Undergrad_Book_16-18_Pge_View_Print_no print marks_compressed

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Undergrad</strong>uate Research at UMass Dartmouth<br />

171<br />

Since the closing of American factories in the late<br />

1970s, post-industrial ruins have appeared in many<br />

parts of the United States. Whether left abandoned<br />

or transformed into new uses, the post-industrial<br />

building is a prevalent force on the Northeastern<br />

American setting. Accordingly, these buildings<br />

(especially their rui<strong>no</strong>us shells), have been popular<br />

subjects of both art and art historical research and<br />

are particularly of interest to photographers. Having<br />

read a vast body of literature on the American<br />

post-industrial city, I learned that, unfortunately,<br />

many of these urban contexts end up remaining in<br />

ruins, a problem particularly common in Detroit.<br />

Foreign tourists come to see the abandoned factories,<br />

forcing the city to remain in disrepair with a<br />

low quality of life for its citizens. What is the history<br />

of the fetishization or the neglect of the industrial<br />

ruin in the New England region? How far back does<br />

this history go? What can we learn from this history?<br />

How can this historical k<strong>no</strong>wledge allow us to come<br />

up with better ways of representing these cities and<br />

even providing remedies for them?<br />

character in photography is also directly tied to their<br />

complicated relationship to American history. The<br />

industrial factory and its corresponding neighborhood<br />

was at once a symbol for American power and<br />

wealth as well as a reflection of the flawed class<br />

system that forced many into difficult labor. The<br />

period of prosperity in which factories were prominent<br />

was also a time of intense race and gender<br />

boundaries, and reflections on the post-industrial<br />

building are innately tied to the society created by<br />

powerful class borders. Americans’ relationship<br />

to the post-industrial ruin is inherently entwined<br />

with our complicated feelings about our difficult<br />

past. However, ruins are fundamentally ambiguous;<br />

the empty spaces can be <strong>no</strong>stalgic, prophetic, or<br />

escapist, so the meaning heavily relies on artists’<br />

intentions and viewer expectations.<br />

In fall 2015 I received a grant from the OUR to investigate<br />

the ways in which the post-industrial landscapes<br />

of the Northeast were depicted in the work of<br />

late-twentieth century artists. My research analyzed<br />

Northeastern American post-industrial ruins in the<br />

work of six artists from four perspectives: ruins as<br />

prophetic, ruins as <strong>no</strong>stalgic, ruins as disappointment,<br />

and ruins as problematic. The ambiguity of the<br />

ruin allows these vastly different lenses to color the<br />

interpretations of ruins photography. Their complex<br />

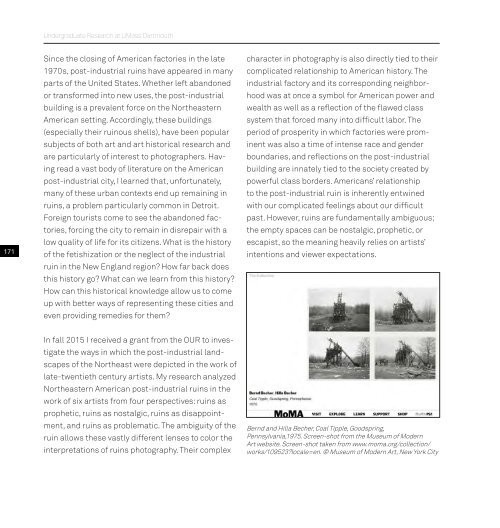

Bernd and Hilla Becher, Coal Tipple, Goodspring,<br />

Pennsylvania,1975. Screen-shot from the Museum of Modern<br />

Art website. Screen-shot taken from www.moma.org/collection/<br />

works/109523?locale=en. © Museum of Modern Art, New York City