- Page 1 and 2:

The Historiography of the Holocaust

- Page 3 and 4:

Also by Dan Stone BREEDING SUPERMAN

- Page 5 and 6:

Introduction, editorial matter, sel

- Page 7 and 8:

vi Contents 13. The German Churches

- Page 9 and 10:

viii Notes on the Contributors Tim

- Page 11 and 12:

x Notes on the Contributors Histori

- Page 13 and 14:

This page intentionally left blank

- Page 15 and 16:

2 Dan Stone of the past than has hi

- Page 17 and 18:

4 Dan Stone non-official company hi

- Page 19 and 20:

6 Dan Stone post-war European socie

- Page 21 and 22:

8 Dan Stone I. Deák, J.T. Gross an

- Page 23 and 24:

10 Oded Heilbronner policies of the

- Page 25 and 26:

12 Oded Heilbronner Here, some rese

- Page 27 and 28:

14 Oded Heilbronner whose worldview

- Page 29 and 30:

16 Oded Heilbronner focus’ from t

- Page 31 and 32:

18 Oded Heilbronner many sections w

- Page 33 and 34:

20 Oded Heilbronner H. Poetzsch, An

- Page 35 and 36:

22 Oded Heilbronner 29 See note 8 a

- Page 37 and 38:

2 Hitler and the Third Reich Jeremy

- Page 39 and 40:

26 Jeremy Noakes Hitler entered pol

- Page 41 and 42:

28 Jeremy Noakes issue for historia

- Page 43 and 44:

30 Jeremy Noakes French intellectua

- Page 45 and 46:

32 Jeremy Noakes accord Hitler litt

- Page 47 and 48:

34 Jeremy Noakes Hitlers in 1969, 6

- Page 49 and 50:

36 Jeremy Noakes followers. Kershaw

- Page 51 and 52:

38 Jeremy Noakes could govern other

- Page 53 and 54:

40 Jeremy Noakes stressed the signi

- Page 55 and 56:

42 Jeremy Noakes for the regime and

- Page 57 and 58:

44 Jeremy Noakes following any clea

- Page 59 and 60:

46 Jeremy Noakes Fascist-Nazi Polit

- Page 61 and 62:

48 Jeremy Noakes 48 E. Fraenkel, Th

- Page 63 and 64:

50 Jeremy Noakes Radicalisation and

- Page 65 and 66:

3 Expropriation and Expulsion Frank

- Page 67 and 68:

54 Frank Bajohr nameless bank accou

- Page 69 and 70:

56 Frank Bajohr state’. 17 Instea

- Page 71 and 72:

58 Frank Bajohr finance the German

- Page 73 and 74:

60 Frank Bajohr though these should

- Page 75 and 76:

62 Frank Bajohr in their totality.

- Page 77 and 78:

64 Frank Bajohr 26 G. Aly and C. Ge

- Page 79 and 80:

66 Tim Cole the following year in J

- Page 81 and 82:

68 Tim Cole Individual decisions in

- Page 83 and 84:

70 Tim Cole post-war period. The wo

- Page 85 and 86:

72 Tim Cole own destruction. They p

- Page 87 and 88:

74 Tim Cole Within such an approach

- Page 89 and 90:

76 Tim Cole was, Broszat argued,

- Page 91 and 92:

78 Tim Cole diseases, were unwillin

- Page 93 and 94:

80 Tim Cole and ideological reasons

- Page 95 and 96:

82 Tim Cole supervise convicts by p

- Page 97 and 98:

84 Tim Cole Notes 1 Cf., for exampl

- Page 99 and 100:

86 Tim Cole 60 Ibid., 346. 61 Ibid.

- Page 101 and 102:

5 War, Occupation and the Holocaust

- Page 103 and 104:

90 Dieter Pohl itself matters were

- Page 105 and 106:

92 Dieter Pohl exists on the role o

- Page 107 and 108:

94 Dieter Pohl gained new political

- Page 109 and 110:

96 Dieter Pohl inside (the post-war

- Page 111 and 112:

98 Dieter Pohl had been captured du

- Page 113 and 114:

100 Dieter Pohl and Majdanek, very

- Page 115 and 116:

102 Dieter Pohl decade. Tomasz Szar

- Page 117 and 118:

104 Dieter Pohl represented Polish

- Page 119 and 120:

106 Dieter Pohl Notes 1 Cf. Bibliog

- Page 121 and 122:

108 Dieter Pohl 28 Z. Mankowski, Mi

- Page 123 and 124:

110 Dieter Pohl 56 Cf. R. Hrabar, Z

- Page 125 and 126:

112 Dieter Pohl 81 K. Radziwonczyk,

- Page 127 and 128:

114 Dieter Pohl E. Kogon, H. Langbe

- Page 129 and 130:

116 Dieter Pohl Sicht der Täter un

- Page 131 and 132:

118 Dieter Pohl 151 Sharply critici

- Page 133 and 134:

6 Local Collaboration in the Holoca

- Page 135 and 136:

122 Martin Dean formations under Ge

- Page 137 and 138:

124 Martin Dean deep scars left on

- Page 139 and 140:

126 Martin Dean to take the lives o

- Page 141 and 142:

128 Martin Dean during the summer a

- Page 143 and 144:

130 Martin Dean one Jewish witness

- Page 145 and 146:

132 Martin Dean Jewish property rig

- Page 147 and 148:

134 Martin Dean and the development

- Page 149 and 150:

136 Martin Dean 18 See, for example

- Page 151 and 152:

138 Martin Dean Neue Studien zur na

- Page 153 and 154:

140 Martin Dean 77 See especially t

- Page 155 and 156:

142 Christopher Kobrak and Andrea H

- Page 157 and 158:

144 Christopher Kobrak and Andrea H

- Page 159 and 160: 146 Christopher Kobrak and Andrea H

- Page 161 and 162: 148 Christopher Kobrak and Andrea H

- Page 163 and 164: 150 Christopher Kobrak and Andrea H

- Page 165 and 166: 152 Christopher Kobrak and Andrea H

- Page 167 and 168: 154 Christopher Kobrak and Andrea H

- Page 169 and 170: 156 Christopher Kobrak and Andrea H

- Page 171 and 172: 158 Christopher Kobrak and Andrea H

- Page 173 and 174: 160 Christopher Kobrak and Andrea H

- Page 175 and 176: 162 Christopher Kobrak and Andrea H

- Page 177 and 178: 164 Christopher Kobrak and Andrea H

- Page 179 and 180: 166 Christopher Kobrak and Andrea H

- Page 181 and 182: 168 Christopher Kobrak and Andrea H

- Page 183 and 184: 170 Christopher Kobrak and Andrea H

- Page 185 and 186: 172 Christopher Kobrak and Andrea H

- Page 187 and 188: 174 Christopher R. Browning that Na

- Page 189 and 190: 176 Christopher R. Browning Jäckel

- Page 191 and 192: 178 Christopher R. Browning Hitler

- Page 193 and 194: 180 Christopher R. Browning from th

- Page 195 and 196: 182 Christopher R. Browning Solutio

- Page 197 and 198: 184 Christopher R. Browning the sca

- Page 199 and 200: 186 Christopher R. Browning the nee

- Page 201 and 202: 188 Christopher R. Browning into th

- Page 203 and 204: 190 Christopher R. Browning Jews (s

- Page 205 and 206: 192 Christopher R. Browning Entschl

- Page 207 and 208: 194 Christopher R. Browning (Berlin

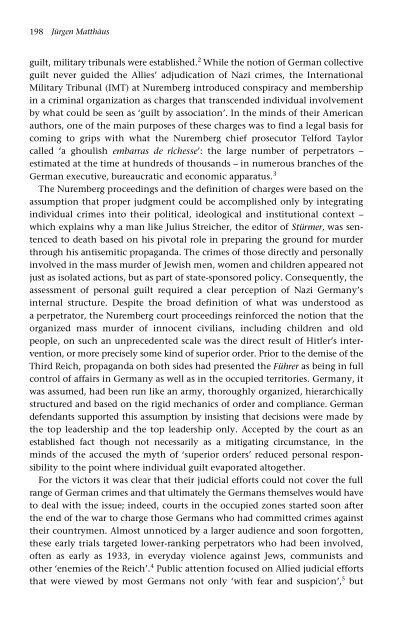

- Page 209: 196 Christopher R. Browning from Ki

- Page 213 and 214: 200 Jürgen Matthäus Cold War offe

- Page 215 and 216: 202 Jürgen Matthäus deviant trace

- Page 217 and 218: 204 Jürgen Matthäus bounds of the

- Page 219 and 220: 206 Jürgen Matthäus own way and n

- Page 221 and 222: 208 Jürgen Matthäus compliance fr

- Page 223 and 224: 210 Jürgen Matthäus perpetrators.

- Page 225 and 226: 212 Jürgen Matthäus for different

- Page 227 and 228: 214 Jürgen Matthäus by a Survivor

- Page 229 and 230: 10 The Topography of Genocide Andre

- Page 231 and 232: 218 Andrew Charlesworth So we are l

- Page 233 and 234: 220 Andrew Charlesworth Figure 2 Fi

- Page 235 and 236: 222 Andrew Charlesworth for killing

- Page 237 and 238: 224 Andrew Charlesworth a more like

- Page 239 and 240: Figure 7 226

- Page 241 and 242: 228 Andrew Charlesworth Figure 8 th

- Page 243 and 244: 230 Andrew Charlesworth Figure 9 Fi

- Page 245 and 246: 232 Andrew Charlesworth Figure 12 I

- Page 247 and 248: 234 Andrew Charlesworth Figure 14 p

- Page 249 and 250: 236 Andrew Charlesworth gas vans wi

- Page 251 and 252: 238 Andrew Charlesworth The connect

- Page 253 and 254: 240 Andrew Charlesworth Figure 19 F

- Page 255 and 256: 242 Andrew Charlesworth The ghettos

- Page 257 and 258: 244 Andrew Charlesworth Figure 23 o

- Page 259 and 260: 246 Andrew Charlesworth Figure 25 F

- Page 261 and 262:

248 Andrew Charlesworth what alread

- Page 263 and 264:

250 Andrew Charlesworth have the po

- Page 265 and 266:

252 Andrew Charlesworth 51 Intervie

- Page 267 and 268:

254 Tony Kushner documentaries. 3 T

- Page 269 and 270:

256 Tony Kushner Perceptions more t

- Page 271 and 272:

258 Tony Kushner comes back to Euro

- Page 273 and 274:

260 Tony Kushner War. Morse’s boo

- Page 275 and 276:

262 Tony Kushner It is significant

- Page 277 and 278:

264 Tony Kushner In the twelve mont

- Page 279 and 280:

266 Tony Kushner policy of both the

- Page 281 and 282:

268 Tony Kushner the lives of 10,00

- Page 283 and 284:

270 Tony Kushner 3 The film was dir

- Page 285 and 286:

272 Tony Kushner Doomed Jews’, Su

- Page 287 and 288:

274 Tony Kushner 69 Laqueur, The Te

- Page 289 and 290:

12 The Holocaust and the Soviet Uni

- Page 291 and 292:

278 John Klier Germans desired such

- Page 293 and 294:

280 John Klier The Jewish Anti-Fasc

- Page 295 and 296:

282 John Klier Investigations of ma

- Page 297 and 298:

284 John Klier The ear that hears,

- Page 299 and 300:

286 John Klier assignment included

- Page 301 and 302:

288 John Klier a much larger catego

- Page 303 and 304:

290 John Klier the end of the 1950s

- Page 305 and 306:

292 John Klier co-opt the site by i

- Page 307 and 308:

294 John Klier forced him to refuse

- Page 309 and 310:

13 The German Churches and the Holo

- Page 311 and 312:

298 Robert P. Ericksen and Susannah

- Page 313 and 314:

300 Robert P. Ericksen and Susannah

- Page 315 and 316:

302 Robert P. Ericksen and Susannah

- Page 317 and 318:

304 Robert P. Ericksen and Susannah

- Page 319 and 320:

306 Robert P. Ericksen and Susannah

- Page 321 and 322:

308 Robert P. Ericksen and Susannah

- Page 323 and 324:

310 Robert P. Ericksen and Susannah

- Page 325 and 326:

312 Robert P. Ericksen and Susannah

- Page 327 and 328:

314 Robert P. Ericksen and Susannah

- Page 329 and 330:

316 Robert P. Ericksen and Susannah

- Page 331 and 332:

318 Robert P. Ericksen and Susannah

- Page 333 and 334:

320 Dan Michman survivors or whole

- Page 335 and 336:

322 Dan Michman Terms and definitio

- Page 337 and 338:

324 Dan Michman Jewish history of t

- Page 339 and 340:

326 Dan Michman Jewish Councils, by

- Page 341 and 342:

328 Dan Michman (the occupied Czech

- Page 343 and 344:

330 Dan Michman is often imprecise

- Page 345 and 346:

332 Dan Michman their retrospective

- Page 347 and 348:

334 Dan Michman a variety of religi

- Page 349 and 350:

336 Dan Michman governments and wor

- Page 351 and 352:

338 Dan Michman Destruction of the

- Page 353 and 354:

340 Dan Michman J. Michman and T. L

- Page 355 and 356:

342 Robert Rozett to their deaths

- Page 357 and 358:

344 Robert Rozett in the anthologie

- Page 359 and 360:

346 Robert Rozett agree that armed

- Page 361 and 362:

348 Robert Rozett Armed resistance:

- Page 363 and 364:

350 Robert Rozett in advance for th

- Page 365 and 366:

352 Robert Rozett head of the Jewis

- Page 367 and 368:

354 Robert Rozett the Nazis, the fo

- Page 369 and 370:

356 Robert Rozett were saving other

- Page 371 and 372:

358 Robert Rozett More recent writi

- Page 373 and 374:

360 Robert Rozett 5 S. Friedländer

- Page 375 and 376:

362 Robert Rozett 50 R. Rozett, ‘

- Page 377 and 378:

16 Gender and the Family Lisa Pine

- Page 379 and 380:

366 Lisa Pine the Holocaust were to

- Page 381 and 382:

368 Lisa Pine holes, using needles

- Page 383 and 384:

370 Lisa Pine the universal Holocau

- Page 385 and 386:

372 Lisa Pine which tend to homogen

- Page 387 and 388:

374 Lisa Pine playgrounds in the gh

- Page 389 and 390:

376 Lisa Pine In the ghettos, many

- Page 391 and 392:

378 Lisa Pine vestiges of morale th

- Page 393 and 394:

380 Lisa Pine 18 Ibid., p. 48. 19 M

- Page 395 and 396:

382 Lisa Pine 79 Dwork, Children wi

- Page 397 and 398:

384 Ian Hancock advantage of this a

- Page 399 and 400:

386 Ian Hancock the only other popu

- Page 401 and 402:

388 Ian Hancock has) come from a cr

- Page 403 and 404:

390 Ian Hancock impurity’. The Me

- Page 405 and 406:

392 Ian Hancock The 1997 figure rep

- Page 407 and 408:

394 Ian Hancock was issued by the P

- Page 409 and 410:

396 Ian Hancock 30 S. Milton, ‘Na

- Page 411 and 412:

398 Donald Bloxham chapter, however

- Page 413 and 414:

400 Donald Bloxham now ‘allowed

- Page 415 and 416:

402 Donald Bloxham ‘intentionalis

- Page 417 and 418:

404 Donald Bloxham and kapos, one o

- Page 419 and 420:

406 Donald Bloxham Change or contin

- Page 421 and 422:

408 Donald Bloxham infamous anti-Je

- Page 423 and 424:

410 Donald Bloxham trial because th

- Page 425 and 426:

412 Donald Bloxham the social revol

- Page 427 and 428:

414 Donald Bloxham any inherently m

- Page 429 and 430:

416 Donald Bloxham 3 Osiel, Mass At

- Page 431 and 432:

418 Donald Bloxham ‘The Wheels of

- Page 433 and 434:

19 The Holocaust under Communism Th

- Page 435 and 436:

422 Thomas C. Fox the left - German

- Page 437 and 438:

424 Thomas C. Fox the hundreds of t

- Page 439 and 440:

426 Thomas C. Fox Jewish Historical

- Page 441 and 442:

428 Thomas C. Fox emphasizing Polis

- Page 443 and 444:

430 Thomas C. Fox with East Germany

- Page 445 and 446:

432 Thomas C. Fox amount of publica

- Page 447 and 448:

434 Thomas C. Fox organizations (wh

- Page 449 and 450:

436 Thomas C. Fox international con

- Page 451 and 452:

438 Thomas C. Fox Notes 1 See L. Lu

- Page 453 and 454:

20 Antisemitism and Holocaust Denia

- Page 455 and 456:

442 Florin Lobont Concurrently, Tis

- Page 457 and 458:

444 Florin Lobont Perhaps nothing c

- Page 459 and 460:

446 Florin Lobont experience of ind

- Page 461 and 462:

448 Florin Lobont But it was not on

- Page 463 and 464:

450 Florin Lobont ‘Scientific’

- Page 465 and 466:

452 Florin Lobont Jews. Just like A

- Page 467 and 468:

454 Florin Lobont Slovakia offers n

- Page 469 and 470:

456 Florin Lobont Jews or Zionism f

- Page 471 and 472:

458 Florin Lobont is ascribed to hi

- Page 473 and 474:

460 Florin Lobont Boris III while i

- Page 475 and 476:

462 Florin Lobont Tito’s authorit

- Page 477 and 478:

464 Florin Lobont unlike in the int

- Page 479 and 480:

466 Florin Lobont “radical reviva

- Page 481 and 482:

468 Florin Lobont 72 Tismaneanu, Fa

- Page 483 and 484:

470 Josh Cohen strains of neo-Kanti

- Page 485 and 486:

472 Josh Cohen After Auschwitz, the

- Page 487 and 488:

474 Josh Cohen economics’, Israel

- Page 489 and 490:

476 Josh Cohen overcoming the Holoc

- Page 491 and 492:

478 Josh Cohen and morally unassail

- Page 493 and 494:

480 Josh Cohen not identify the poi

- Page 495 and 496:

482 Josh Cohen abstractly, in the f

- Page 497 and 498:

484 Josh Cohen religion must perpet

- Page 499 and 500:

486 Josh Cohen Editions L’Aube, 1

- Page 501 and 502:

488 Zoë Waxman providing snapshots

- Page 503 and 504:

490 Zoë Waxman a commitment to rep

- Page 505 and 506:

492 Zoë Waxman a record of Jewish

- Page 507 and 508:

494 Zoë Waxman the survivors. In a

- Page 509 and 510:

496 Zoë Waxman With the Kristallna

- Page 511 and 512:

498 Zoë Waxman told. He must deliv

- Page 513 and 514:

500 Zoë Waxman struggle for a piec

- Page 515 and 516:

502 Zoë Waxman A statement such as

- Page 517 and 518:

504 Zoë Waxman society. The Britis

- Page 519 and 520:

506 Zoë Waxman 40 Six million is t

- Page 521 and 522:

23 Memory, Memorials and Museums Da

- Page 523 and 524:

510 Dan Stone Europe, as well as th

- Page 525 and 526:

512 Dan Stone enormous, socialist-r

- Page 527 and 528:

514 Dan Stone Ben Zvi’s To the Ch

- Page 529 and 530:

516 Dan Stone Peter Eisenman’s me

- Page 531 and 532:

518 Dan Stone ever-accelerating pre

- Page 533 and 534:

520 Dan Stone imply costly demands

- Page 535 and 536:

522 Dan Stone two distinct phases:

- Page 537 and 538:

524 Dan Stone memorial day were eve

- Page 539 and 540:

526 Dan Stone 5 Fritzsche, ‘The C

- Page 541 and 542:

528 Dan Stone (Frankfurt am Main: C

- Page 543 and 544:

530 Dan Stone S.D. Lavine, eds., Ex

- Page 545 and 546:

532 Dan Stone 73 Freed, ‘The Unit

- Page 547 and 548:

534 A. Dirk Moses moral evaluation,

- Page 549 and 550:

536 A. Dirk Moses imperialism, Axis

- Page 551 and 552:

538 A. Dirk Moses It is important t

- Page 553 and 554:

540 A. Dirk Moses killing not inten

- Page 555 and 556:

542 A. Dirk Moses Committee Draft w

- Page 557 and 558:

544 A. Dirk Moses Genocide research

- Page 559 and 560:

546 A. Dirk Moses be taken seriousl

- Page 561 and 562:

548 A. Dirk Moses Donald Bloxham em

- Page 563 and 564:

550 A. Dirk Moses campaign for the

- Page 565 and 566:

552 A. Dirk Moses 32 Ibid., p. 79.

- Page 567 and 568:

554 A. Dirk Moses Group, 1974); K.

- Page 569 and 570:

Index Aalders, Gerald, 57 Abel, The

- Page 571 and 572:

558 Index Bibo, Istvan, 431, 432 Bi

- Page 573 and 574:

560 Index Danzig-Westpreußen, 92,

- Page 575 and 576:

562 Index Giurescu, Dinu C., 457 Gl

- Page 577 and 578:

564 Index Jabès, Edmond, 478 Jäck

- Page 579 and 580:

566 Index Macedonia, 460 Mackensen,

- Page 581 and 582:

568 Index Phelps, Reginald, 26 Pika

- Page 583 and 584:

570 Index Shalev-Gerz, Esther, 514

- Page 585 and 586:

572 Index Union of Jewish Communiti