Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

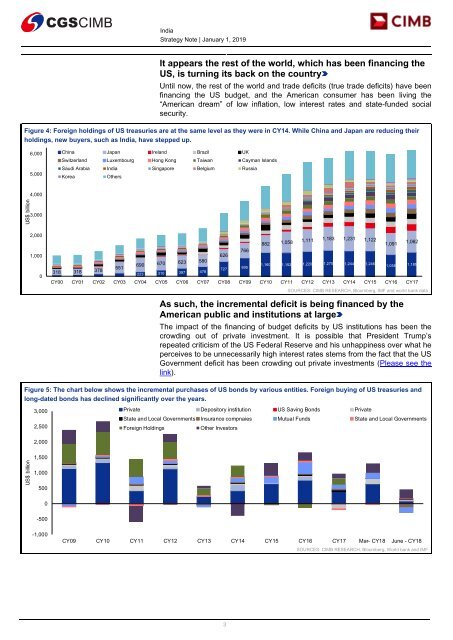

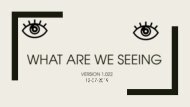

Thursday, 3 January 2019 Page 1<br />

For important disclosures please refer to page 16.<br />

Christopher Wood christopher.wood@clsa.com +852 2600 8516<br />

Asset prices and the Fed<br />

Verbier<br />

How resilient is the American economy to monetary tightening? This is one of the questions posed<br />

in the new Asia Maxima quarterly (see Asia Maxima – Trade and tightening, 2 January 2019). GREED &<br />

fear’s base case has been that the American economy reverts to trend growth in 2019 following last<br />

year’s fiscally-driven acceleration. This would suggest a growth rate of 2.2%, which is the average<br />

growth rate since the recovery began in 2009 prior to the tax cut last year.<br />

Still the risk of an uglier outcome will rise if there is a nasty decline in asset prices. This is because in<br />

a post quantitative easing world, the normal causality taught in economic textbooks has reversed. By<br />

which GREED & fear means that asset prices now drive economies rather than the reverse.<br />

This has now become a highly-relevant point for investors, as asset prices declined last year as<br />

Federal Reserve quantitative tightening kicked in. The Fed’s balance sheet contracted by US$373bn<br />

in 2018 (see Figure 1). Investors should not assume this is a coincidence. For now at least the Fed’s<br />

quantitative tightening is set to continue at a pace of US$50bn a month, while the ECB confirmed in<br />

December it will stop quantitative easing from the end of 2018, even though the growth outlook in<br />

its region has deteriorated of late. Still, the ECB balance sheet will not shrink from its current size of<br />

€4.67tn, given that maturing bonds will continue to be reinvested.<br />

Figure 1<br />

Federal Reserve balance sheet contraction plan<br />

5.0<br />

4.5<br />

4.0<br />

3.5<br />

3.0<br />

2.5<br />

2.0<br />

1.5<br />

1.0<br />

0.5<br />

0.0<br />

(US$tn)<br />

Source: CLSA, Federal Reserve<br />

Other assets<br />

Agency debt & MBS<br />

Treasury securities<br />

Jan 07<br />

May 07<br />

Sep 07<br />

Jan 08<br />

May 08<br />

Sep 08<br />

Jan 09<br />

May 09<br />

Sep 09<br />

Jan 10<br />

May 10<br />

Sep 10<br />

Jan 11<br />

May 11<br />

Sep 11<br />

Jan 12<br />

May 12<br />

Sep 12<br />

Jan 13<br />

May 13<br />

Sep 13<br />

Jan 14<br />

May 14<br />

Sep 14<br />

Jan 15<br />

May 15<br />

Sep 15<br />

Jan 16<br />

May 16<br />

Sep 16<br />

Jan 17<br />

May 17<br />

Sep 17<br />

Jan 18<br />

May 18<br />

Sep 18<br />

Jan 19<br />

May 19<br />

Sep 19<br />

By contrast, the Fed’s balance sheet has already shrunk by US$396bn since September 2017, a<br />

decline of 9% since the balance-sheet contraction began in October 2017. At its peak, the balance<br />

sheet totalled US$4.5tn. If the Fed continues to shrink the balance sheet by the scheduled US$50bn<br />

a month during the coming year, it will have declined by a further 14.7% by the end of 2019.<br />

In such a context of accelerating tightening, credit spreads now need to be watched closely for signs<br />

of rising stress in the system. For they will be the signal of an uglier decline in asset prices than just<br />

a correction of stock market excesses, in terms of a derating of high PE growth stocks.