Valuation of Biodiversity Benefits (OECD)

Valuation of Biodiversity Benefits (OECD)

Valuation of Biodiversity Benefits (OECD)

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

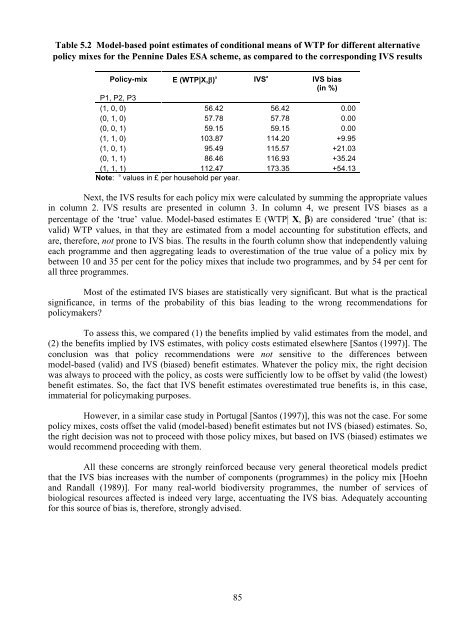

Table 5.2 Model-based point estimates <strong>of</strong> conditional means <strong>of</strong> WTP for different alternativepolicy mixes for the Pennine Dales ESA scheme, as compared to the corresponding IVS resultsPolicy-mix E (WTP|X,b) a IVS a IVS bias(in %)P1, P2, P3(1, 0, 0) 56.42 56.42 0.00(0, 1, 0) 57.78 57.78 0.00(0, 0, 1) 59.15 59.15 0.00(1, 1, 0) 103.87 114.20 +9.95(1, 0, 1) 95.49 115.57 +21.03(0, 1, 1) 86.46 116.93 +35.24(1, 1, 1) 112.47 173.35 +54.13Note: a values in £ per household per year.Next, the IVS results for each policy mix were calculated by summing the appropriate valuesin column 2. IVS results are presented in column 3. In column 4, we present IVS biases as apercentage <strong>of</strong> the ‘true’ value. Model-based estimates E (WTP| X, b) are considered ‘true’ (that is:valid) WTP values, in that they are estimated from a model accounting for substitution effects, andare, therefore, not prone to IVS bias. The results in the fourth column show that independently valuingeach programme and then aggregating leads to overestimation <strong>of</strong> the true value <strong>of</strong> a policy mix bybetween 10 and 35 per cent for the policy mixes that include two programmes, and by 54 per cent forall three programmes.Most <strong>of</strong> the estimated IVS biases are statistically very significant. But what is the practicalsignificance, in terms <strong>of</strong> the probability <strong>of</strong> this bias leading to the wrong recommendations forpolicymakers?To assess this, we compared (1) the benefits implied by valid estimates from the model, and(2) the benefits implied by IVS estimates, with policy costs estimated elsewhere [Santos (1997)]. Theconclusion was that policy recommendations were not sensitive to the differences betweenmodel-based (valid) and IVS (biased) benefit estimates. Whatever the policy mix, the right decisionwas always to proceed with the policy, as costs were sufficiently low to be <strong>of</strong>fset by valid (the lowest)benefit estimates. So, the fact that IVS benefit estimates overestimated true benefits is, in this case,immaterial for policymaking purposes.However, in a similar case study in Portugal [Santos (1997)], this was not the case. For somepolicy mixes, costs <strong>of</strong>fset the valid (model-based) benefit estimates but not IVS (biased) estimates. So,the right decision was not to proceed with those policy mixes, but based on IVS (biased) estimates wewould recommend proceeding with them.All these concerns are strongly reinforced because very general theoretical models predictthat the IVS bias increases with the number <strong>of</strong> components (programmes) in the policy mix [Hoehnand Randall (1989)]. For many real-world biodiversity programmes, the number <strong>of</strong> services <strong>of</strong>biological resources affected is indeed very large, accentuating the IVS bias. Adequately accountingfor this source <strong>of</strong> bias is, therefore, strongly advised.85