Smart & Good High Schools - The Flippen Group

Smart & Good High Schools - The Flippen Group

Smart & Good High Schools - The Flippen Group

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

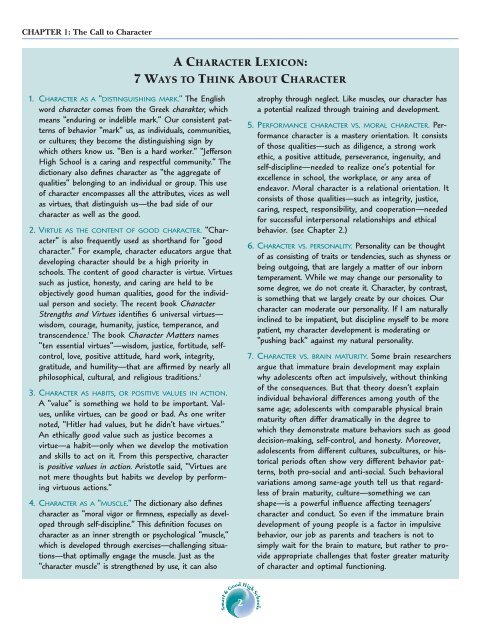

CHAPTER 1: <strong>The</strong> Call to CharacterA CHARACTER LEXICON:7 WAYS TO THINK ABOUT CHARACTER1. CHARACTER AS A “DISTINGUISHING MARK.” <strong>The</strong> Englishword character comes from the Greek charakter, whichmeans “enduring or indelible mark.” Our consistent patternsof behavior “mark” us, as individuals, communities,or cultures; they become the distinguishing sign bywhich others know us. “Ben is a hard worker.” “Jefferson<strong>High</strong> School is a caring and respectful community.” <strong>The</strong>dictionary also defines character as “the aggregate ofqualities” belonging to an individual or group. This useof character encompasses all the attributes, vices as wellas virtues, that distinguish us—the bad side of ourcharacter as well as the good.2. VIRTUE AS THE CONTENT OF GOOD CHARACTER. “Character”is also frequently used as shorthand for “goodcharacter.” For example, character educators argue thatdeveloping character should be a high priority inschools. <strong>The</strong> content of good character is virtue. Virtuessuch as justice, honesty, and caring are held to beobjectively good human qualities, good for the individualperson and society. <strong>The</strong> recent book CharacterStrengths and Virtues identifies 6 universal virtues—wisdom, courage, humanity, justice, temperance, andtranscendence. 1 <strong>The</strong> book Character Matters names“ten essential virtues”—wisdom, justice, fortitude, selfcontrol,love, positive attitude, hard work, integrity,gratitude, and humility—that are affirmed by nearly allphilosophical, cultural, and religious traditions. 23. CHARACTER AS HABITS, OR POSITIVE VALUES IN ACTION.A “value” is something we hold to be important. Values,unlike virtues, can be good or bad. As one writernoted, “Hitler had values, but he didn’t have virtues.”An ethically good value such as justice becomes avirtue—a habit—only when we develop the motivationand skills to act on it. From this perspective, characteris positive values in action. Aristotle said, “Virtues arenot mere thoughts but habits we develop by performingvirtuous actions.”4. CHARACTER AS A “MUSCLE.” <strong>The</strong> dictionary also definescharacter as “moral vigor or firmness, especially as developedthrough self-discipline.” This definition focuses oncharacter as an inner strength or psychological “muscle,”which is developed through exercises—challenging situations—thatoptimally engage the muscle. Just as the“character muscle” is strengthened by use, it can alsoatrophy through neglect. Like muscles, our character hasa potential realized through training and development.5. PERFORMANCE CHARACTER VS. MORAL CHARACTER. Performancecharacter is a mastery orientation. It consistsof those qualities—such as diligence, a strong workethic, a positive attitude, perseverance, ingenuity, andself-discipline—needed to realize one’s potential forexcellence in school, the workplace, or any area ofendeavor. Moral character is a relational orientation. Itconsists of those qualities—such as integrity, justice,caring, respect, responsibility, and cooperation—neededfor successful interpersonal relationships and ethicalbehavior. (see Chapter 2.)6. CHARACTER VS. PERSONALITY. Personality can be thoughtof as consisting of traits or tendencies, such as shyness orbeing outgoing, that are largely a matter of our inborntemperament. While we may change our personality tosome degree, we do not create it. Character, by contrast,is something that we largely create by our choices. Ourcharacter can moderate our personality. If I am naturallyinclined to be impatient, but discipline myself to be morepatient, my character development is moderating or“pushing back” against my natural personality.7. CHARACTER VS. BRAIN MATURITY. Some brain researchersargue that immature brain development may explainwhy adolescents often act impulsively, without thinkingof the consequences. But that theory doesn’t explainindividual behavioral differences among youth of thesame age; adolescents with comparable physical brainmaturity often differ dramatically in the degree towhich they demonstrate mature behaviors such as gooddecision-making, self-control, and honesty. Moreover,adolescents from different cultures, subcultures, or historicalperiods often show very different behavior patterns,both pro-social and anti-social. Such behavioralvariations among same-age youth tell us that regardlessof brain maturity, culture—something we canshape—is a powerful influence affecting teenagers’character and conduct. So even if the immature braindevelopment of young people is a factor in impulsivebehavior, our job as parents and teachers is not tosimply wait for the brain to mature, but rather to provideappropriate challenges that foster greater maturityof character and optimal functioning.<strong>Smart</strong> & <strong>Good</strong> <strong>High</strong> <strong>Schools</strong>2