Interim Report - TEEB

Interim Report - TEEB

Interim Report - TEEB

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

attempts (Pattanayak and Kramer 2001, Gueorguieva and<br />

Bolt 2003, Munasinghe 2001, Benhin and Barbier 2001), this<br />

is still very much an area of ongoing research. Secondly, most<br />

of the valuation evidence comes from individual case studies<br />

concerning a particular ecosystem or species. Some studies<br />

have tried to make a global assessment of the world’s<br />

ecosystem services (e.g. Costanza et al. 1997) but, while<br />

they have been useful in raising attention and discussion,<br />

their results are controversial. Others focus at species or<br />

genera levels (Craft and Simpson 2001, Godoy et al. 2000,<br />

Pearce 2005, Small 2000). Any integral assessment on a<br />

broad scale raises substantial difficulties: how to define a<br />

coherent framework; how to deal with limitations in data; how<br />

to aggregate values to estimate the global impacts of largescale<br />

changes in ecosystems.<br />

In Phase II, we expect to rely on “benefit transfer” logic, i.e.<br />

using a value estimated in a particular site as an approximation<br />

of the value of the same ecosystem services in<br />

another site. Benefit transfer is easier for some homogeneous<br />

values (such as carbon absorption, which is a global good),<br />

than for others that are site-specific or context-dependent<br />

(such as watershed protection). However, we must recognize<br />

the trade-off between providing incomplete assessment on<br />

the one hand, and using inferred estimates (rather than<br />

primary research-based estimates) on the other.<br />

For both ecological and economic reasons, caution is<br />

needed when scaling up and aggregating values estimated<br />

from small marginal changes to assess the effects of large<br />

changes. Ecosystems often respond to stress in a non-linear<br />

fashion. Large changes in ecosystem size or condition may<br />

have abrupt effects on their functioning, which may not be<br />

extrapolated easily from the effect of small changes.<br />

Generally, as some ecosystem services decline substantially<br />

as we continue to use them, extrapolation of benefits should<br />

recognize and be limited by the “law of diminishing returns”.<br />

THE COSTS OF BIODIVERSITY LOSS<br />

There is a substantial body of evidence on the monetary<br />

values attached to biodiversity and ecosystems, and thus on<br />

the costs of their loss. A number of recent case studies and<br />

more general contributions have been received in reply to a<br />

call for evidence (see <strong>TEEB</strong> website http://ec.europa.eu/<br />

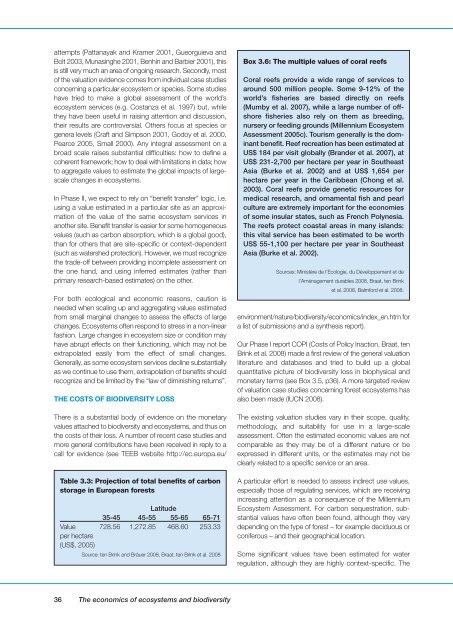

Table 3.3: Projection of total benefits of carbon<br />

storage in European forests<br />

Latitude<br />

35-45 45-55 55-65 65-71<br />

Value 728.56 1,272.85 468.60 253.33<br />

per hectare<br />

(US$, 2005)<br />

Source: ten Brink and Bräuer 2008, Braat, ten Brink et al. 2008<br />

Box 3.6: The multiple values of coral reefs<br />

Coral reefs provide a wide range of services to<br />

around 500 million people. Some 9-12% of the<br />

world’s fisheries are based directly on reefs<br />

(Mumby et al. 2007), while a large number of offshore<br />

fisheries also rely on them as breeding,<br />

nursery or feeding grounds (Millennium Ecosystem<br />

Assessment 2005c). Tourism generally is the dominant<br />

benefit. Reef recreation has been estimated at<br />

US$ 184 per visit globally (Brander et al. 2007), at<br />

US$ 231-2,700 per hectare per year in Southeast<br />

Asia (Burke et al. 2002) and at US$ 1,654 per<br />

hectare per year in the Caribbean (Chong et al.<br />

2003). Coral reefs provide genetic resources for<br />

medical research, and ornamental fish and pearl<br />

culture are extremely important for the economies<br />

of some insular states, such as French Polynesia.<br />

The reefs protect coastal areas in many islands:<br />

this vital service has been estimated to be worth<br />

US$ 55-1,100 per hectare per year in Southeast<br />

Asia (Burke et al. 2002).<br />

Sources: Ministère de l’Ecologie, du Développement et de<br />

l’Aménagement durables 2008, Braat, ten Brink<br />

et al. 2008, Balmford et al. 2008.<br />

environment/nature/biodiversity/economics/index_en.htm for<br />

a list of submissions and a synthesis report).<br />

Our Phase I report COPI (Costs of Policy Inaction, Braat, ten<br />

Brink et al. 2008) made a first review of the general valuation<br />

literature and databases and tried to build up a global<br />

quantitative picture of biodiversity loss in biophysical and<br />

monetary terms (see Box 3.5, p36). A more targeted review<br />

of valuation case studies concerning forest ecosystems has<br />

also been made (IUCN 2008).<br />

The existing valuation studies vary in their scope, quality,<br />

methodology, and suitability for use in a large-scale<br />

assessment. Often the estimated economic values are not<br />

comparable as they may be of a different nature or be<br />

expressed in different units, or the estimates may not be<br />

clearly related to a specific service or an area.<br />

A particular effort is needed to assess indirect use values,<br />

especially those of regulating services, which are receiving<br />

increasing attention as a consequence of the Millennium<br />

Ecosystem Assessment. For carbon sequestration, substantial<br />

values have often been found, although they vary<br />

depending on the type of forest – for example deciduous or<br />

coniferous – and their geographical location.<br />

Some significant values have been estimated for water<br />

regulation, although they are highly context-specific. The<br />

36 The economics of ecosystems and biodiversity