during full moon periods. Siganus sutor showed high site fidelity to <strong>spawning</strong> aggregation sites inKenya, though the more detailed telemetry data in Seychelles demonstrated that fidelity was notabsolute. Moreover, results from Seychelles also revealed turnover of S. sutor aggregations, inferredfrom aggregation site residency times being much shorter than aggregation duration (Chapter 6).Since this finding has implications for the estimation of aggregation size and therefore the impactsof fishing, further telemetry studies could be conducted on the Kenyan S. sutor aggregations todetermine if it is an aggregating dynamic common to this species.Rabbitfish (Siganidae) are schooling species with large home ranges (Fox and Bellwood 2011) bothof which pose challenges to research of their aggregation fisheries. The UVC results from Kenyaillustrated difficulties in distinguishing whether S. sutor were aggregating for <strong>spawning</strong> or wereforaging at aggregation sites. However, telemetry results from Seychelles indicated that S. sutor wereonly present at <strong>spawning</strong> aggregation sites during known <strong>spawning</strong> periods (Robinson et al. 2007;2011). Thus, a cautious interpretation of the Kenyan aggregations and study sites as being only for<strong>spawning</strong> is warranted.Regional similarities were found in the aggregation dynamics of the grouper E. fuscoguttatus(Serranidae), further confirming that this species typically forms transient <strong>spawning</strong> aggregationson outer reef slopes in relation to the new moon for 2-4 months each year (Chapter 6, 7, 8,9). However, acoustic telemetry studies and the existence of prior aggregation data in Seychellesyielded additional insights on aggregation dynamics in this species that should inform futureresearch and management in Kenya. Notably, sex-specific differences in male and female arrival andresidency times at aggregation sites in Seychelles highlight sex-specific variation in vulnerability toaggregation fishing, providing vital information for the design of fine-scale temporal managementmeasures (e.g. temporary fishery reserves or sales/catch restrictions). In addition, variability inthe spatial distribution of E. fuscoguttatus aggregations in Seychelles, due to habitat disturbance,provides a strong argument for larger protected areas that incorporate buffer zones.Similarities also exist between study locations in the socio-economic importance of S. sutoraggregation fisheries. Although catch rates of S. sutor on <strong>spawning</strong> aggregations increased 4-fold inKenya, aggregations were relatively short-lived and consequently yielded catches representing onlyaround 12% of the total annual catch. Therefore management of this species in Kenya needs toconsider the non-aggregation aspects of the fishery to control fishing mortality, a similar conclusionmade in Seychelles (Robinson et al. 2011) and further demonstrated in the modeling results (Chapter12). The importance of aggregation catch relative to the annual catch made on a population ispartly dependent on density-dependent catchability, i.e. the increase in population density andvulnerability to fishing that occurs with aggregation formation, as well as on aggregation durationand seasonality. Density change is less extreme in rabbitfish than groupers, while aggregations arealso much shorter in duration. Consequently, aggregation fishing is unlikely to be the primarysource of annual fishing mortality rates in rabbitfish (Robinson et al. 2011).Regional differences were seen in aggregation fisheries, such as in gear diversity. For example, whilePraslin Island fishers only use traps to target S. sutor aggregations, fishers in southern Kenya also usehook-and-line and anecdotal reports indicate that ring-nets are used (Chapter 3). Kenyan fishersalso use gillnets and illegal beach seines on S. sutor populations inshore. Gear diversity is known toincrease vulnerability in aggregation-based fisheries: the introduction of nets can result in a rapiddepletion of aggregation abundance (Chapter 11; Claro et al. 2009). These regional differencesfurther reinforce the need for a case-by-case approach to management.A fundamental constraint in addressing the management needs of <strong>spawning</strong> aggregation-basedfisheries is the difficulty in establishing aggregation status and its relationship to the populationas a whole. Both parameters require years of continued monitoring. In Kenya, E. fuscoguttatusaggregations were at least an order of magnitude smaller than some of those observed in Seychelles124

and some other Indo-Pacific locations (Johannes et al. 1999; Robinson et al. 2008b; Rhodes etal. 2012). Peak abundances in Kenya were most similar to those reported in Komodo (Indonesia)(Pet et al. 2005; Mangubhai et al. 2011), the Solomon Islands (Hamilton et al. 2012b) and PapuaNew Guinea (Hamilton et al. 2011) where aggregation fishing has been prevalent, including bythe live reef food fish trade. In Kenya, small aggregation sizes may not be exclusively a result offishing, but also low natural abundances in association with limited reef habitat, or a combinationof these factors. In Seychelles, this species also forms smaller, secondary aggregations in additionto large primary aggregations (Robinson et al. 2008b), a situation that may also exist in Kenya. Itis clear that aggregation size varies naturally on a range of scales, both within and between sites,thereby precluding inter-site comparisons and highlighting the need to monitor individual sites ata sufficient resolution to account for intra-site variability (Johannes et al. 1999).In the absence of status information for the majority of our study populations and <strong>spawning</strong>aggregations, the conceptual approach adopted by the research programme included thedevelopment of an indicator-based vulnerability framework that aims to identify fisheries ofconcern (Chapter 11). Based on our analyses, the vulnerability of our study populations to targetedaggregation fishing varied substantially. At one extreme, the targeting of a putative Epinepheluslanceolatus <strong>spawning</strong> aggregation off the southern tip of Unguja is likely to pose significant riskto the population from which it forms. At the other extreme, S. sutor is relatively productiveand populations appear able to sustain high levels of fishing mortality, even when aggregationsare targeted (Robinson et al. 2011; Grüss et al. in press). Regardless, fisheries management is stillrequired to prevent biological limits from being exceeded, as demonstrated by the no-take reserves(NTR) effects model. In between these extremes are the fisheries for Epinephelus fuscoguttatus andE. polyphekadion.There is considerable empirical and theoretical evidence (e.g. Jennings et al. 1998; Musick 1999;Dulvy et al. 2004) on the vulnerability to fishing conferred by the life history traits that weincluded in the intrinsic index of the vulnerability framework. However, knowledge of the socioeconomicfactors influencing exploitation rates is more limited for aggregation-based fisheries andhas generally been confined to qualitative expert reviews. Reviewing aggregation-based fisheriesglobally, Sadovy and Domeier (2005) conclude that populations may be sustained if aggregationsare subject to limited, subsistence levels of fishing. This implies that <strong>spawning</strong> aggregationscan be lightly exploited. If so, reference points or thresholds can be derived and used to guidemanagement actions, which is an important topic for future research. However, an understandingof the socio-economic drivers of fishing pressure and demand for aggregating species is critical iflimits on aggregation fishing are to be effectively managed. The socio-economic drivers of fishingpressure that we included as indicators in our vulnerability framework (fishers’ knowledge, marketdemand, etc, see Chapter 11) were also based on a review of the literature pertaining to bothaggregation fisheries and reef fisheries in general. Quantitative testing of these indicators and theoverall extrinsic index is warranted to better understand their relationship with rates of exploitationand aggregation status.The principal management measure we sought to evaluate was NTRs, given their widespread usein the WIO (IUCN 2004; McClanahan et al. 2009; Daw et al. 2011) and their potential use inpromoting resilience to climate change and other human impacts, such as fishing (Hughes et al.2003; McClanahan 20<strong>10</strong>). Our model for S. sutor and E. fuscoguttatus populations in Seychellesfound that NTRs sited on <strong>spawning</strong> sites can improve reproductive capacity, and also help normalizesex ratio in the protogynous grouper (Chapter 12). However, these benefits were relatively minor,especially if fishing effort is redistributed to non-<strong>spawning</strong> sites on reserve creation, which is themost realistic scenario (Valcic 2009). Therefore, NTRs for <strong>spawning</strong> aggregations have a role toplay in conserving populations but are only a part of the solution to overfishing. For example,reducing overall fishing effort on the population by even a small amount can produce a relativelylarge increase in reproductive capacity compared to NTR creation. Though not tested with the125

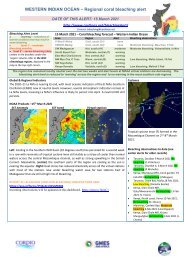

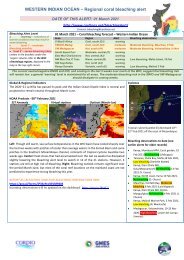

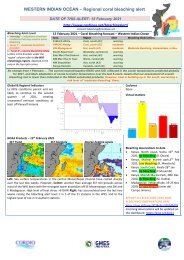

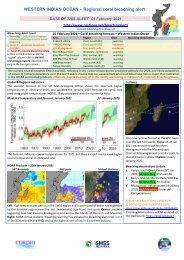

- Page 4:

The designation of geographical ent

- Page 9:

Chapter 1: IntroductionJan Robinson

- Page 12 and 13:

limited, subsistence levels of expl

- Page 14:

NTRs for spawning aggregations usin

- Page 17 and 18:

al. 2003). Verification may include

- Page 19 and 20:

a fraction of spawning sites are pr

- Page 21 and 22:

Chapter 3: Targeted fishing of the

- Page 23 and 24:

verifying spawning aggregations, we

- Page 25 and 26:

ecorded from inshore close to the c

- Page 27 and 28:

(a)(b)Fig. 3. Spatial patterns ofca

- Page 30 and 31:

pooled sizes of the three spawning

- Page 32 and 33:

found S. sutor contributed up to 44

- Page 34 and 35:

2011b). However, observations of fi

- Page 36 and 37:

MethodsTo identify seasonal and lun

- Page 38 and 39:

n=199Females GSI (mean ± SE)2.521.

- Page 40 and 41:

The estimate of size at maturity in

- Page 42 and 43:

This study was designed to verify S

- Page 44 and 45:

were selected. Fish selected for ta

- Page 46 and 47:

The number of traps increased on th

- Page 48 and 49:

Of the 9 tagged fish detected by re

- Page 50 and 51:

Fig. 7. Diel patterns ofdetection f

- Page 52 and 53:

Spawning aggregation site fidelity

- Page 54 and 55:

Chapter 6: Shoemaker spinefoot rabb

- Page 56 and 57:

anterior of the anus and below the

- Page 58 and 59:

A high percentage (80.8%) of depart

- Page 60 and 61:

arrivals and departures at these tw

- Page 62 and 63:

are typically applied for reef fish

- Page 64 and 65:

(a)(b)(c)Chapter 3, Figure 3. Spati

- Page 66 and 67:

(1)(2)(3)(4)(5)(6)Chapter 7, Table

- Page 68 and 69:

Chapter 12, Fig. 1 Fraction of fema

- Page 70 and 71:

Plates 8. Selected photographs from

- Page 72 and 73:

MethodsStudy sitesThe study area wa

- Page 74 and 75:

which shelved gently ( ca. 25 o ) t

- Page 76 and 77:

Fig. 4. Lunar periodicity in number

- Page 78 and 79:

Behaviour and appearanceDescription

- Page 80 and 81:

eported aggregations forming betwee

- Page 82 and 83: The sizes of E. fuscoguttatus aggre

- Page 84 and 85: Materials and methodsStudy area and

- Page 86 and 87: TL. All fish tagged were considered

- Page 88 and 89: Lunar timing of arrivals and depart

- Page 90 and 91: Fig. 8. The presence and absence of

- Page 92 and 93: aggregation fishing. This critical

- Page 94 and 95: Chapter 9: Persistence of grouper (

- Page 96 and 97: ResultsBetween 2003 and 2006, the c

- Page 98 and 99: Fig. 2. Mean (± standard error, SE

- Page 100 and 101: A few species (e.g. Epinephelus gut

- Page 102 and 103: (a)(b)Fig. 1. Map of (a) study site

- Page 104 and 105: Fig. 2. Number of E. lanceolatus ob

- Page 106 and 107: was having any impact on the popula

- Page 108 and 109: A spawning aggregation is said to o

- Page 110 and 111: Chapter 11: Evaluation of an indica

- Page 112 and 113: Table 1 Aggregation fisheries asses

- Page 114 and 115: the lists of Jennings et al. (1999)

- Page 116 and 117: with the more vulnerable labrids an

- Page 118 and 119: The remaining serranid populations

- Page 120 and 121: Spawning aggregation behaviour is c

- Page 122 and 123: tiger grouper, Mycteroperca tigris:

- Page 124 and 125: of protecting the normal residence

- Page 126 and 127: • Since grouper males are afforde

- Page 128 and 129: Fig. 2 Yield-per-recruit normalized

- Page 130 and 131: The approaches identified above are

- Page 134 and 135: model, many parameter estimates are

- Page 136 and 137: ReferencesAbunge C (2011) Managing

- Page 138 and 139: Cox DR (1972) Regression models and

- Page 140 and 141: Grüss A, Kaplan DM, Hart DR (2011b

- Page 142 and 143: Kaunda-Arara B, Rose GA (2004a) Eff

- Page 144: Newcomer RT, Taylor DH, Guttman SI

- Page 147 and 148: Sancho G, Petersen CW, Lobel PS (20

- Page 149 and 150: Appendix 1. QuestionnaireMASMA SPAW

- Page 151 and 152: 8. Spawning aggregation knowledgeUs

- Page 153 and 154: Example items KSh Furthest site Clo

- Page 155 and 156: Appendix II. Experimental testing o

- Page 157 and 158: Clove oil concentrationAt a concent

- Page 159 and 160: Appendix III. Application of acoust

- Page 161 and 162: 153