THIS WEEK IN

THIS WEEK IN

THIS WEEK IN

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

N EWS<br />

F OCUS<br />

eases, says Hahn. “They will open up a lot of<br />

new applications,” Lo agrees.<br />

One major caveat is that the studies so far<br />

have only been able to detect mutations<br />

passed on by the father. Because there’s not<br />

yet a way to completely separate fetal DNA<br />

from the maternal DNA in a woman’s blood,<br />

it’s not possible to tell if a mutation possessed<br />

by the mother has been inherited by the fetus<br />

or if researchers are just seeing the mother’s<br />

DNA. One possible solution may be an epigenetic<br />

marker, such as methylated groups<br />

attached to a gene, that distinguishes fetal<br />

DNA from a mother’s. Lo’s group showed in<br />

2002 that they could make such a<br />

distinction. Another potential<br />

strategy is to use messenger<br />

RNA molecules produced<br />

only by the fetus and not the<br />

mother. Several groups have<br />

recently shown, for example,<br />

that RNA produced by placental<br />

genes can be detected in maternal<br />

blood.<br />

Seeing double<br />

Diagnosing Down syndrome<br />

noninvasively through fetal DNA is<br />

the big prize luring researchers. The potential<br />

demand for such a test is huge, says<br />

Boston University’s Charles Cantor, chief<br />

scientific officer of Sequenom Inc.,<br />

because the rate of Down syndrome is at<br />

least 1 in 270 for mothers over 35. Doctors<br />

can screen for the disorder in the first<br />

trimester by using ultrasound to measure<br />

the dimensions of the fetus’s neck and<br />

checking the levels of several protein markers<br />

in maternal blood; this combination<br />

picks up 85% of cases, albeit with a false<br />

positive rate of 2% to 6%. The International<br />

Down Syndrome Screening group last year<br />

called for this noninvasive strategy to be<br />

offered to all women, but a firm diagnosis<br />

still requires subsequent amniocentesis or<br />

CVS. The $1000 or more cost of these two<br />

tests limits routine use to women over 35,<br />

which means most Down syndrome births<br />

now occur in younger women.<br />

Yet while Down syndrome is easy to<br />

detect if fetal cells are in hand, it’s harder<br />

using cell-free DNA. The reason is that this<br />

condition is caused by an extra chromosome,<br />

rather than a mutation that can be detected<br />

with PCR. So far, for Down syndrome, fetal<br />

DNA can be used to only slightly improve<br />

screening: Overall fetal DNA levels are<br />

higher in women carrying fetuses with Down<br />

syndrome and some other aneuploidies.<br />

Adding a fetal DNA quantity test to other<br />

serum markers for Down syndrome would<br />

boost the detection rate from 81% to<br />

85%, Bianchi’s group has shown.<br />

Still, the real prize is a straightforward,<br />

noninvasive fetal DNA diagnostic for Down<br />

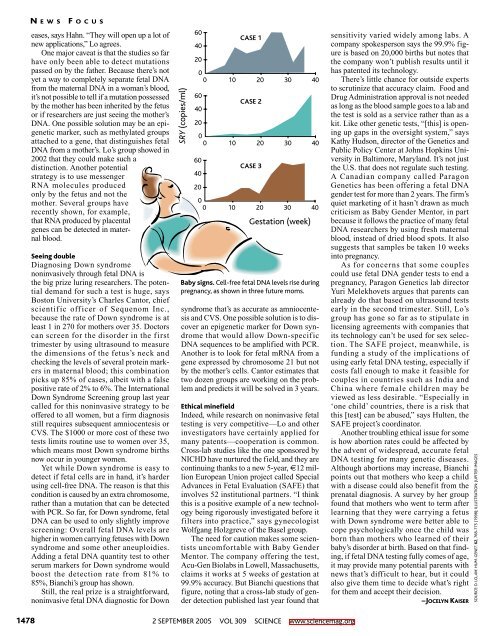

SRY (copies/ml)<br />

60<br />

40<br />

20<br />

0<br />

0 10 20 30 40<br />

60<br />

40<br />

60<br />

40<br />

CASE 1<br />

CASE 2<br />

20<br />

0<br />

0 10 20 30 40<br />

CASE 3<br />

20<br />

0<br />

0 10 20 30 40<br />

Gestation (week)<br />

Baby signs. Cell-free fetal DNA levels rise during<br />

pregnancy, as shown in three future moms.<br />

syndrome that’s as accurate as amniocentesis<br />

and CVS. One possible solution is to discover<br />

an epigenetic marker for Down syndrome<br />

that would allow Down-specific<br />

DNA sequences to be amplified with PCR.<br />

Another is to look for fetal mRNA from a<br />

gene expressed by chromosome 21 but not<br />

by the mother’s cells. Cantor estimates that<br />

two dozen groups are working on the problem<br />

and predicts it will be solved in 3 years.<br />

Ethical minefield<br />

Indeed, while research on noninvasive fetal<br />

testing is very competitive—Lo and other<br />

investigators have certainly applied for<br />

many patents—cooperation is common.<br />

Cross-lab studies like the one sponsored by<br />

NICHD have nurtured the field, and they are<br />

continuing thanks to a new 5-year, €12 million<br />

European Union project called Special<br />

Advances in Fetal Evaluation (SAFE) that<br />

involves 52 institutional partners. “I think<br />

this is a positive example of a new technology<br />

being rigorously investigated before it<br />

filters into practice,” says gynecologist<br />

Wolfgang Holzgreve of the Basel group.<br />

The need for caution makes some scientists<br />

uncomfortable with Baby Gender<br />

Mentor. The company offering the test,<br />

Acu-Gen Biolabs in Lowell, Massachusetts,<br />

claims it works at 5 weeks of gestation at<br />

99.9% accuracy. But Bianchi questions that<br />

figure, noting that a cross-lab study of gender<br />

detection published last year found that<br />

sensitivity varied widely among labs. A<br />

company spokesperson says the 99.9% figure<br />

is based on 20,000 births but notes that<br />

the company won’t publish results until it<br />

has patented its technology.<br />

There’s little chance for outside experts<br />

to scrutinize that accuracy claim. Food and<br />

Drug Administration approval is not needed<br />

as long as the blood sample goes to a lab and<br />

the test is sold as a service rather than as a<br />

kit. Like other genetic tests, “[this] is opening<br />

up gaps in the oversight system,” says<br />

Kathy Hudson, director of the Genetics and<br />

Public Policy Center at Johns Hopkins University<br />

in Baltimore, Maryland. It’s not just<br />

the U.S. that does not regulate such testing.<br />

A Canadian company called Paragon<br />

Genetics has been offering a fetal DNA<br />

gender test for more than 2 years. The firm’s<br />

quiet marketing of it hasn’t drawn as much<br />

criticism as Baby Gender Mentor, in part<br />

because it follows the practice of many fetal<br />

DNA researchers by using fresh maternal<br />

blood, instead of dried blood spots. It also<br />

suggests that samples be taken 10 weeks<br />

into pregnancy.<br />

As for concerns that some couples<br />

could use fetal DNA gender tests to end a<br />

pregnancy, Paragon Genetics lab director<br />

Yuri Melekhovets argues that parents can<br />

already do that based on ultrasound tests<br />

early in the second trimester. Still, Lo’s<br />

group has gone so far as to stipulate in<br />

licensing agreements with companies that<br />

its technology can’t be used for sex selection.<br />

The SAFE project, meanwhile, is<br />

funding a study of the implications of<br />

using early fetal DNA testing, especially if<br />

costs fall enough to make it feasible for<br />

couples in countries such as India and<br />

China where female children may be<br />

viewed as less desirable. “Especially in<br />

‘one child’ countries, there is a risk that<br />

this [test] can be abused,” says Hulten, the<br />

SAFE project’s coordinator.<br />

Another troubling ethical issue for some<br />

is how abortion rates could be affected by<br />

the advent of widespread, accurate fetal<br />

DNA testing for many genetic diseases.<br />

Although abortions may increase, Bianchi<br />

points out that mothers who keep a child<br />

with a disease could also benefit from the<br />

prenatal diagnosis. A survey by her group<br />

found that mothers who went to term after<br />

learning that they were carrying a fetus<br />

with Down syndrome were better able to<br />

cope psychologically once the child was<br />

born than mothers who learned of their<br />

baby’s disorder at birth. Based on that finding,<br />

if fetal DNA testing fully comes of age,<br />

it may provide many potential parents with<br />

news that’s difficult to hear, but it could<br />

also give them time to decide what’s right<br />

for them and accept their decision.<br />

–JOCELYN KAISER<br />

SOURCE: D. LO, AM. HUM. GENET. 62, 768-775 (1998); ILLUSTRATION: JUPITER IMAGES<br />

1478<br />

2 SEPTEMBER 2005 VOL 309 SCIENCE www.sciencemag.org