A COMPENDIUM OF SCALES for use in the SCHOLARSHIP OF TEACHING AND LEARNING

compscalesstl

compscalesstl

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

expected, though <strong>the</strong> LAI shared a stronger relationship with <strong>the</strong> PSRS than with <strong>the</strong> NIS.<br />

Fur<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong> collaborative bond subscale significantly contributed to <strong>the</strong> students' self-reported<br />

learn<strong>in</strong>g and actual course grade even after controll<strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> NIS and PSRS.<br />

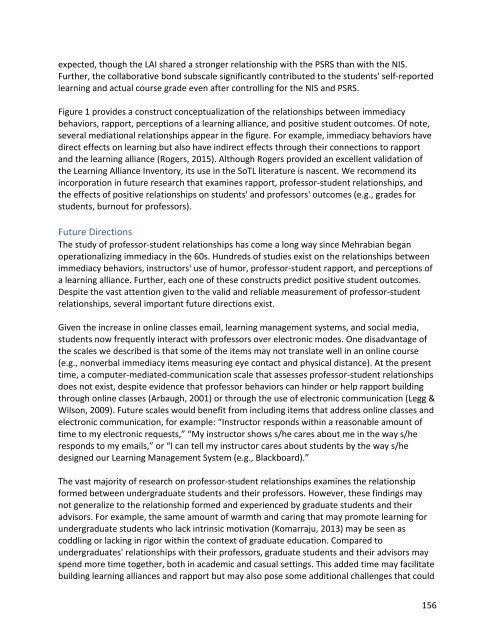

Figure 1 provides a construct conceptualization of <strong>the</strong> relationships between immediacy<br />

behaviors, rapport, perceptions of a learn<strong>in</strong>g alliance, and positive student outcomes. Of note,<br />

several mediational relationships appear <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> figure. For example, immediacy behaviors have<br />

direct effects on learn<strong>in</strong>g but also have <strong>in</strong>direct effects through <strong>the</strong>ir connections to rapport<br />

and <strong>the</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g alliance (Rogers, 2015). Although Rogers provided an excellent validation of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Learn<strong>in</strong>g Alliance Inventory, its <strong>use</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> SoTL literature is nascent. We recommend its<br />

<strong>in</strong>corporation <strong>in</strong> future research that exam<strong>in</strong>es rapport, professor-student relationships, and<br />

<strong>the</strong> effects of positive relationships on students' and professors' outcomes (e.g., grades <strong>for</strong><br />

students, burnout <strong>for</strong> professors).<br />

Future Directions<br />

The study of professor-student relationships has come a long way s<strong>in</strong>ce Mehrabian began<br />

operationaliz<strong>in</strong>g immediacy <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> 60s. Hundreds of studies exist on <strong>the</strong> relationships between<br />

immediacy behaviors, <strong>in</strong>structors' <strong>use</strong> of humor, professor-student rapport, and perceptions of<br />

a learn<strong>in</strong>g alliance. Fur<strong>the</strong>r, each one of <strong>the</strong>se constructs predict positive student outcomes.<br />

Despite <strong>the</strong> vast attention given to <strong>the</strong> valid and reliable measurement of professor-student<br />

relationships, several important future directions exist.<br />

Given <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> onl<strong>in</strong>e classes email, learn<strong>in</strong>g management systems, and social media,<br />

students now frequently <strong>in</strong>teract with professors over electronic modes. One disadvantage of<br />

<strong>the</strong> scales we described is that some of <strong>the</strong> items may not translate well <strong>in</strong> an onl<strong>in</strong>e course<br />

(e.g., nonverbal immediacy items measur<strong>in</strong>g eye contact and physical distance). At <strong>the</strong> present<br />

time, a computer-mediated-communication scale that assesses professor-student relationships<br />

does not exist, despite evidence that professor behaviors can h<strong>in</strong>der or help rapport build<strong>in</strong>g<br />

through onl<strong>in</strong>e classes (Arbaugh, 2001) or through <strong>the</strong> <strong>use</strong> of electronic communication (Legg &<br />

Wilson, 2009). Future scales would benefit from <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g items that address onl<strong>in</strong>e classes and<br />

electronic communication, <strong>for</strong> example: “Instructor responds with<strong>in</strong> a reasonable amount of<br />

time to my electronic requests,” “My <strong>in</strong>structor shows s/he cares about me <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> way s/he<br />

responds to my emails,” or “I can tell my <strong>in</strong>structor cares about students by <strong>the</strong> way s/he<br />

designed our Learn<strong>in</strong>g Management System (e.g., Blackboard).”<br />

The vast majority of research on professor-student relationships exam<strong>in</strong>es <strong>the</strong> relationship<br />

<strong>for</strong>med between undergraduate students and <strong>the</strong>ir professors. However, <strong>the</strong>se f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs may<br />

not generalize to <strong>the</strong> relationship <strong>for</strong>med and experienced by graduate students and <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

advisors. For example, <strong>the</strong> same amount of warmth and car<strong>in</strong>g that may promote learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong><br />

undergraduate students who lack <strong>in</strong>tr<strong>in</strong>sic motivation (Komarraju, 2013) may be seen as<br />

coddl<strong>in</strong>g or lack<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> rigor with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> context of graduate education. Compared to<br />

undergraduates' relationships with <strong>the</strong>ir professors, graduate students and <strong>the</strong>ir advisors may<br />

spend more time toge<strong>the</strong>r, both <strong>in</strong> academic and casual sett<strong>in</strong>gs. This added time may facilitate<br />

build<strong>in</strong>g learn<strong>in</strong>g alliances and rapport but may also pose some additional challenges that could<br />

156