Interim Report - TEEB

Interim Report - TEEB

Interim Report - TEEB

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

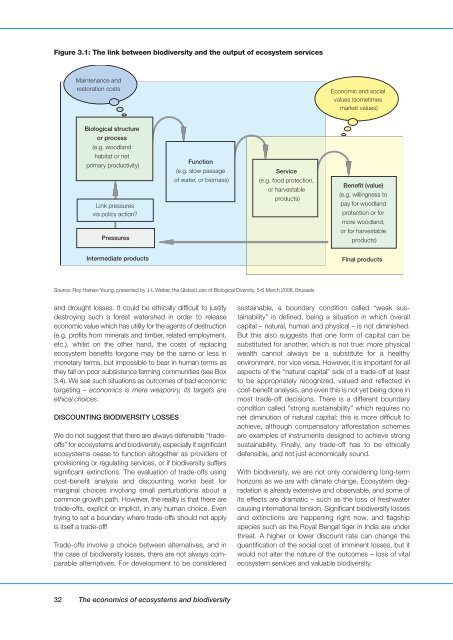

Figure 3.1: The link between biodiversity and the output of ecosystem services<br />

Maintenance and<br />

restoration costs<br />

Economic and social<br />

values (sometimes<br />

market values)<br />

Biological structure<br />

or process<br />

(e.g. woodland<br />

habitat or net<br />

primary productivity)<br />

Link pressures<br />

via policy action?<br />

Pressures<br />

Function<br />

(e.g. slow passage<br />

of water, or biomass)<br />

Service<br />

(e.g. food protection,<br />

or harvestable<br />

products)<br />

Benefit (value)<br />

(e.g. willingness to<br />

pay for woodland<br />

protection or for<br />

more woodland,<br />

or for harvestable<br />

products)<br />

Intermediate products<br />

Final products<br />

Source: Roy Haines-Young, presented by J-L Weber, the Global Loss of Biological Diversity, 5-6 March 2008, Brussels<br />

and drought losses. It could be ethically difficult to justify<br />

destroying such a forest watershed in order to release<br />

economic value which has utility for the agents of destruction<br />

(e.g. profits from minerals and timber, related employment,<br />

etc.), whilst on the other hand, the costs of replacing<br />

ecosystem benefits forgone may be the same or less in<br />

monetary terms, but impossible to bear in human terms as<br />

they fall on poor subsistence farming communities (see Box<br />

3.4). We see such situations as outcomes of bad economic<br />

targeting – economics is mere weaponry, its targets are<br />

ethical choices.<br />

DISCOUNTING BIODIVERSITY LOSSES<br />

We do not suggest that there are always defensible “tradeoffs”<br />

for ecosystems and biodiversity, especially if significant<br />

ecosystems cease to function altogether as providers of<br />

provisioning or regulating services, or if biodiversity suffers<br />

significant extinctions. The evaluation of trade-offs using<br />

cost-benefit analysis and discounting works best for<br />

marginal choices involving small perturbations about a<br />

common growth path. However, the reality is that there are<br />

trade-offs, explicit or implicit, in any human choice. Even<br />

trying to set a boundary where trade-offs should not apply<br />

is itself a trade-off!<br />

Trade-offs involve a choice between alternatives, and in<br />

the case of biodiversity losses, there are not always comparable<br />

alternatives. For development to be considered<br />

sustainable, a boundary condition called “weak sustainability”<br />

is defined, being a situation in which overall<br />

capital – natural, human and physical – is not diminished.<br />

But this also suggests that one form of capital can be<br />

substituted for another, which is not true: more physical<br />

wealth cannot always be a substitute for a healthy<br />

environment, nor vice versa. However, it is important for all<br />

aspects of the “natural capital” side of a trade-off at least<br />

to be appropriately recognized, valued and reflected in<br />

cost-benefit analysis, and even this is not yet being done in<br />

most trade-off decisions. There is a different boundary<br />

condition called “strong sustainability” which requires no<br />

net diminution of natural capital: this is more difficult to<br />

achieve, although compensatory afforestation schemes<br />

are examples of instruments designed to achieve strong<br />

sustainability. Finally, any trade-off has to be ethically<br />

defensible, and not just economically sound.<br />

With biodiversity, we are not only considering long-term<br />

horizons as we are with climate change. Ecosystem degradation<br />

is already extensive and observable, and some of<br />

its effects are dramatic – such as the loss of freshwater<br />

causing international tension. Significant biodiversity losses<br />

and extinctions are happening right now, and flagship<br />

species such as the Royal Bengal tiger in India are under<br />

threat. A higher or lower discount rate can change the<br />

quantification of the social cost of imminent losses, but it<br />

would not alter the nature of the outcomes – loss of vital<br />

ecosystem services and valuable biodiversity.<br />

32 The economics of ecosystems and biodiversity