Music Theatre since 1990 - Schott Music

Music Theatre since 1990 - Schott Music

Music Theatre since 1990 - Schott Music

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Synopsis<br />

It was surely an act of faith - if not of folly - for me to choose Rinuccini’s old Arianna libretto,<br />

when I could barely make out the meaning of the words. Yet I knew it was right for me, just<br />

as I would have known that Orfeo or Poppea or, for that matter, La Traviata or Lohengrin (had<br />

they been so unfortunate as to lose their music) would not be right. I also knew and this may<br />

seem almost perverse, that it was to be Arianna and not Ariadne - that is Italian and not English.<br />

Common sense led me to experiment with the possibility of an English version, for it would<br />

certainly have made things a lot easier; but in this case I knew that my attraction had as much<br />

to do with the sound as the meaning of the antique Italian [...] My final score is deliberately<br />

patchy: some parts are highly worked, polyphonically and instrumentally; elsewhere the bare<br />

bones of the original are left to stand. The impression I aim to create is one of transparency:<br />

the listener should perceive, both in the successive and simultaneous dimensions of the score,<br />

the old beneath the new and the new arising from the old. We are to see a mythological and<br />

ancient action, interpreted by a 17th-century poet in a modern theatre. My hope, as expressed<br />

by Rinuccini’s Apollo in the (unset) prologue of Arianna, is that ‘it will come to pass that in<br />

these new songs you will admire the ancient glory of the Grecian stage’. (Alexander Goehr,<br />

Royal Opera House programme, 1995)<br />

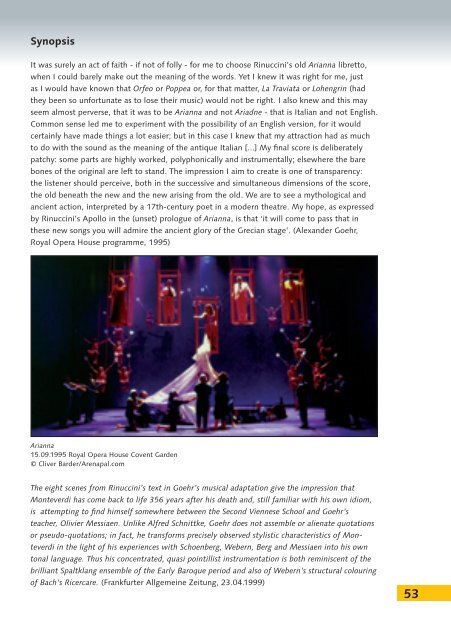

Arianna<br />

15.09.1995 Royal Opera House Covent Garden<br />

© Cliver Barder/Arenapal.com<br />

The eight scenes from Rinuccini’s text in Goehr’s musical adaptation give the impression that<br />

Monteverdi has come back to life 356 years after his death and, still familiar with his own idiom,<br />

is attempting to find himself somewhere between the Second Viennese School and Goehr’s<br />

teacher, Olivier Messiaen. Unlike Alfred Schnittke, Goehr does not assemble or alienate quotations<br />

or pseudo-quotations; in fact, he transforms precisely observed stylistic characteristics of Monteverdi<br />

in the light of his experiences with Schoenberg, Webern, Berg and Messiaen into his own<br />

tonal language. Thus his concentrated, quasi pointillist instrumentation is both reminiscent of the<br />

brilliant Spaltklang ensemble of the Early Baroque period and also of Webern’s structural colouring<br />

of Bach’s Ricercare. (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 23.04.1999)<br />

53