- Page 2 and 3:

#* "LI B R.AR.Y' OF THE UNIVERSITY

- Page 5:

Publications OF FIELD MUSEUM OF NAT

- Page 9:

Field Museum of Natural History Pub

- Page 12 and 13:

iv Contents, \{ Page Cassia Pods an

- Page 14 and 15:

1 86 Sino-Iranica part of which hav

- Page 16 and 17:

1 88 Sino-Iranica most advanced and

- Page 18 and 19:

ioo Sino-Iranica number of addition

- Page 20 and 21:

192 Sino-Iranica It has been my end

- Page 22 and 23:

194 Sino-Iranica scented mint is Va

- Page 24 and 25:

196 Sino-Iranica by the people of K

- Page 26 and 27:

198 Sino-Iranica Kamchatka, and the

- Page 28 and 29:

200 Sino-Iranica attribute Hu, it m

- Page 30 and 31:

202 Sino-Iranica some vaguely defin

- Page 32 and 33:

204 Sino-Iranica of important plant

- Page 34 and 35:

206 Sino-Iranica since his days Ori

- Page 36 and 37:

ALFALFA I. The earliest extant lite

- Page 38 and 39:

210 Sino-Iranica acted as mediators

- Page 40 and 41:

212 Sino-Iranica very well aware of

- Page 42 and 43:

214 Sino-Iranica *suk, stand for Za

- Page 44 and 45:

216 Sino-Iranica 3. Trigonella f&nu

- Page 46 and 47:

«i8 Sino-Iranica and Hemsley 1 giv

- Page 48 and 49:

THE GRAPE-VINE 2. The grape-vine (V

- Page 50 and 51:

222 SlNO-lRANICA age. 1 When the So

- Page 52 and 53:

224 Sino-Iranica vine, as we call i

- Page 54 and 55:

226 Sino-Iranica Hirth 1 endorsed K

- Page 56 and 57:

228 Sino-Iranica have applied a Per

- Page 58 and 59:

t$o Sino-Iranica of grape. Accordin

- Page 60 and 61:

232 Sino-Iranica they do not know i

- Page 62 and 63:

«34 Sino-Iranica A recipe for maki

- Page 64 and 65:

236 Sino-Iranica distilled from the

- Page 66 and 67:

«38 Sino-Iranica wine in the same

- Page 68 and 69:

240 Sino-Iranica ported from Pa-lai

- Page 70 and 71:

242 Tavernier 1 Sino-Iranica states

- Page 72 and 73:

244 Sino-Iranica but is an entirely

- Page 74 and 75:

THE PISTACHIO 3. Pistacia is a genu

- Page 76 and 77:

248 Sino-Iranica ?). Persians 3£ $

- Page 78 and 79:

t$o Sino-Iranica gwan, gwana, for P

- Page 80 and 81:

252 Sino-Iranica Again, the Persian

- Page 82 and 83: THE WALNUT 4. The Buddhist dictiona

- Page 84 and 85: 256 Sino-Iranica The New-Persian na

- Page 86 and 87: 258 Sino-Iranica B.C." 1 In Hehn's

- Page 88 and 89: 260 Sino-Iranica of Su Tsun 1£ $t

- Page 90 and 91: 262 Sino-Iranica much. The tree is

- Page 92 and 93: 264 Sino-Iranica 3$i # 13. * Anothe

- Page 94 and 95: *66 Sino-Iranica all the district a

- Page 96 and 97: 268 Sino-Iranica tion is quite to t

- Page 98 and 99: tyo Sino-Iranica is one of the most

- Page 100 and 101: 272 Sino-Iranica specific case apt

- Page 102 and 103: a74 Sino-Iranica abbreviated name o

- Page 104 and 105: THE POMEGRANATE 5. A. de Candolle 1

- Page 106 and 107: 278 Sino-Iranica They take out of t

- Page 108 and 109: 280 Sino-Iranica are the particular

- Page 110 and 111: 282 Sino-Iranica are smaller and pa

- Page 112 and 113: 284 Sino-Iranica dana ("grain, berr

- Page 114 and 115: 286 Sino-Iranica likewise from Iran

- Page 116 and 117: SESAME AND FLAX 6. In A. de Candoll

- Page 118 and 119: 290 Sino-Iranica Herodotus 1 emphas

- Page 120 and 121: 292 Sino-Iranica San-tan Ji $& (sou

- Page 122 and 123: [ 294 Sino-Iranica (Iranians and In

- Page 124 and 125: 296 Sino-Iranica jS ffc (Japanese n

- Page 126 and 127: 298 Sino-Iranica the character swi

- Page 128 and 129: THE CUCUMBER 9. Another dogma of th

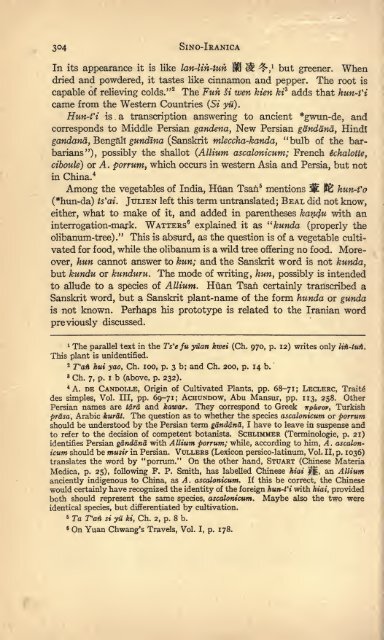

- Page 130 and 131: CHIVE, ONION, AND SHALLOT 10. Altho

- Page 134 and 135: 306 Sino-Iranica fix approximately

- Page 136 and 137: 308 Sino-Iranica Ming, 1 which stat

- Page 138 and 139: 310 Sino-Iranica that our genus Cur

- Page 140 and 141: 312 Sino-Iranica fron." 1 It is bor

- Page 142 and 143: 314 Sino-Iranica £m and ma-lu, are

- Page 144 and 145: 316 Sino-Iranica with this dye. Abu

- Page 146 and 147: 318 Sino-Iranica The last clause me

- Page 148 and 149: 320 Sino-Iranica maunds, or 3200 Kh

- Page 150 and 151: 322 Sino-Iranica the reproduction o

- Page 152 and 153: SAFFLOWER that the cultivation of (

- Page 154 and 155: 326 Sino-Iranica f? J£ $t, in his

- Page 156 and 157: 328 Sino-Iranica make abundant use

- Page 158 and 159: 330 Sino-Iranica that at this early

- Page 160 and 161: 332 Sino-Iranica Sanskrit mallikd (

- Page 162 and 163: HENNA 19. It is well known that the

- Page 164 and 165: 336 Sino-Iranica H Ht 1 by Cou Mi f

- Page 166 and 167: 338 Sino-Iranica seems more likely

- Page 168 and 169: 340 Sino-Iranica cattle and horses.

- Page 170 and 171: 342 Sino-Iranica exclusively as a t

- Page 172 and 173: 344 Sino-Iranica of Persia, furnish

- Page 174 and 175: 346 Sino-Iranica bling those of an

- Page 176 and 177: 348 Sino-Iranica in India guzangabi

- Page 178 and 179: 350 Sino-Iranica yield, under the p

- Page 180 and 181: 352 Sino-Iranica according to his s

- Page 182 and 183:

354 Sino-Iranica f&tidum). 1 It is

- Page 184 and 185:

356 Sino-Iranica was Garcia da Orta

- Page 186 and 187:

358 Sino-Iranica pots and drinking

- Page 188 and 189:

360 Sino-Iranica pie $wo about a.d.

- Page 190 and 191:

362 when the Mongols Sino-Iranica i

- Page 192 and 193:

364 Sino-Iranica by Theophrastus: 1

- Page 194 and 195:

366 Sino-Iranica countered by Buhse

- Page 196 and 197:

368 Sino-Iranica where they are sty

- Page 198 and 199:

INDIGO 25. As indicated by our word

- Page 200 and 201:

RICE 26. While rice is at present a

- Page 202 and 203:

PEPPER 27. The pepper-plant (hu tsi

- Page 204 and 205:

SUGAR 28. The sugar-cane (Saccharum

- Page 206 and 207:

MYROBALAN 29. The myrobalan Termina

- Page 208 and 209:

BRASSICA 32. Of the two species of

- Page 210 and 211:

382 Sino-Iranica "Man-tsin occurs [

- Page 212 and 213:

384 Sino-Iranica carui), however, i

- Page 214 and 215:

386 Sino-Iranica and first occurs i

- Page 216 and 217:

388 Sino-Iranica a number of hetero

- Page 218 and 219:

390 Sino-Iranica giraffes. 1 It lik

- Page 220 and 221:

THE SPINACH 36. In regard to the sp

- Page 222 and 223:

394 Sino-Iranica Emperor T'ai Tsun

- Page 224 and 225:

396 Sino-Iranica espinaca, Portugue

- Page 226 and 227:

398 Sino-Iranica or Palaka 1 as the

- Page 228 and 229:

400 Sino-Iranica Caspian Sea and Pe

- Page 230 and 231:

402 Sino-Iranica kit." 1 These are

- Page 232 and 233:

404 Sino-Iranica gathered, and eith

- Page 234 and 235:

406 Sino-Iranica province of Gujara

- Page 236 and 237:

408 Sino-Iranica China. Bunge says

- Page 238 and 239:

THE FIG 42. The fig (Ficus carted)

- Page 240 and 241:

412 Sino-Iranica fruit on its inter

- Page 242 and 243:

414 Sino-Iranica comprises nearly a

- Page 244 and 245:

416 Sino-Iranica Schlimmer 1 says t

- Page 246 and 247:

4i 8 Sino-Iranica pao pen is'ao (wr

- Page 248 and 249:

CASSIA PODS AND CAROB 44. In his Pe

- Page 250 and 251:

422 Sino-Iranica When I had establi

- Page 252 and 253:

424 Sino-Iranica passage: the two t

- Page 254 and 255:

426 Sino-Iranica extent, west of th

- Page 256 and 257:

428 Sino-Iranica loan-word), denoti

- Page 258 and 259:

430 Sino-Iranica qfofalsmdn is deri

- Page 260 and 261:

432 Sino-Iranica are placed beneath

- Page 262 and 263:

434 Sino-Iranica Ferdinand Verbiest

- Page 264 and 265:

436 Sino-Iranica connected with our

- Page 266 and 267:

THE WATER-MELON 49. This Cucurbitac

- Page 268 and 269:

440 Sino-Iranica The man who introd

- Page 270 and 271:

442 Sino-Iranica fruit is inferior

- Page 272 and 273:

444 Sino-Iranica call it Batiec Ind

- Page 274 and 275:

FENUGREEK 50. In regard to the fenu

- Page 276 and 277:

NUX-VOMICA 51. The nux-vomica or st

- Page 278 and 279:

45° Sino-Iranica Services of Cochi

- Page 280 and 281:

452 tinued to cultivate it in Engla

- Page 282 and 283:

454 Sino-Iranica name HaSqdqul, whi

- Page 284 and 285:

456 Sino-Ira*tica According to Stua

- Page 286 and 287:

458 Sino-Iranica strongest evidence

- Page 288 and 289:

460 Sino-Iranica from a tree growin

- Page 290 and 291:

462 Sino-Iranica Theophrastus 1 men

- Page 292 and 293:

464 Sino-Iranica K'un-lun of the So

- Page 294 and 295:

466 Sino-Iranica product may be exp

- Page 296 and 297:

THE MALAYAN PO-SE AND ITS PRODUCTS

- Page 298 and 299:

470 Sino-Iranica and people P'o-lo-

- Page 300 and 301:

472 Sino-Iranica had brought tribut

- Page 302 and 303:

474 Sino-Iranica Lambesi; i.e., Bes

- Page 304 and 305:

476 Sino-Iranica king) 1 there are

- Page 306 and 307:

478 • Sino-Iranica The question h

- Page 308 and 309:

480 Sino-Iranica the countries beyo

- Page 310 and 311:

482 " l :2c M 3=L . Sino-Iranica Ac

- Page 312 and 313:

484 Sino-Iranica also in Ho-cou & '

- Page 314 and 315:

486 Sino-Iranica that the character

- Page 316 and 317:

PERSIAN TEXTILES 69. Brocades, that

- Page 318 and 319:

490 Sino-Iranica is not part of the

- Page 320 and 321:

492 Sino-Iranica and the latter a f

- Page 322 and 323:

494 Sino-Iranica In the T'ang Annal

- Page 324 and 325:

496 Sino-Iranica Yuan H, Ibn Batata

- Page 326 and 327:

498 Sino-Iranica so that the Chines

- Page 328 and 329:

500 Sino-Iranica text to this effec

- Page 330 and 331:

502 Sino-Iranica study on the histo

- Page 332 and 333:

504 Sino-Iranica the Chinese. F. de

- Page 334 and 335:

506 Sino-Iranica be a product of K'

- Page 336 and 337:

508 Sino-Iranica The Tibetans appea

- Page 338 and 339:

510 Sino-Iranica The Ko ku yao lun

- Page 340 and 341:

512 Sino-Iranica swi H hi M st£ Wl

- Page 342 and 343:

514 Sino-Iranica to import the allo

- Page 344 and 345:

516 Sino-Iranica character pin has

- Page 346 and 347:

518 Sino-Iranica se-se of the T'ang

- Page 348 and 349:

520 Sino-Iranica Yun-nan Province.

- Page 350 and 351:

522 Sino-Iranica ninth and the tent

- Page 352 and 353:

524 Sino-Iranica Chinese learned of

- Page 354 and 355:

526 Pelliot. 1 Sino-Iranica by Pell

- Page 356 and 357:

528 Sino-Iranica of curing any dise

- Page 358 and 359:

530 Sino-Iranica tained in the Sui

- Page 360 and 361:

532 Sino-Iranica may justly be infe

- Page 362 and 363:

534 Sino-Iranica }ft ^ or Cu-wu Ek

- Page 364 and 365:

536 Sino-Iranica for staves, the sm

- Page 366 and 367:

538 Sino-Iranica nian, loan-word fr

- Page 368 and 369:

540 Sino-Iranica ("yellow plum")- 1

- Page 370 and 371:

542 Sino-Iranica The descriptions g

- Page 372 and 373:

544 Sino-Iranica or the attribution

- Page 374 and 375:

546 Sino-Iranica KokovT^ia, xauXtfe

- Page 376 and 377:

548 Sino-Iranica and Turkish, likew

- Page 378 and 379:

550 Sino-Iranica San-fu-ts'i (Palem

- Page 380 and 381:

552 Sino-Iranica judging from what

- Page 382 and 383:

554 Sino-Iranica sio, in the posthu

- Page 384 and 385:

556 Sino-Iranica ihelg as-sin ("Chi

- Page 386 and 387:

558 Sino-Iranica Karabacek and Hoer

- Page 388 and 389:

560 Sino-Iranica 1 paper bank-notes

- Page 390 and 391:

562 Sino-Iranica petits. . . . On l

- Page 392 and 393:

564 Sino-Iranica spread to Central

- Page 394 and 395:

566 Sino-Iranica cussed by me in tw

- Page 396 and 397:

568 Sino-Iranica _ The term pi-si h

- Page 398 and 399:

570 Sino-Iranica laws, that a Chine

- Page 400 and 401:

Appendix I IRANIAN ELEMENTS IN MONG

- Page 402 and 403:

574 Sino-Iranica possible to prove

- Page 404 and 405:

576 Sino-Iranica 22. Mongol Hkar, H

- Page 406 and 407:

578 Sino-Iranica Chinese Swi-hien ^

- Page 408 and 409:

Appendix III THE INDIAN ELEMENTS IN

- Page 410 and 411:

582 Sino-Iranica p. 54) explains th

- Page 412 and 413:

584 Sino-Iranica remedy." Achundow

- Page 414 and 415:

Appendix IV THE BASIL I propose to

- Page 416 and 417:

588 Sino-Iranica Ainslie, 1 the pla

- Page 418 and 419:

590 Sino-Iranica herb. As it is loc

- Page 420 and 421:

592 Sino-Iranica does not form part

- Page 422 and 423:

594 Sino-Iranica "exempt from taxes

- Page 424 and 425:

596 Sino-Iranica 18. pdVi is the co

- Page 427 and 428:

GENERAL INDEX The Index contains al

- Page 429 and 430:

Tang Annals, 469; nux-vomica of, 44

- Page 431 and 432:

Erdmann, F. v., 527. Esposito, M.,

- Page 433 and 434:

194-202; salt of the, 201; with ref

- Page 435 and 436:

Kwan yu ki, 201, 251, 341, 345, 489

- Page 437 and 438:

Mon-ku £i, 295. Mon Han lu, 229, 2

- Page 439 and 440:

Pott, F. A., 249, 370, 421, 503, 54

- Page 441 and 442:

Stuart, G. A., I95"i97. 200, 216, 2

- Page 443 and 444:

Ts'ai Lun, 563. Ts'ai Yin, 281 note

- Page 445 and 446:

Abrus precatorius 215 Acacia catech

- Page 447 and 448:

Jasminum officinale 329, 332 Jasmin

- Page 449 and 450:

INDEX OF WORDS Iranian, Indian, Mon

- Page 451 and 452:

yu-kin hiafi 314, 317 yu liu 282 yu

- Page 453 and 454:

jarak 404 kalgan 546 kaminan 465 ka

- Page 455 and 456:

palanka 397 pippala 435 pippall 374