Cockroache; Ecology, behavior & history - W.J. Bell

Cockroache; Ecology, behavior & history - W.J. Bell

Cockroache; Ecology, behavior & history - W.J. Bell

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

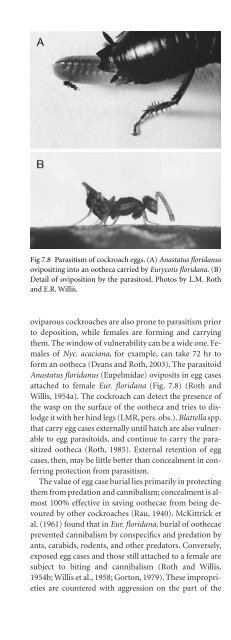

Fig 7.8 Parasitism of cockroach eggs. (A) Anastatus floridanus<br />

ovipositing into an ootheca carried by Eurycotis floridana. (B)<br />

Detail of oviposition by the parasitoid. Photos by L.M. Roth<br />

and E.R. Willis.<br />

oviparous cockroaches are also prone to parasitism prior<br />

to deposition, while females are forming and carrying<br />

them. The window of vulnerability can be a wide one. Females<br />

of Nyc. acaciana, for example, can take 72 hr to<br />

form an ootheca (Deans and Roth, 2003). The parasitoid<br />

Anastatus floridanus (Eupelmidae) oviposits in egg cases<br />

attached to female Eur. floridana (Fig. 7.8) (Roth and<br />

Willis, 1954a). The cockroach can detect the presence of<br />

the wasp on the surface of the ootheca and tries to dislodge<br />

it with her hind legs (LMR, pers. obs.). Blattella spp.<br />

that carry egg cases externally until hatch are also vulnerable<br />

to egg parasitoids, and continue to carry the parasitized<br />

ootheca (Roth, 1985). External retention of egg<br />

cases, then, may be little better than concealment in conferring<br />

protection from parasitism.<br />

The value of egg case burial lies primarily in protecting<br />

them from predation and cannibalism; concealment is almost<br />

100% effective in saving oothecae from being devoured<br />

by other cockroaches (Rau, 1940). McKittrick et<br />

al. (1961) found that in Eur. floridana, burial of oothecae<br />

prevented cannibalism by conspecifics and predation by<br />

ants, carabids, rodents, and other predators. Conversely,<br />

exposed egg cases and those still attached to a female are<br />

subject to biting and cannibalism (Roth and Willis,<br />

1954b; Willis et al., 1958; Gorton, 1979). These improprieties<br />

are countered with aggression on the part of the<br />

mother. Female P. brunnea, P. americana, and Paratemnopteryx<br />

couloniana drive other females away from exposed<br />

oothecae (Haber, 1920; Edmunds, 1957; Gorton,<br />

1979). Two <strong>behavior</strong>al classes of female can be distinguished<br />

in B. germanica; females carrying oothecae are<br />

more aggressive than females that had not yet formed<br />

them (Breed et al., 1975). Aggressive <strong>behavior</strong> is favored<br />

despite its attendant risks, given that one nip taken from<br />

an ootheca can result in the death of the entire clutch<br />

from desiccation (Roth and Willis, 1955b).<br />

Ovoviviparity is viewed as a solution to this constant<br />

battle against predators and parasites, and is thought to<br />

have appeared in the Mesozoic as an evolutionary response<br />

to cockroach enemies that first appeared during<br />

that time (Vishniakova, 1968). Parasitoids have not been<br />

detected in the oothecae of ovoviviparous blaberids<br />

(LMR, pers. obs.). The eggs are exposed to the environment<br />

for only the brief period of time between formation<br />

of the ootheca and its subsequent retraction into the<br />

body, allowing only a narrow time frame for parasitoid<br />

oviposition. Once in this enemy free space, the eggs are<br />

subject only to “the vicissitudes that beset the mother”<br />

(Roth and Willis, 1954b). Nonetheless, nymphs of ovoviviparous<br />

cockroaches are at risk from cannibalism at the<br />

time of hatch. Attempts by conspecifics to eat the hatchlings<br />

as the female ejects the ootheca have been noted and<br />

may include pulling the still attached egg case away from<br />

the mother (Willis et al., 1958). We note, however, that<br />

laboratory observations of cannibalism in cockroaches of<br />

any reproductive mode may be of little consequence in<br />

natural populations, with the exception of highly gregarious<br />

species like cave dwellers. Females of at least one<br />

species of the latter are known to be choosy about where<br />

they expel their neonates. Darlington (1970) reported<br />

that pregnant females of Eub. posticus preferred one<br />

chamber of the Tamana cave for giving birth, and migrated<br />

into that chamber from other parts of the cave.<br />

Defense against pathogens as agents of egg mortality is<br />

unstudied, despite the disease-conducive environments<br />

typical of cockroaches.<br />

Parental Costs<br />

Indirect reproductive costs of oviparity in cockroaches<br />

include the time, energy, and predation risks involved in<br />

concealing the ootheca in the environment and the metabolic<br />

expense of producing a protective oothecal case.<br />

The case consists primarily of quinone-tanned protein<br />

(Brunet and Kent, 1955) (Table 4.5), much of which can<br />

be recovered after hatch if the parent or neonates eat the<br />

embryonic membranes, unviable eggs, and the oothecal<br />

case after hatch (Roth and Willis, 1954b; Willis et al.,<br />

1958). In several species of cockroaches, oothecal predation<br />

by adults and the ingestion of oothecal cases after<br />

REPRODUCTION 127