Experience is a solid walking stick...

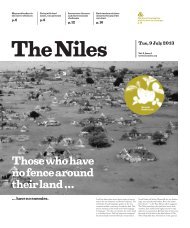

I don’t know where to start. I wish I had taken my wife. Who am I without my school certificates? These three remarks by refugees, scribbled into notebooks by The Niles correspondents, support the Sudanese proverb that ‘experience is a solid walking stick’. War, hunger and poverty have repeatedly forced both Sudanese and South Sudanese to flee their homes. Right now more than 4.5 million people are on the road in the two countries, like these passengers on a bus from Khartoum to Shendi. The fifth edition of The Niles documents their journeys, following their routes to neighbouring villages, fast-expanding cities or the other side of the globe, revealing diverse experiences with a recurring theme: When you leave home, the familiar is lost but the essential remains.

I don’t know where to start. I wish I had taken my wife. Who am I without my school certificates? These three remarks by refugees, scribbled into notebooks by The Niles correspondents, support the Sudanese proverb that ‘experience is a solid walking stick’. War, hunger and poverty have repeatedly forced both Sudanese and South Sudanese to flee their homes. Right now more than 4.5 million people are on the road in the two countries, like these passengers on a bus from Khartoum to Shendi. The fifth edition of The Niles documents their journeys, following their routes to neighbouring villages, fast-expanding cities or the other side of the globe, revealing diverse experiences with a recurring theme: When you leave home, the familiar is lost but the essential remains.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

The Niles 3<br />

On the run, again<br />

WAn estimated one in ten<br />

South Sudanese have been<br />

d<strong>is</strong>placed by recent fighting<br />

and for many it <strong>is</strong> not<br />

the first time.<br />

by Charlton Doki<br />

hen fighting spread across some South Sudanese states in late 2013 following<br />

a political struggle in Juba, people ran for their lives. It reminded many of how<br />

the region used to be in the decades of civil war before independence.<br />

During recent fighting the number of d<strong>is</strong>placed people rose to around 1.5<br />

million, or 10 percent of the population, as over a year of conflict erased early<br />

optim<strong>is</strong>m about South Sudan’s independence.<br />

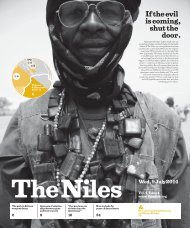

The power struggle, which started with a clash between presidential guards,<br />

revealed that the country was a tinderbox, awash with weapons and plagued by<br />

a militar<strong>is</strong>ed political culture. Tens of thousands of people have been killed in<br />

ensuing clashes. Figures from December 2014 show that more than 480,000 people<br />

have fled the country, while another million people have left their homes to try<br />

to find a safer place within South Sudan.<br />

Fighters show a “complete d<strong>is</strong>regard for international human rights and humanitarian<br />

law,” according to an open letter to President Barack Obama written by<br />

14 South Sudanese human rights groups, as well as Human Rights Watch, Amnesty<br />

International, Global Witness, and Humanity United. The groups called on the<br />

president to impose an arms embargo.<br />

Meanwhile, clashes between rebels and government forces continue, with<br />

outbreaks in Bentiu, Nasir, and Maban. Hundreds of people are estimated to have<br />

been killed, and the number of citizens on the move within the young country<br />

continues to climb.<br />

South Sudanese, who often fled into the bush with just the clothes on their back,<br />

have sought refuge at massive camps. Many, like Kakuma in Kenya, Pugnido in Ethiopia,<br />

and Adjumani in Uganda, were formed during what became Africa’s longest civil<br />

war between the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) and the government<br />

in Khartoum, which ended with the Comprehensive Peace Agreement in 2005.<br />

These sprawling camp settlements, with their makeshift abodes and rudimentary<br />

health services run by international organ<strong>is</strong>ations like Save the Children, Médecins<br />

Sans Frontières, and the American Refugee Committee, have expanded fast. Pugnido<br />

in Ethiopia’s Gambella region <strong>is</strong> the biggest, forming a temporary home to some<br />

257,887 people. Some have developed into semi-permanent settlements dating from<br />

the last civil war.<br />

And Khartoum has become the final destination of many South Sudanese,<br />

often taken in by extended family networks. According to United Nations data,<br />

neighbouring Ethiopia, especially the Gambella region, Uganda, Kenya, and Sudan,<br />

have all become home to more than 600,000 refugees. They mostly reside in camps<br />

near the border, often with insufficient food, education, and healthcare. Of these,<br />

Ethiopia hosts the highest number of South Sudanese refugees.<br />

And the fighting never ends. Many refugees returned to South Sudan to<br />

vote for independence or to settle in the new state, only to move again, as violence<br />

spiralled afresh.<br />

These days, few of the d<strong>is</strong>placed people can imagine a swift return home.<br />

Extended peace talks in Add<strong>is</strong> Ababa between representatives of South Sudanese<br />

President Salva Kiir and rebel leader and former Vice-President Riek Machar<br />

have failed to halt the violence. A string of ceasefires were broken within days.<br />

Shortly after clashes broke out in December 2013, Kiir blamed h<strong>is</strong> rival Machar<br />

for plotting a coup, although no evidence was found. But army commanders rebelled<br />

in three states and, over the following year, violence affected a number of other<br />

states, including attacks along ethnic lines between the Nuer and Dinka groups.<br />

Crude oil production, which makes up more than 90 percent of South Sudan<br />

government revenue, has fallen by at least a third during the conflict, as the army<br />

fought rebels in two key oil-producing areas.<br />

The United Nations estimates that thousands more South Sudanese are likely<br />

to seek refuge over the border in Sudan, potentially doubling the size of the South<br />

Sudanese refugee community there.<br />

Despite the ongoing conflict, South Sudan has also taken in refugees from<br />

neighbouring countries. Last year, it became home to some 245,003 reg<strong>is</strong>tered<br />

refugees, mostly from Sudan, according to a recent update from the United Nations’<br />

refugee agency (UNHCR). Th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> part of a longer h<strong>is</strong>tory showing South Sudan<br />

(previously Southern Sudan) has long been both a source and a receiver of refugees.<br />

The area witnessed its most significant influx of refugees following the overthrow<br />

of former Ugandan leader Idi Amin Dada in 1979, when Ugandans sought shelter<br />

from the bloodshed. By 1982 the number of Ugandan refugees swelled to around<br />

a quarter of a million as Amin’s supporters launched a guerrilla war in the northwestern<br />

part of the country in response to abuses committed by the Ugandan<br />

National Liberation Army.<br />

In 1984-5, the UNHCR helped some of the Ugandan refugees to return home.<br />

At th<strong>is</strong> time, Southern Sudan was relatively peaceful and Ugandan refugees settled.<br />

More than 200,000 Ugandan refugees opted to remain on the eastern bank of the<br />

Nile. “Most of the Ugandans had establ<strong>is</strong>hed relatively affluent livelihoods in Sudan<br />

(Southern Sudan), and were unwilling to return to Uganda with all the political<br />

uncertainties,” Jozef Merkx wrote in a UNHCR working paper.<br />

Many stayed in Southern Sudan until rebels led by Yoweri Museveni took<br />

power in Kampala in January 1986, improving security in Uganda. That, combined<br />

with intensified fighting in Southern Sudan in 1988-89, prompted many Ugandan<br />

refugees to return home, joined by thousands of Southern Sudanese.<br />

Ties between populations in Uganda and Southern Sudan date from earlier<br />

generations, in particular the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s, partly due to the absence<br />

of Sudan-Ugandan border controls at the time. By the 1940s thousands of Southern<br />

Sudanese had migrated to Uganda to work in the cotton and sugar industries as<br />

Uganda’s economy grew. The movement of these early economic migrants helped<br />

tighten relations between tribes on either side of the border, including the Madi<br />

and Kakwa.<br />

“The relations establ<strong>is</strong>hed during th<strong>is</strong> migration later enabled Southern<br />

Sudanese to settle in northern Uganda,” the UNHCR wrote in its report, entitled<br />

Refugee identities and relief in an African borderland: a study of northern<br />

Uganda and Southern Sudan, adding that they arrived “among their kin when<br />

they had to flee from the civil war in Southern Sudan.” Th<strong>is</strong> trend of social<br />

upheaval continues to th<strong>is</strong> day, and, observers warn, looks set to endure in the<br />

foreseeable future.<br />

A single one among millions of Sudanese<br />

and South Sudanese refugees.<br />

theniles_enar_20150327.indd 3<br />

2015/3/31 1:50 PM