />

below the 50,000 mark. PCIC closed the year 2006 with<br />

barely 36,000 farmers covered.<br />

Estacio and Mordeno (2001) attributed the decline<br />

in insured farmers to the contraction of the self-financed<br />

market program and the shrinking of directed credit<br />

programs which automatically availed of insurance<br />

coverage. PCIC also claimed that with the borrowing<br />

farmers dominating the traditional lines, the<br />

decreasing trend on crop insurance coverage greatly<br />

reflected the lending per<strong>for</strong>mance of <strong>for</strong>mal lenders,<br />

particularly the Land Bank of the <strong>Philippine</strong>s (LBP)<br />

which accounted <strong>for</strong> 77 percent of its clients.<br />

As it is right now, agricultural credit and<br />

agricultural insurance are intertwined. If the<br />

insurance program is not allowed by law to impose