Cockroache; Ecology, behavior & history - W.J. Bell

Cockroache; Ecology, behavior & history - W.J. Bell

Cockroache; Ecology, behavior & history - W.J. Bell

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

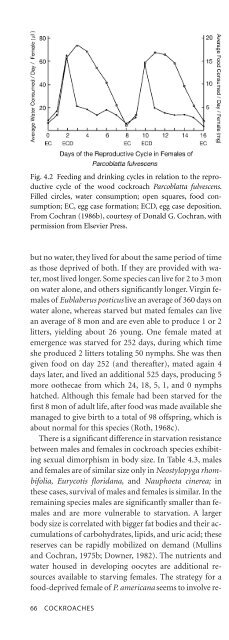

Fig. 4.2 Feeding and drinking cycles in relation to the reproductive<br />

cycle of the wood cockroach Parcoblatta fulvescens.<br />

Filled circles, water consumption; open squares, food consumption;<br />

EC, egg case formation; ECD, egg case deposition.<br />

From Cochran (1986b), courtesy of Donald G. Cochran, with<br />

permission from Elsevier Press.<br />

but no water, they lived for about the same period of time<br />

as those deprived of both. If they are provided with water,<br />

most lived longer. Some species can live for 2 to 3 mon<br />

on water alone, and others significantly longer. Virgin females<br />

of Eublaberus posticus live an average of 360 days on<br />

water alone, whereas starved but mated females can live<br />

an average of 8 mon and are even able to produce 1 or 2<br />

litters, yielding about 26 young. One female mated at<br />

emergence was starved for 252 days, during which time<br />

she produced 2 litters totaling 50 nymphs. She was then<br />

given food on day 252 (and thereafter), mated again 4<br />

days later, and lived an additional 525 days, producing 5<br />

more oothecae from which 24, 18, 5, 1, and 0 nymphs<br />

hatched. Although this female had been starved for the<br />

first 8 mon of adult life, after food was made available she<br />

managed to give birth to a total of 98 offspring, which is<br />

about normal for this species (Roth, 1968c).<br />

There is a significant difference in starvation resistance<br />

between males and females in cockroach species exhibiting<br />

sexual dimorphism in body size. In Table 4.3, males<br />

and females are of similar size only in Neostylopyga rhombifolia,<br />

Eurycotis floridana, and Nauphoeta cinerea; in<br />

these cases, survival of males and females is similar. In the<br />

remaining species males are significantly smaller than females<br />

and are more vulnerable to starvation. A larger<br />

body size is correlated with bigger fat bodies and their accumulations<br />

of carbohydrates, lipids, and uric acid; these<br />

reserves can be rapidly mobilized on demand (Mullins<br />

and Cochran, 1975b; Downer, 1982). The nutrients and<br />

water housed in developing oocytes are additional resources<br />

available to starving females. The strategy for a<br />

food-deprived female of P. americana seems to involve resorption<br />

of yolk-filled eggs, storage of their yolk proteins,<br />

and then rapid incorporation of protein into eggs when<br />

feeding re-ensues (Roth and Stay, 1962b; <strong>Bell</strong>, 1971; <strong>Bell</strong><br />

and Bohm, 1975).<br />

A variety of digestive attributes help cockroaches<br />

buffer food shortages. The large crop allows an individual<br />

to consume a substantial quantity of food at one time.<br />

This bolus then acts as a reservoir during periods of fasting.<br />

When fully distended with food, the crop is a pearshaped<br />

organ about 1.5 cm in length and 0.5 cm at its<br />

widest part (in Periplaneta australasiae). It extends back<br />

to the fourth or fifth abdominal segment, crowding the<br />

other organs and distending the intersegmental membranes.<br />

A meal may be retained in the crop for several<br />

days (Abbott, 1926; Cornwell, 1968). Solid food is also retained<br />

in the hindgut of starving P. americana for as long<br />

as 100 hr, although the normal transit time is about 20 hr<br />

(Bignell, 1981); this delay likely allows microbial biota to<br />

more thoroughly degrade some of the substrates present,<br />

particularly fiber. The functional significance of intestinal<br />

symbionts increases in times of food deficiency and helps<br />

to maintain a broad nutritional versatility (Zurek, 1997).<br />

A starving cockroach is thus indebted to its microbial<br />

partners on two counts: first, for eking out all possible nutrients<br />

in the hindgut, and second, for mobilizing uric<br />

acid stored in the fat body (Chapter 5). When food is<br />

again made available, starved P. americana binge. After<br />

starving for 13 days the amount of food consumed rose<br />

to five times the normal level, then leveled off after approximately<br />

20 days. Greater consumption was accomplished<br />

by larger and longer meals, not by increasing the<br />

number of foraging trips (Rollo, 1984a).<br />

PLANT-BASED FOOD<br />

There is little evidence that any cockroach species is able<br />

to subsist solely on the mature green leaves of vascular<br />

plants. There are reports of occasional herbivory, such as<br />

that of Crowell (1946), who noted that the small, round<br />

leaves of the aquatic plant Jussiaca are included in the diet<br />

of Epilampra maya. Often, cockroaches that appear to be<br />

feeding on green leaves are actually eating either a small,<br />

dead portion at the leaf edge or around a hole, or other<br />

material on the leaf (WJB, unpubl. obs.). To test the extent<br />

to which tropical cockroaches include fresh vegetation<br />

in their diets, WJB set up a series of two-choice tests<br />

in laboratory cages at La Selva Biological Station in Costa<br />

Rica. Ten species of cockroaches were tested: Capucina<br />

sp., Cariblatta imitans, Epilampra involucris, Ep. rothi, Ep.<br />

unistilata, Latiblattella sp., Imblattella impar, Nahublattella<br />

sp., Nesomylacris sp., and X. hamata. The insects were<br />

offered a choice of green leaves versus dead leaves of the<br />

same plant species; only leaves eaten readily by local Or-<br />

66 COCKROACHES