WIOMSA-CORDIO spawning book Full Doc 10 oct 13.pdf

WIOMSA-CORDIO spawning book Full Doc 10 oct 13.pdf

WIOMSA-CORDIO spawning book Full Doc 10 oct 13.pdf

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

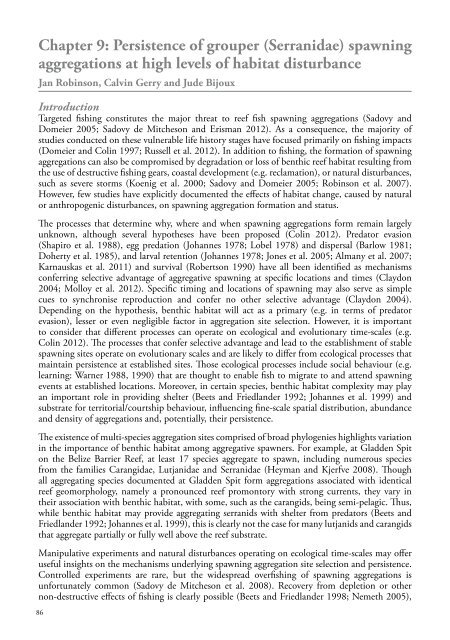

Chapter 9: Persistence of grouper (Serranidae) <strong>spawning</strong>aggregations at high levels of habitat disturbanceJan Robinson, Calvin Gerry and Jude BijouxIntroductionTargeted fishing constitutes the major threat to reef fish <strong>spawning</strong> aggregations (Sadovy andDomeier 2005; Sadovy de Mitcheson and Erisman 2012). As a consequence, the majority ofstudies conducted on these vulnerable life history stages have focused primarily on fishing impacts(Domeier and Colin 1997; Russell et al. 2012). In addition to fishing, the formation of <strong>spawning</strong>aggregations can also be compromised by degradation or loss of benthic reef habitat resulting fromthe use of destructive fishing gears, coastal development (e.g. reclamation), or natural disturbances,such as severe storms (Koenig et al. 2000; Sadovy and Domeier 2005; Robinson et al. 2007).However, few studies have explicitly documented the effects of habitat change, caused by naturalor anthropogenic disturbances, on <strong>spawning</strong> aggregation formation and status.The processes that determine why, where and when <strong>spawning</strong> aggregations form remain largelyunknown, although several hypotheses have been proposed (Colin 2012). Predator evasion(Shapiro et al. 1988), egg predation (Johannes 1978; Lobel 1978) and dispersal (Barlow 1981;Doherty et al. 1985), and larval retention (Johannes 1978; Jones et al. 2005; Almany et al. 2007;Karnauskas et al. 2011) and survival (Robertson 1990) have all been identified as mechanismsconferring selective advantage of aggregative <strong>spawning</strong> at specific locations and times (Claydon2004; Molloy et al. 2012). Specific timing and locations of <strong>spawning</strong> may also serve as simplecues to synchronise reproduction and confer no other selective advantage (Claydon 2004).Depending on the hypothesis, benthic habitat will act as a primary (e.g. in terms of predatorevasion), lesser or even negligible factor in aggregation site selection. However, it is importantto consider that different processes can operate on ecological and evolutionary time-scales (e.g.Colin 2012). The processes that confer selective advantage and lead to the establishment of stable<strong>spawning</strong> sites operate on evolutionary scales and are likely to differ from ecological processes thatmaintain persistence at established sites. Those ecological processes include social behaviour (e.g.learning: Warner 1988, 1990) that are thought to enable fish to migrate to and attend <strong>spawning</strong>events at established locations. Moreover, in certain species, benthic habitat complexity may playan important role in providing shelter (Beets and Friedlander 1992; Johannes et al. 1999) andsubstrate for territorial/courtship behaviour, influencing fine-scale spatial distribution, abundanceand density of aggregations and, potentially, their persistence.The existence of multi-species aggregation sites comprised of broad phylogenies highlights variationin the importance of benthic habitat among aggregative spawners. For example, at Gladden Spiton the Belize Barrier Reef, at least 17 species aggregate to spawn, including numerous speciesfrom the families Carangidae, Lutjanidae and Serranidae (Heyman and Kjerfve 2008). Thoughall aggregating species documented at Gladden Spit form aggregations associated with identicalreef geomorphology, namely a pronounced reef promontory with strong currents, they vary intheir association with benthic habitat, with some, such as the carangids, being semi-pelagic. Thus,while benthic habitat may provide aggregating serranids with shelter from predators (Beets andFriedlander 1992; Johannes et al. 1999), this is clearly not the case for many lutjanids and carangidsthat aggregate partially or fully well above the reef substrate.Manipulative experiments and natural disturbances operating on ecological time-scales may offeruseful insights on the mechanisms underlying <strong>spawning</strong> aggregation site selection and persistence.Controlled experiments are rare, but the widespread overfishing of <strong>spawning</strong> aggregations isunfortunately common (Sadovy de Mitcheson et al. 2008). Recovery from depletion or othernon-destructive effects of fishing is clearly possible (Beets and Friedlander 1998; Nemeth 2005),86