Interim Report - TEEB

Interim Report - TEEB

Interim Report - TEEB

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

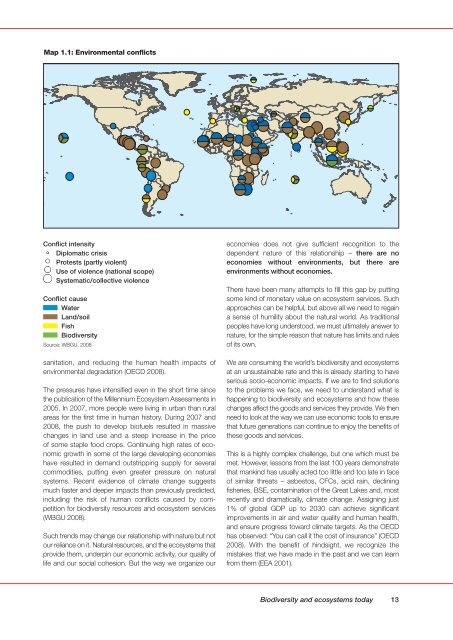

Map 1.1: Environmental conflicts<br />

Conflict intensity<br />

Diplomatic crisis<br />

Protests (partly violent)<br />

Use of violence (national scope)<br />

Systematic/collective violence<br />

Conflict cause<br />

Water<br />

Land/soil<br />

Fish<br />

Biodiversity<br />

Source: WBGU, 2008<br />

sanitation, and reducing the human health impacts of<br />

environmental degradation (OECD 2008).<br />

The pressures have intensified even in the short time since<br />

the publication of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessments in<br />

2005. In 2007, more people were living in urban than rural<br />

areas for the first time in human history. During 2007 and<br />

2008, the push to develop biofuels resulted in massive<br />

changes in land use and a steep increase in the price<br />

of some staple food crops. Continuing high rates of economic<br />

growth in some of the large developing economies<br />

have resulted in demand outstripping supply for several<br />

commodities, putting even greater pressure on natural<br />

systems. Recent evidence of climate change suggests<br />

much faster and deeper impacts than previously predicted,<br />

including the risk of human conflicts caused by competition<br />

for biodiversity resources and ecosystem services<br />

(WBGU 2008).<br />

Such trends may change our relationship with nature but not<br />

our reliance on it. Natural resources, and the ecosystems that<br />

provide them, underpin our economic activity, our quality of<br />

life and our social cohesion. But the way we organize our<br />

economies does not give sufficient recognition to the<br />

dependent nature of this relationship – there are no<br />

economies without environments, but there are<br />

environments without economies.<br />

There have been many attempts to fill this gap by putting<br />

some kind of monetary value on ecosystem services. Such<br />

approaches can be helpful, but above all we need to regain<br />

a sense of humility about the natural world. As traditional<br />

peoples have long understood, we must ultimately answer to<br />

nature, for the simple reason that nature has limits and rules<br />

of its own.<br />

We are consuming the world’s biodiversity and ecosystems<br />

at an unsustainable rate and this is already starting to have<br />

serious socio-economic impacts. If we are to find solutions<br />

to the problems we face, we need to understand what is<br />

happening to biodiversity and ecosystems and how these<br />

changes affect the goods and services they provide. We then<br />

need to look at the way we can use economic tools to ensure<br />

that future generations can continue to enjoy the benefits of<br />

these goods and services.<br />

This is a highly complex challenge, but one which must be<br />

met. However, lessons from the last 100 years demonstrate<br />

that mankind has usually acted too little and too late in face<br />

of similar threats – asbestos, CFCs, acid rain, declining<br />

fisheries, BSE, contamination of the Great Lakes and, most<br />

recently and dramatically, climate change. Assigning just<br />

1% of global GDP up to 2030 can achieve significant<br />

improvements in air and water quality and human health,<br />

and ensure progress toward climate targets. As the OECD<br />

has observed: “You can call it the cost of insurance” (OECD<br />

2008). With the benefit of hindsight, we recognize the<br />

mistakes that we have made in the past and we can learn<br />

from them (EEA 2001).<br />

Biodiversity and ecosystems today<br />

13