Army - Kicking Tires On Jltv

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

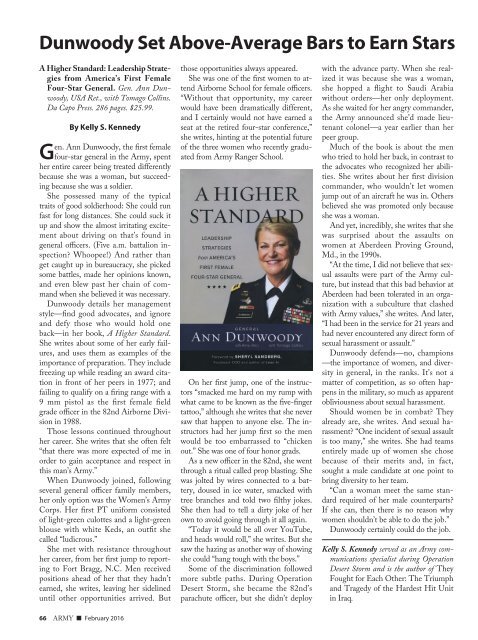

Dunwoody Set Above-Average Bars to Earn Stars<br />

A Higher Standard: Leadership Strategies<br />

from America’s First Female<br />

Four-Star General. Gen. Ann Dunwoody,<br />

USA Ret., with Tomago Collins.<br />

Da Capo Press. 286 pages. $25.99.<br />

By Kelly S. Kennedy<br />

Gen. Ann Dunwoody, the first female<br />

four-star general in the <strong>Army</strong>, spent<br />

her entire career being treated differently<br />

because she was a woman, but succeeding<br />

because she was a soldier.<br />

She possessed many of the typical<br />

traits of good soldierhood: She could run<br />

fast for long distances. She could suck it<br />

up and show the almost irritating excitement<br />

about driving on that’s found in<br />

general officers. (Five a.m. battalion inspection?<br />

Whoopee!) And rather than<br />

get caught up in bureaucracy, she picked<br />

some battles, made her opinions known,<br />

and even blew past her chain of command<br />

when she believed it was necessary.<br />

Dunwoody details her management<br />

style—find good advocates, and ignore<br />

and defy those who would hold one<br />

back—in her book, A Higher Standard.<br />

She writes about some of her early failures,<br />

and uses them as examples of the<br />

importance of preparation. They include<br />

freezing up while reading an award citation<br />

in front of her peers in 1977; and<br />

failing to qualify on a firing range with a<br />

9 mm pistol as the first female field<br />

grade officer in the 82nd Airborne Division<br />

in 1988.<br />

Those lessons continued throughout<br />

her career. She writes that she often felt<br />

“that there was more expected of me in<br />

order to gain acceptance and respect in<br />

this man’s <strong>Army</strong>.”<br />

When Dunwoody joined, following<br />

several general officer family members,<br />

her only option was the Women’s <strong>Army</strong><br />

Corps. Her first PT uniform consisted<br />

of light-green culottes and a light-green<br />

blouse with white Keds, an outfit she<br />

called “ludicrous.”<br />

She met with resistance throughout<br />

her career, from her first jump to reporting<br />

to Fort Bragg, N.C. Men received<br />

positions ahead of her that they hadn’t<br />

earned, she writes, leaving her sidelined<br />

until other opportunities arrived. But<br />

those opportunities always appeared.<br />

She was one of the first women to attend<br />

Airborne School for female officers.<br />

“Without that opportunity, my career<br />

would have been dramatically different,<br />

and I certainly would not have earned a<br />

seat at the retired four-star conference,”<br />

she writes, hinting at the potential future<br />

of the three women who recently graduated<br />

from <strong>Army</strong> Ranger School.<br />

<strong>On</strong> her first jump, one of the instructors<br />

“smacked me hard on my rump with<br />

what came to be known as the five-finger<br />

tattoo,” although she writes that she never<br />

saw that happen to anyone else. The instructors<br />

had her jump first so the men<br />

would be too embarrassed to “chicken<br />

out.” She was one of four honor grads.<br />

As a new officer in the 82nd, she went<br />

through a ritual called prop blasting. She<br />

was jolted by wires connected to a battery,<br />

doused in ice water, smacked with<br />

tree branches and told two filthy jokes.<br />

She then had to tell a dirty joke of her<br />

own to avoid going through it all again.<br />

“Today it would be all over YouTube,<br />

and heads would roll,” she writes. But she<br />

saw the hazing as another way of showing<br />

she could “hang tough with the boys.”<br />

Some of the discrimination followed<br />

more subtle paths. During Operation<br />

Desert Storm, she became the 82nd’s<br />

parachute officer, but she didn’t deploy<br />

with the advance party. When she realized<br />

it was because she was a woman,<br />

she hopped a flight to Saudi Arabia<br />

without orders—her only deployment.<br />

As she waited for her angry commander,<br />

the <strong>Army</strong> announced she’d made lieutenant<br />

colonel—a year earlier than her<br />

peer group.<br />

Much of the book is about the men<br />

who tried to hold her back, in contrast to<br />

the advocates who recognized her abilities.<br />

She writes about her first division<br />

commander, who wouldn’t let women<br />

jump out of an aircraft he was in. Others<br />

believed she was promoted only because<br />

she was a woman.<br />

And yet, incredibly, she writes that she<br />

was surprised about the assaults on<br />

women at Aberdeen Proving Ground,<br />

Md., in the 1990s.<br />

“At the time, I did not believe that sexual<br />

assaults were part of the <strong>Army</strong> culture,<br />

but instead that this bad behavior at<br />

Aberdeen had been tolerated in an organization<br />

with a subculture that clashed<br />

with <strong>Army</strong> values,” she writes. And later,<br />

“I had been in the service for 21 years and<br />

had never encountered any direct form of<br />

sexual harassment or assault.”<br />

Dunwoody defends—no, champions<br />

—the importance of women, and diversity<br />

in general, in the ranks. It’s not a<br />

matter of competition, as so often happens<br />

in the military, so much as apparent<br />

obliviousness about sexual harassment.<br />

Should women be in combat? They<br />

already are, she writes. And sexual harassment?<br />

“<strong>On</strong>e incident of sexual assault<br />

is too many,” she writes. She had teams<br />

entirely made up of women she chose<br />

because of their merits and, in fact,<br />

sought a male candidate at one point to<br />

bring diversity to her team.<br />

“Can a woman meet the same standard<br />

required of her male counterparts?<br />

If she can, then there is no reason why<br />

women shouldn’t be able to do the job.”<br />

Dunwoody certainly could do the job.<br />

Kelly S. Kennedy served as an <strong>Army</strong> communications<br />

specialist during Operation<br />

Desert Storm and is the author of They<br />

Fought for Each Other: The Triumph<br />

and Tragedy of the Hardest Hit Unit<br />

in Iraq.<br />

66 ARMY ■ February 2016