Contents - Konrad Lorenz Institute

Contents - Konrad Lorenz Institute

Contents - Konrad Lorenz Institute

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

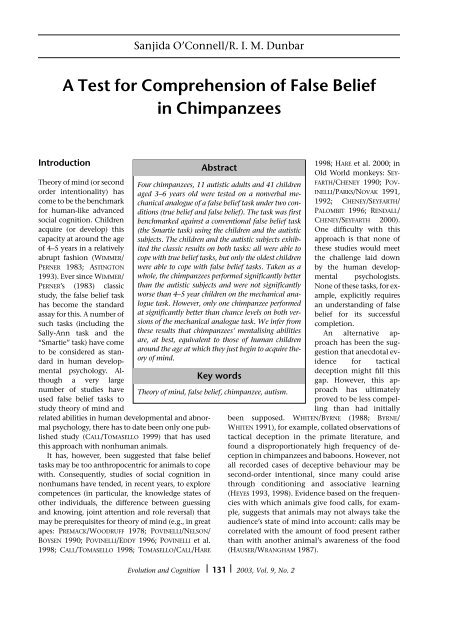

Sanjida O’Connell/R. I. M. Dunbar<br />

A Test for Comprehension of False Belief<br />

in Chimpanzees<br />

Introduction<br />

Theory of mind (or second<br />

order intentionality) has<br />

come to be the benchmark<br />

for human-like advanced<br />

social cognition. Children<br />

acquire (or develop) this<br />

capacity at around the age<br />

of 4–5 years in a relatively<br />

abrupt fashion (WIMMER/<br />

PERNER 1983; ASTINGTON<br />

1993). Ever since WIMMER/<br />

PERNER’s (1983) classic<br />

study, the false belief task<br />

has become the standard<br />

assay for this. A number of<br />

such tasks (including the<br />

Sally-Ann task and the<br />

“Smartie” task) have come<br />

to be considered as standard<br />

in human developmental<br />

psychology. Although<br />

a very large<br />

number of studies have<br />

used false belief tasks to<br />

study theory of mind and<br />

related abilities in human developmental and abnormal<br />

psychology, there has to date been only one published<br />

study (CALL/TOMASELLO 1999) that has used<br />

this approach with nonhuman animals.<br />

It has, however, been suggested that false belief<br />

tasks may be too anthropocentric for animals to cope<br />

with. Consequently, studies of social cognition in<br />

nonhumans have tended, in recent years, to explore<br />

competences (in particular, the knowledge states of<br />

other individuals, the difference between guessing<br />

and knowing, joint attention and role reversal) that<br />

may be prerequisites for theory of mind (e.g., in great<br />

apes: PREMACK/WOODRUFF 1978; POVINELLI/NELSON/<br />

BOYSEN 1990; POVINELLI/EDDY 1996; POVINELLI et al.<br />

1998; CALL/TOMASELLO 1998; TOMASELLO/CALL/HARE<br />

Abstract<br />

Four chimpanzees, 11 autistic adults and 41 children<br />

aged 3–6 years old were tested on a nonverbal mechanical<br />

analogue of a false belief task under two conditions<br />

(true belief and false belief). The task was first<br />

benchmarked against a conventional false belief task<br />

(the Smartie task) using the children and the autistic<br />

subjects. The children and the autistic subjects exhibited<br />

the classic results on both tasks: all were able to<br />

cope with true belief tasks, but only the oldest children<br />

were able to cope with false belief tasks. Taken as a<br />

whole, the chimpanzees performed significantly better<br />

than the autistic subjects and were not significantly<br />

worse than 4–5 year children on the mechanical analogue<br />

task. However, only one chimpanzee performed<br />

at significantly better than chance levels on both versions<br />

of the mechanical analogue task. We infer from<br />

these results that chimpanzees’ mentalising abilities<br />

are, at best, equivalent to those of human children<br />

around the age at which they just begin to acquire theory<br />

of mind.<br />

Key words<br />

Theory of mind, false belief, chimpanzee, autism.<br />

Evolution and Cognition ❘ 131 ❘ 2003, Vol. 9, No. 2<br />

1998; HARE et al. 2000; in<br />

Old World monkeys: SEY-<br />

FARTH/CHENEY 1990; POV-<br />

INELLI/PARKS/NOVAK 1991,<br />

1992; CHENEY/SEYFARTH/<br />

PALOMBIT 1996; RENDALL/<br />

CHENEY/SEYFARTH 2000).<br />

One difficulty with this<br />

approach is that none of<br />

these studies would meet<br />

the challenge laid down<br />

by the human developmental<br />

psychologists.<br />

None of these tasks, for example,<br />

explicitly requires<br />

an understanding of false<br />

belief for its successful<br />

completion.<br />

An alternative approach<br />

has been the suggestion<br />

that anecdotal evidence<br />

for tactical<br />

deception might fill this<br />

gap. However, this approach<br />

has ultimately<br />

proved to be less compelling<br />

than had initially<br />

been supposed. WHITEN/BYRNE (1988; BYRNE/<br />

WHITEN 1991), for example, collated observations of<br />

tactical deception in the primate literature, and<br />

found a disproportionately high frequency of deception<br />

in chimpanzees and baboons. However, not<br />

all recorded cases of deceptive behaviour may be<br />

second-order intentional, since many could arise<br />

through conditioning and associative learning<br />

(HEYES 1993, 1998). Evidence based on the frequencies<br />

with which animals give food calls, for example,<br />

suggests that animals may not always take the<br />

audience’s state of mind into account: calls may be<br />

correlated with the amount of food present rather<br />

than with another animal’s awareness of the food<br />

(HAUSER/WRANGHAM 1987).